For Suniti Dhindsa, participating at The Earth Collective’s weekend market at Sunder Nursery in the national capital is a weekly ritual. The founder of Sue’s Homemade Preserves, a homegrown brand that sells gourmet jams, jellies, pickles, fruits, syrups and drinks sourced from her orchard ‘Serendipity’ in Pauri Garhwal, Uttarakhand, uses the organic bazaar to reach out to consumers who opt for healthy and eco-friendly lifestyle choices, and look at the origin of a product that can bring value to the table.

“Our products are handcrafted using natural and organic ingredients created from seasonal fruits and vegetables. Today, the consumer is mindful of his/her choices and looks for such niche offerings—the reason why we book a table (at the market) every year,” says Dhindsa, who has been exhibiting at The Earth Collective market for over five years now. The market is known for its quality-controlled curation of fresh farm produce like coffee, milk products, artisanal grocery, sustainable home care products, live cooking stations, vegan meals and more.

The Earth Collective’s weekend market is one of the many bazaars and melas that are buzzing with activity, especially around the festive season, where visitors can not just shop, eat, indulge or walk in the open, green spaces but also provide a business opportunity to artisans, cottage industries and promoters of art and craft.

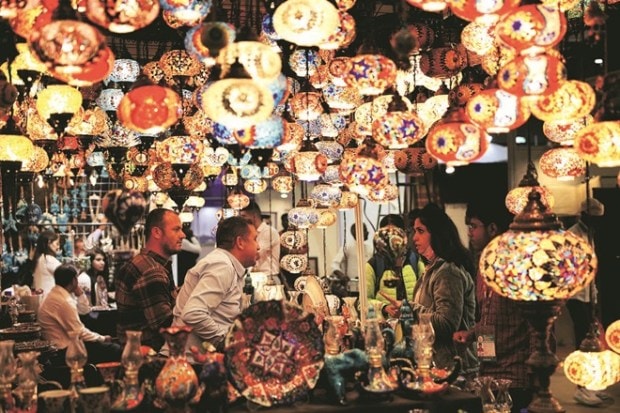

Whether it is fine chikankari prints, karigari demonstration and letterpress artworks, handmade textiles, soaps, decor, exquisite jewellery, woodwork, carpets, contemporary paintings and regional delicacies, vintage or gourmet recipes, fairs such as Dastkar Bazaar, Blind School Diwali Mela or the Indian International Trade Fair have over the years brought artists, karigars and entrepreneurs with inherent skills and strengths to capitalise on a number of business opportunities, reach out to viable consumers, earn an income and give an economic boost to the art and craft sector.

Melas and moolah

Let us first look at the economics of a mela or bazaar. Dastkari Haat Samiti (DHS), a national association of crafts people with members from all states of India, for instance, organises a crafts bazaar, an activity spread across several Indian cities, every year. It did sales worth Rs 1.5 crore at its crafts bazaar in Pune Haat at the end of 2021 just after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Last year, however, sales were close to Rs 3.5 crore during the seven days of the bazaar and are expected to be almost the same in November this year.

The duration of a mela generally ranges from seven-eight days and can extend up to 15 days, depending on the area and the city. In Hyderabad this year, a non-crafty and pure IT sector location, DHS did sales worth Rs 1.5 crore in eight days. At Dilli Haat in Delhi, its sales had even gone up to Rs 7 crore in 15 days a few years ago.

