At 95, Warren Buffett is retiring for the third and presumably final time.

On December 31st, he’ll step down as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, America’s ninth-most-valuable company worth over $1 trillion. As he hands over the reins to Gregory Abel, investors worldwide are asking: What made the Oracle of Omaha so extraordinary?

Here’s a number that will make your jaw drop: Buffett’s personal stake in Berkshire grew to be worth over $125 billion, even after donating tens of billions to charity. No one else has ever built such an investment fortune from scratch.

Let’s dive in.

The man who made investing look boring (and made billions doing it)

Here’s the thing about Warren Buffett: He became one of the richest people on Earth by doing something spectacularly mundane. He wasn’t inventing groundbreaking technology or creating viral social media platforms. He was simply buying stocks and whole companies and holding them. That’s it.

But here’s where it gets interesting.

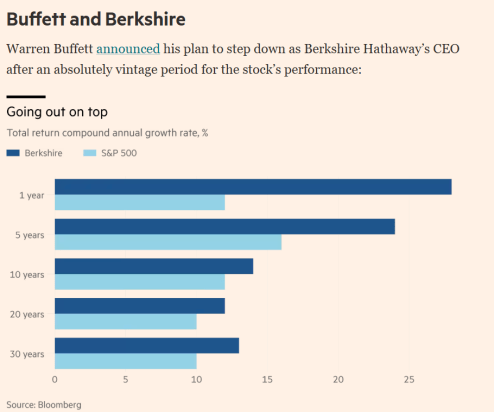

Since taking control of Berkshire Hathaway in the 1960s, the company’s shares have generated returns that dwarf the S&P 500. We’re talking about beating the market by a few percentage points every single year for decades.

Between 1964 and 2024, Berkshire Hathaway’s stock compounded at 19.9% annually, translating into a staggering total return of 5,502,284%. In comparison, the S&P 500, including dividends, delivered 10.4% annualised returns over the same period, amounting to a total return of 39,054%.

Read that again. The same $10,000. A 20x difference.

This is what makes Buffett’s achievement so staggering. It wasn’t about hitting home runs every year. It was about consistently hitting singles and doubles, year after year, decade after decade, and letting compound interest work its slow, inexorable magic.

But how did he actually pull this off? Well, it comes down to a business structure that’s absolutely genius and completely unique.

The insurance money printer

In 1967, Berkshire bought National Indemnity, a Nebraska-based insurer. This wasn’t just another acquisition. It was the foundation of Buffett’s empire.

Here’s how the magic works: Insurance companies collect premiums from policyholders before they pay out claims. When run profitably, insurers can invest those premiums and pocket the returns. This is called “float.”

Most insurers park this float in boring, safe bonds. But Buffett? He invested half of Berkshire’s insurance assets in a concentrated portfolio of stocks. Think about this for a moment. Buffett essentially created a self-financing investment vehicle. Insurance customers don’t make margin calls. They don’t panic when markets crash. They just keep paying premiums, giving Buffett an endless supply of low-cost capital to deploy.

The scale is staggering. Berkshire is now America’s second-largest property and casualty insurer, with nearly $700 billion in tradable stocks, bonds, and cash. BNSF, one of America’s four major railroads, was initially owned by National Indemnity. Even Berkshire’s quarter-stake in Occidental Petroleum is housed within the insurance operation.

This structure gave Buffett something other investors could only dream of: patient capital that never demanded immediate returns. While other investors faced margin calls and redemption pressures during market crashes, Buffett could sit tight or better yet, buy more at bargain prices.

The moat obsession

Now let’s talk about what Buffett actually bought with all this capital.

Buffett loves talking about “moats” – competitive advantages that allow businesses to consistently earn returns above their cost of capital. His portfolio tells the story beautifully. Look at Berkshire’s top five holdings:

- Apple (21% of portfolio) – Worth $65 billion. Consumer loyalty that borders on religious devotion.

- American Express (17.8%) – Worth $58 billion. Network effects and brand power in financial services. Bought in the 1960s during a scandal when everyone else was selling.

- Bank of America (9.8%) – Worth $32 billion. Regulatory advantages and scale.

