Prachi Priya

Aniruddha Ghosh

While India’s recent disinflationary trend has given some comfort to RBI, it has caught the central bank by surprise. In its December monetary policy meeting, RBI kept policy rates unchanged, but revised down its inflation projection for H2FY19 to 2.7-3.2% from an earlier projection of 3.9-4.5%, citing unexpected softening of food prices and fall in crude oil prices.

From a monetary policy (inflation targeting) perspective, this is good news, but the bad news is that the disinflation has been primarily driven by softer food prices. Headline inflation (April-November) for FY19 averaged 4%, while food inflation during the same period averaged 0.9%. It is worth noting that, on a sequential basis, food price deflation (negative growth) has continued since April this year. Even on a year-on-year basis, food prices de-grew in October-November, led mostly by softer vegetable, pulses, cereal and sugar prices. In November, food inflation dipped to an all-time low of (-)2.6% year-on-year.

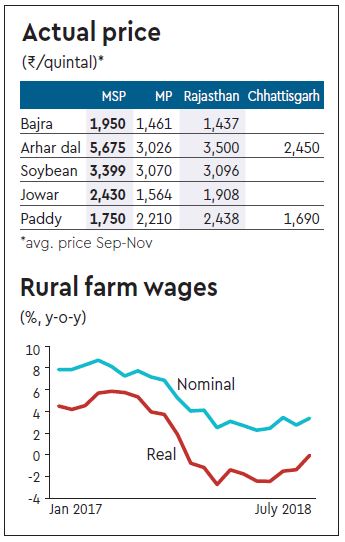

The government, on its part, announced an increase in minimum support prices (MSP) for kharif crop for 2018-19. The MSP increased by an average of 24% for 2018-19, compared to an average of 4.5% between FY14 and FY18. Estimates suggest that only a fraction (nearly 6%) of the aggregate produce of agricultural commodities is procured under the state and central procurement system. Despite the hikes and limited procurement reach, evidence from Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh shows that the actual sale price for major commodities has remained below the MSP announced for major kharif crops. Not to forget, agrarian distress has been hypothesised as one of the key reasons for the loss of the ruling party in state elections in these three states. Officially available data from the Directorate of Marketing and Inspection, Department of Agriculture, shows that actual wholesale prices in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan for major crops like bajra, arhar, soybean and jowar have been less than the MSP announced. Only for paddy, the prices were higher than MSP in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. In Chhattisgarh, even for paddy, the actual prices were lower than MSP (see table).

Also, the trend in rural farm wage growth has been disappointing. Both in nominal and real terms, farm wages have been on a decline. Nominal wages have fallen by more than 4 percentage points in 2018 compared to 2017, while in real terms farm wages have been de-growing since November last year.

All in all, declining inflation at the cost of lower food prices combined with farm distress is not a good sign for an economy that wishes to see sustainable economic growth of at least 8-9%. Rural consumption accounts for 55% of overall consumption and is a major driver of economic growth. Squeezing purchasing power of the rural economy can drag down growth further. Former chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian recently pointed out that agrarian distress was one of the biggest challenges faced by India, and will be a big-ticket item in most election manifestos heading into 2019. The first evidence of this is being seen in the form of promises of state-loan waivers for agricultural farmers.

But loan waivers are not the solution to the current agrarian distress. Loan waivers do not cover loans from non-institutional sources like moneylenders, which are arguably the largest credit providers in the agricultural sector. As per 70th round of NSSO survey, in India about 52% of agricultural households are indebted, and 82% of all the indebted households are marginal or small farmers. The average amount of outstanding loan per agricultural household is Rs 47,000. Almost 40% of the outstanding loans of India’s agriculture households are from non-institutional sources like moneylenders, traders, family, employers, etc. What’s interesting to note is that the share of institutional sources decreases with the size of land possessed. So, for marginal farmers (less than 1 hectare of land), the share of institutional sources in outstanding loan is 38% compared to large farmers (more than 10 hectares land) where the share of institutional sources is 79%. And for farmers with less than 0.01 hectare of land, only about 15% of the outstanding loan is from institutional sources.

Thus, loan waivers in itself benefit only a section of farmers who possess bigger land pieces. Moreover, studies find that farmers often use the saved money from loan waivers for consumption purposes rather than agriculture investment activity. Also, default on loans and grant of loan waivers decrease the ability of a farmer to apply for a loan again. A dispassionate analysis of loan waivers would suggest how loan waivers increase fiscal deficit, impact loan repayment behaviour, combined with worsening of balance sheets of lending institutions.

The CAG report on the UPA’s Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme (ADWDRS 2008) raised serious questions on its implementation, its omissions and commissions, monitoring of loans and refinancing. It is hard to argue against the immediate and emotive relief that waivers have on financially stressed farmers, but the long-term and contagious effects on the economy are strong enough to be ignored. In light of these observations, one would expect the political leadership to have a more holistic view on this sector rather than a limited and, often, ill-conceived and implemented panacea.

Therefore, this trio of low inflation, robust real rural wages, and a sustainable and structurally strong and growing agricultural economy presents an important challenge for all the stakeholders. With 2019 general elections round the corner, the pressure will be on the government to deliver on its promise of a ‘productive, scientific and rewarding’ agriculture as per its manifesto. It’s well-researched that investing a rupee in agriculture infrastructure like warehouses, canals, marketing and technology will be more productive in the long run than doling out of loan waivers to farmers. Short-term fixes will only worsen the situation further.

(Priya is a Mumbai-based economist. Ghosh is a PhD candidate in Economics at Johns Hopkins University, US)