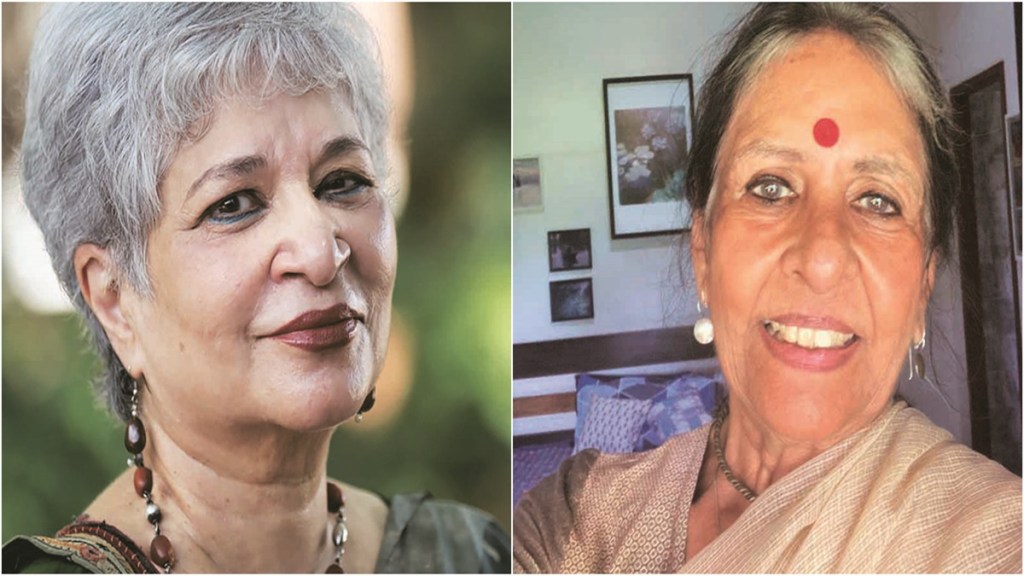

“We take an annual membership of Rs 2,000 from each craftsperson, and take an average of about 10% of their sales. They pay for their stalls and the actuals,” says Jaya Jaitly, founder-president of DHS, who has been working as a promoter and expert in Indian art and craft cottage industries for over 45 years.

In fact, Dilli Haat in Delhi permanently hosts bazaars and boasts a daily footfall of 2,000-6,000 people. This year, it will host its Diwali Mela from October 28 to November 12 in a renovated space with brickwork flooring, new energy-efficient LED lights, repainted roof and walls, bamboo ply sheets and 35 new cameras for surveillance. Officials from the Delhi Tourism and Transportation Development Corporation (DTTDC) say the revamp will not only bring more visitors to Dilli Haat but will also sustain and preserve India’s heritage with better offerings every year.

Similarly, Dastkar, a non-governmental organisation working with crafts people across India, saw sales worth Rs 2.85 crore at its 2019 Festival of Lights Pre-Diwali Bazaar that was participated by 143 craft groups. Post-Covid in 2022, even though other markets were just picking up, the Festival of Lights bazaar witnessed sales worth Rs 3.41 crore.

Meanwhile, genuine products and crafts are a differentiating factor for good sales. Textiles are most in demand with pure natural dye or ajrak cotton, bedspreads, sarees or something as creative as ajrak print on velvet in any form fly off the shelf. If the organisation’s name is known and credible for buyers, the sales and demand increase.

“A well-packaged bazaar offers a good potential to all stakeholders. (It should offer) the right ambience, a venue surrounded by trees and the beauty of open spaces, and not a hall with tables where people pay Rs 1 lakh for one-two weeks or a month with minimal return. The idea of organising a craft bazaar is not about marketing a product but applying the right skills and taking it to either public spaces like airports and railway stations, or in any form of architecture, where artisans can get the best platform to showcase their art,” says Jaitly.

Beyond display & design

The early 2000s saw a dip in craft and handloom textile sales as more malls sprang up in the cities, all sorts of imported and branded goods became available and captured popular imagination. “Organisations like ours and the participant crafts people realised the need to develop new products that were handcrafted in traditional craft techniques but were functional as well as decorative, plus well designed, stylish and appropriate to contemporary consumer lifestyles,” says Laila Tyabji, chairperson and founder member of Dastkar. Tyabji has been the face of the organisation, working with crafts people, documenting their art and preparing them for an urban clientele. Dastkar is synonymous with the Dasktar Mela, a crafts exhibition organised in Delhi every year since 1982.