- Coca-Cola (9.3%) – Worth $28 billion. Bought in the 1980s for around $1.3 billion. Global brand recognition and distribution.

- Chevron (5.9%) – Natural resource control and infrastructure.

Notice a pattern? These aren’t hot tech startups or speculative growth plays. They’re established companies with massive competitive advantages, what Buffett calls “businesses so wonderful that an idiot can run them.”

The Apple investment perfectly illustrates Buffett’s evolution. Once focused on “value” stocks trading below book value, he learned to pay fair prices for exceptional businesses. At its peak, Apple represented roughly 40% of Berkshire’s entire equity portfolio, worth nearly $200 billion. Buffett himself jokingly thanked Apple CEO Tim Cook for “making Berkshire shareholders more money than he ever has.”

But here’s what’s fascinating: Buffett didn’t need to be right all the time. He just needed to be right more often than wrong, and when he was right, he held on for decades. When American Express faced a scandal in the 1960s and the stock tanked, most investors fled. Buffett bought more. That position is now worth $58 billion from an initial investment of just a few million.

The reputation multiplier

But there’s something else academics miss: Buffett’s genius for public relations may rival his genius for investing.

Berkshire’s beta (volatility relative to the market) sits below 1, despite using leverage. Why? Because investors trust Buffett so completely that they don’t panic during rough patches. This trust allowed him to use leverage safely for decades, something most investors simply cannot do without risking margin calls and forced selling.

Buffett cultivated this reputation meticulously. His annual shareholder letters became must-reads, filled with memorable wisdom delivered in plain English:

- “Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.”

- “It’s only when the tide goes out that you learn who’s been swimming naked.”

- “Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.”

His annual meetings evolved into the “Woodstock of Capitalism,” attracting tens of thousands of devoted followers. He transformed a boring corporate requirement into a pilgrimage where people bought See’s Candies, Nebraska Furniture Mart sofas, and GEICO insurance just to feel closer to the master.

When financial crises hit, Buffett became America’s modern-day J.P. Morgan, infusing capital into troubled firms like Goldman Sachs during 2008, essentially putting his imprimatur on their solvency. His investments calmed panicked markets because everyone trusted his judgment.

This reputation had tangible value. It attracted acquisition candidates who wanted Berkshire as a “forever home” for their family businesses. It gave Buffett access to deals others couldn’t get. It kept shareholders patient through inevitable periods of underperformance.

The $400 billion warning shot

Now here’s where the story gets really interesting.

As Buffett prepares to retire, Berkshire is sitting on nearly $400 billion in cash and short-term Treasuries. That’s more than the market caps of companies like Netflix, Coca-Cola, or Intel. And it’s sending a clear message to anyone paying attention.

Buffett has been here before. In 1968, during the growth stock boom, he closed his investment partnership and returned money to partners, saying he was “not attuned to this market environment.” The market subsequently delivered some of its worst inflation-adjusted returns through 1974. In 1999, during the dot-com bubble, he was called a laggard for avoiding tech stocks. The NASDAQ then crashed 80% by 2002.

Today, with the S&P 500 trading near record valuations and “Magnificent Seven” AI stocks commanding price-to-earnings ratios above 30, Buffett is once again raising cash. He’s been building this cash pile since the bull market began in 2023, growing it from $100 billion to nearly $400 billion. He’s not predicting an immediate crash. He’s simply saying that risk-free Treasuries yielding 3.6% look more attractive than most stocks at current prices.

Think about what this means: Buffett, who built his fortune by being greedy when others were fearful, is now fearful. He’s saying, “I’d rather earn a guaranteed 3.6% than chase stocks at these valuations.” That’s a man who’s seen this movie before and knows how it ends.

He’s been selling Apple aggressively since late 2023. The position that once represented 40% of the portfolio and was worth nearly $200 billion is now down to just $65 billion. He’s also trimmed or completely exited Bank of America and many other holdings. Meanwhile, he’s mostly avoided the AI craze, though the company did recently take a small stake in Alphabet.

With his track record of being right about overvaluation in 1968 and 1999, ignoring this signal would be financial malpractice. His past warnings preserved capital for those who listened and allowed them to deploy it when bargains emerged. Those who didn’t learned expensive lessons.

