Where is Barakhamba Cemetery in Delhi? Even those who are intimately familiar with Delhi will find it difficult to answer that question. Etymologically, the word monument means a burial place or tomb, erected in memoriam. Therefore, Barakhamba Cemetery should be a monument, as it indeed is. Not only is it a monument, it is a national monument. The responsibility for protecting it vests with Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Except that, unfortunately, ASI has lost that monument. Reminds you of that quote from Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. “To lose one parent, Mr. Worthing, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.” Lady Bracknell would have shuddered. ASI’s monumental performance transcends both misfortune and carelessness. ASI has lost 24 monuments. They are untraceable.

Let me backtrack a bit and quote from 324th report, submitted to Parliament on June 15, 2022. This is the report of Rajya Sabha’s department-related Standing Committee on transport, tourism and culture. This focused on untraceable monuments. “The primary mandate of ministry of culture is preservation and conservation of ancient cultural heritage and promotion of tangible and intangible art and culture. The ministry manages all the Centrally Protected Monuments (CPMs) of national importance, through the Archaeological Survey of India. The ministry, in its written reply furnished to the Committee, informed that there are 3,693 Centrally Protected Monuments and 4,508 State Protected Monuments in the country.” Given India’s geographical expanse, this figure on protected monuments is a small number, even more so if we focus only on the centrally protected ones. But despite that small number of centrally protected ones, we lost monuments. They became untraceable. To continue with another quote from the 324th report, “The ministry, in its background note on the subject, stated that the CAG in its 2013 Report on “Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities” submitted to Parliament on 23.8.2013 had reported that 92 monuments are missing. However, vigorous efforts to locate/identify the reportedly untraceable monuments based on verification of old records, revenue maps and referring published reports were carried out by the respective field offices of Archaeological Survey of India. The exercise gave fruitful results and many monuments were traced out.” A monument vanishes and is rediscovered.

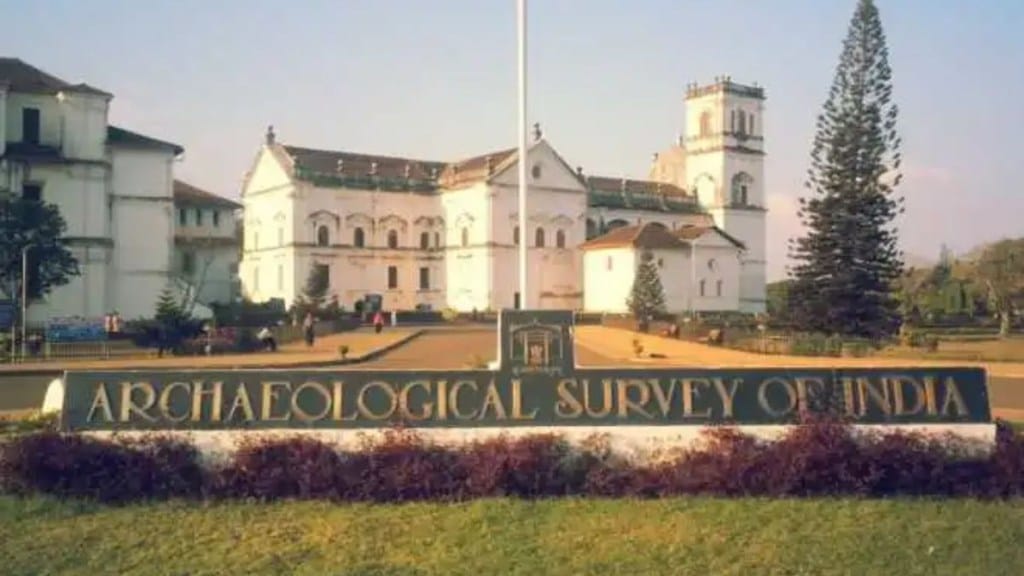

But, there are 24 that have still not been rediscovered. (There may be more that are untraceable, but this is the official figure.) One of these is Barakhamba Cemetery in Delhi. Barakhamba simply means twelve pillars, and we will promptly think of Barakhamba Road. Barakhamba Road is evidently named after the house, with twelve pillars, of a 14th century nobleman from the Tughlaq era. If this identification is correct, those antecedents of Barakhamba Road have long disappeared. Barakhamba Cemetery is different. That seems to have been in the Nizamuddin area. In the first decade of the 20th century, Maulvi Zafar Hasan told us (in his report) this cemetery, also from the Afghan era, had become the executive engineer’s office. Subsequently, it became part of Ghalib Park or the nearby Lal Mahal. Hence, we will probably never be able to find it, despite ASI’s hopes of using modern scientific tools to rediscover them. Some monuments are lost to urbanization, others submerged. If they are completely destroyed, what hope is there? ASI was set up in 1861. Post-Independence, how do we decide what is a national monument? Do we simply carry forward historical and arbitrary decisions? Shouldn’t we de-notify those for which there is no hope? Is ASI equipped to protect national monuments, or does it hinder the process?

Among such missing monuments, there are Kos Minars in Mujesar (Faridabad) and Shahabad (Kurukshetra). Kos Minars marked out the distance of one krosha (roughly 2 miles) and proliferated along Grand Trunk Road, thanks to Sher Shah Suri. Some are in excellent states of preservation in UP, Rajasthan, Haryana and Punjab, and even in Pakistan. But not those in Mujesar and Shahabad. Indeed, out of 49 Kos Minars in Haryana, only eight remain. Others have been swallowed up by development, including those in Mujesar and Shahabad. The land on which the Mujesar one stood, was acquired by Haryana government in 1983, and handed over to a company that demolished the Kos Minar.

Similarly, the last time the Shahabad one was seen was in 1955. Haryana Urban Development Authority (HUDA) acquired the land and developed it, the Kos Minar vanishing in the process. If Kos Minars are along GT Road and if national highways expand and develop along GT Road, won’t they inevitably disappear? Other than the rhetorical questions above, what exactly is a monument? The word tends to suggest a large structure. In the list of 24 untraceable ones, why have a “tablet on treasury building” in Varanasi? Modern tablets have limited life. But traditional tablets can’t last for an inordinately long time period either. That 324th report gives us a lot to think about and I have skipped the recommendations, several of which are about ASI’s style of functioning and its human and financial resources. To quote one sentence, “If even monuments in the Capital city cannot be maintained properly, it does not bode well for monuments in remote places in the country.”

Author is Chairman, EAC-PM

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.