In fact, city melas attract a good footfall for the sheer variety and innovation they bring from many home-grown entrepreneurs. The Blind School Diwali Mela, one of Delhi’s most sought after events, for instance, has an exciting new addition this year on display such as cow dung diyas and terracotta products, and stylish tote and jute bags. The fair will take place in south Delhi from November 3 to 9.

David Absalom, deputy executive secretary (operations), Blind School, The Blind Relief Association, Delhi, the organiser of the fair, says, “We are fully prepared to showcase a diverse range of products crafted by our visually impaired trainees and staff at the Diwali bazaar. The products encompass a wide range of items including candles, diyas, paper bags, and various cloth products. This year’s product selection reflects an overall 10% increase compared to the previous year. In addition to our own stall, there is the presence of 240 other stalls featuring an impressive collection of items.”

Over the years

The concept of a mela dates back to the 17th-century reign of Emperor Shah Jahan, when the Chhatta Chowk (covered bazaar) or Meena Bazaar located in the Red Fort of Delhi, had an exclusive display of goods in silk, brocades, velvet, gold, silverware, jewellery, gems and precious stones. It was a shopping hub for the women of the Mughal era, and was inspired by another covered bazaar in Peshawar (in present-day Pakistan), built by leading noble Ali Mardan Khan, which Shah Jahan had seen in 1646.

Over the years, ‘Numaish Masnuat-e-Mulki’, meaning an exhibition of local products, started in 1938 during the reign of Mir Osman Ali Khan, the last Nizam of Hyderabad, has gone on to become India’s oldest open-air day-and-night winter exhibition held in Hyderabad. In 2020, Numaish successfully completed 80 years with over 20 lakh visitors in attendance and with an average of 45,000 visitors every day for 46 days. Such markets were meant to have an iconic representation of crafts and boost businesses and other economic activities.

In recent years, Dastkar, a non-government organisation working with crafts people across India, held its first ‘craft bazaar’ in 1981. “Over the years, one has seen a huge growth in the number of bazaars/melas, and also a huge growth in their popularity. For the crafts people, participating in a craft bazaar results in both retail sales as well as bulk orders from Indian lifestyle stores and boutiques and export buyers. Craft bazaars also teach vendors about the importance of getting the right colours, sizes and finish. They are a huge learning in urban consumer tastes and demands,” says Tyabji of Dastkar.

For the melas and markets to achieve the desired objectives, location and right partners are key. The weekend market by The Earth Collective, encouraged by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), for instance, is held on Sundays in summers and on Saturdays and Sundays in winters. It brings carefully curated sellers with the expertise of healer and plant-based cook Meenu Nageshwaran, who is also the founder of The Earth Collective. Nageshwaran has been running organic markets since 2015 and switched to Sunder Nursery in 2019 for its location, right footfall and engagement with ‘serious health food shoppers’ who like to have fun in the sun.

“Nowhere in India can we get a better partner than Sunder Nursery, a space that is safe for all age groups, families and the well-heeled. The market is foreign ingredient-free market, seasonal and locally produced in every way. It has also phenomenally grown in the number of tables going up—from 21 on Saturdays to over 50 vendors on Sundays,” says Nageshwaran, who is planning to expand to other cities if she gets the right partners genuinely interested in such services.

Clearly, the market as a service creates value, both economically and socially, providing the health/ environment-conscious visitor to opt from many choices. “The market is an opportunity for over 50 individual and boutique vendors, including small-scale farmers, a much needed economic opportunity and encouragement. At Sunder Nursery, we seek partnerships with groups to fulfill development objectives,” says conservation architect Ratish Nanda, chief executive officer of AKTC, who has been instrumental in restoring Humayun Tomb and Sunder Nursery in Delhi.

Challenges galore

It’s a different story that such melas and bazaars also have a few drawbacks. For instance, they are quite seasonal in nature and cannot be held in the height of summer or monsoon months. This leaves quite a narrow window with just the festive season around Dussehra, Diwali, Gur Purab, Christmas and New Year, to increase footfalls and purchases.