What makes buffett truly exceptional

Strip away the billions, and what made Buffett genuinely exceptional wasn’t just his stock-picking ability. Plenty of investors have had great years or even great decades.

What sets Buffett apart is longevity. He operated at the top of his game for nearly three-quarters of a century.

Here’s a mind-bending way to think about it: Imagine being selected for an All-Star team in any profession, every single year, for 60 consecutive years. That’s Buffett’s investment career. From the mid-1960s through the mid-2020s, if you’d asked serious students of finance to vote for an investing All-Star team at any moment, Buffett would’ve made every ballot, every year.

His early partnership, started when he was just 25, produced extraordinary returns over nearly 15 years, compounding at roughly 30% annually. Then Berkshire took over, continuing to compound wealth at rates above 20% annually for decades more. This wasn’t luck. This was skill meeting discipline meeting patience, repeated daily for 60+ years.

And remarkably, he did it while remaining fundamentally unchanged. He lived in the same Omaha house his entire adult life (bought for $31,500 in 1958). He maintained the same friendships for decades. He ate hamburgers and Cherry Cokes while building a trillion-dollar empire. His growing wealth was just a way of keeping score, not a ticket to a new lifestyle.

This consistency extended to his values. He championed philanthropy, co-founding the Giving Pledge with Bill and Melinda Gates, convincing over 250 billionaires to commit hundreds of billions to charitable causes. His $31 billion donation to the Gates Foundation in 2006 remains one of history’s largest philanthropic gifts.

What happens next?

As Gregory Abel takes over, questions abound. Can Berkshire thrive without its legendary leader?

Abel isn’t a stock-picker. He came up through the energy business. The December departure of Todd Combs, one of Buffett’s investment lieutenants, to JPMorgan adds concern. Berkshire’s record as an operator has been patchier than its investing performance. BNSF’s margins have disappointed, and the Kraft-Heinz merger proved disastrous (the company announced a split in September).

With $380 billion in cash and interest rates declining, pressure will mount on Abel to deploy capital. He may lean toward utilities or Japanese trading houses, his areas of expertise, rather than pure stock-picking. Change will come, slowly but certainly. Rising institutional ownership will likely push Berkshire toward more typical corporate governance.

The bottom line

Warren Buffett’s achievement wasn’t just building wealth. It was doing so through a business structure that was absolutely unique and brilliantly designed.

The insurance float provided patient, low-cost capital. The focus on quality businesses with moats ensured consistent returns. The careful use of leverage amplified those returns. The impeccable reputation kept shareholders patient and gave access to unique deals. And the discipline to say “no” when valuations got excessive preserved capital for better opportunities.

His lesson is deceptively simple: Find great businesses, use capital wisely, stay patient, and remain in the game. Execute this strategy for decades, let compound interest work its magic, and watch single-digit annual outperformance transform into generational wealth.

But as millions have discovered, it’s simple but definitely not easy. The hard part isn’t understanding the math. It’s having the discipline to stick with quality investments through crashes, the courage to buy when others panic, the patience to hold for decades, and the wisdom to know when valuations have gotten ahead of reality.

The Oracle has spoken for the last time as CEO. He leaves behind not just a trillion-dollar company, but a masterclass in long-term thinking. His message echoes across seven decades: Slow and steady doesn’t just win the race. It laps the competition so many times they stop counting.

And right now, with $400 billion in cash, he’s sending one final message: Be careful out there. The game might be getting dangerous again.

Sonia Boolchandani is a seasoned financial writer She has written for prominent firms like Vested Finance, and Finology, where she has crafted content that simplifies complex financial concepts for diverse audiences.

Disclosure: The writer and her his dependents do not hold the stocks discussed in this article.

The website managers, its employee(s), and contributors/writers/authors of articles have or may have an outstanding buy or sell position or holding in the securities, options on securities or other related investments of issuers and/or companies discussed therein. The content of the articles and the interpretation of data are solely the personal views of the contributors/ writers/authors. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their specific objectives, resources and only after consulting such independent advisors as may be necessary.