Such bazaars are more of a money-making business for most entrepreneurs, feels Jaitly of DHS. “The success of haats has left traders and crafts people greedy for money. Organisers charge exorbitant rents from Rs 50,000 to Rs 75,000 to over Rs 1 lakh for a stall for eight days. There are only a handful of craftsmen, over 500, who are being circulated within the original craft groups like Dastkari Haat Samiti, Dastkar and The Crafts Council (set up by Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay). But the fly-by-night entrepreneurs are also digging into this limited pool of craftsmen. A big corporate or an entrepreneur couple can earn money on the side by doing a deformed version of a bazaar without even knowing what the craft is all about,” says Jaitly.

For Tyabji of Dastkar, there has been a realisation, both in India and the west, that the attributes of craft and handloom— environmentally friendly, with low carbon footprint, made by hand and non-pollutant processes from natural products—are better for our world.

“Sadly, customers tend to be much more price conscious when buying from crafts people than when they are shopping branded goods in malls, even when prices at a bazaar are cheaper, and a similar handcrafted product is usually less expensive than its industrially made counterpart. Compare an embroidered leather jooti to Nike sneakers. Visitors to a bazaar bargain in a way that would be inconceivable in a mall or designer store. As a result, crafts people increase prices so they can then lower them to please the bargain-hunting customer—a vicious circle,” adds Tyabji.

On the other hand, artists like sculptor Anju Kumar feel melas have lost charm for many reasons, one being the limited time period and space to display. Today, Kumar’s label Studio Anmol is a flourishing ‘by-appointment only’ pottery venture in Gurugram. She has been ambitiously showcasing and selling handcrafted pottery, paintings, urlis, floor lamps and innovative mandalas at a mela in the city every year, but it changed a decade ago when she started her annual exhibition just before the festive season at her studio. The switch led to a completely different business approach which offered customised display of her works and high footfall in her studio. Kumar has seen visible changes in people’s buying attitude, the biggest reason why she stopped displaying at bazaars.

“In the 90s, there were a select few bazaars and we used to get authentic buyers who valued art and aesthetics. Today, melas offer a good platform to meet, greet, display, eat out and have fun but many don’t come to shop. The business at melas is blurring and there is a need to have a valuable business proposition for creators,” adds the 59-year old potter.

Trade initiatives

On a bigger scale, trade shows and craft fairs are reducing dependence on imports and boosting domestic manufacturing by focusing on ‘vocal for local’ and ‘local for global’. The Indian Handicraft & Gift Fair (IHGF), for instance, witnesses over 100 countries as buyers for the housewares, home furnishing, furniture, festive décor, fashion jewellery and essential items it offers. The 56th edition of the fair was organised by the Export Promotion Council for Handicrafts (EPCH) in Delhi.

EPCH estimates say the country saw Rs 30,019.24 crore ($3,728.47 million) in overall handicraft exports during the year 2022-23. A year earlier, India exported handicraft goods worth Rs 33,253 crore in 2021-22. “Since 2014, the show has opened its gates to volume retail buying from renowned domestic players and continues to host visitors from major Indian retail/online brands including Amazon. com, DLF Brands, Fabindia, Home Centre India, Home 360, ITC, Indian Bazaar, Miniso Lifestyle, Snapdeal, Spencer Retail, Reliance Trends, and more,” says R K Verma, executive director, EPCH.

Similarly, the annual India International Trade Fair(IITF) organised by the India Trade Promotion Organisation (ITPO) in New Delhi witnesses around 3,000 domestic and foreign exhibitors from several countries. This year, the fair is scheduled from November 14 to 27 in the newly built halls of the International Exhibition cum Convention Centre (IECC) named Bharat Mandapam at Pragati Maidan in the national capital.

The international Surajkund Mela held every year in February brings a versatile range of craftsmen and artistes. Shilp Samagam Mela, too, is aimed at empowering marginalised communities and hosts craftsmen in Lucknow, Amritsar, Bhubaneswar, Chennai, Nagpur and Patna.