Shinzo Abe, a political blue blood groomed to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather, former Japanese prime minister Nobusuke Kishi, will be remembered for a long time for remaking that country following an asset price bubble collapse in the early 1990s that threw the country into a period of economic stagnation known as “the Lost Decades”.

Abe, who was tragically assassinated just over a year ago, will always have a special place in the hearts of Indians for the significance he attached to Japan-India ties. During the Cold War period, Japan and India maintained a politely distant relationship. But Abe changed all that by becoming the first Japanese prime minister to visit India three times, and his speech in Parliament during his very first visit in 2007 will remain a reference point for the relationship between the two countries. Quoting from the book of Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, Abe told an audience that had not yet absorbed the full import of the historic shift he was seeking in Japan’s relations with India that there was “a Confluence of the Two Seas” and the “Pacific and Indian Oceans were a dynamic coupling as seas of freedom and prosperity”.

This vision of the Indo-Pacific as a single strategic space—in which both countries had a stake—would shape Japan’s relationship with India for years to come and draw India into a larger cooperative partnership, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), that would bind it more closely to not just Japan but also the US and Australia.

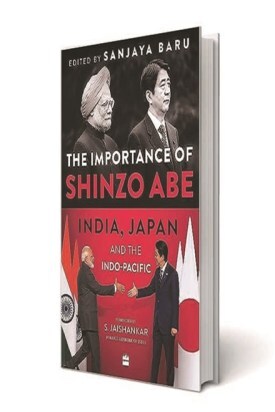

The Importance of Shinzo Abe, edited by former journalists and public policy analyst Sanjaya Baru, is a fitting homage to the memory of the former Japanese prime minister. The book brings together experts from diverse backgrounds to evaluate Abe’s contribution and the future of Asia and Japan-India relations. The 16 essays by people who knew Abe or his work well makes for insightful and absorbing reading to celebrate the statesman as much as the geopolitical strategist. They give a sense of the void Abe has left behind.

One of the crown jewels of the book is the masterful foreword by external affairs minister S Jaishankar who worked closely with Abe even when the latter was not holding any official position. Jaishankar recalls how much Abe was willing to go out on a limb for India. One of the most complex negotiations that took place during Abe’s stewardship was on India’s nuclear cooperation agreement. Even when the US-India agreement was under negotiation, Abe understood its larger significance. He, therefore, readily concurred with the thought that something similar should be undertaken with Japan as well. Abe’s leadership, Jaishankar writes, enabled the two sides to walk the difficult path with the dexterity required to finally reach the destination.

The importance of the book lies in the fact that it breaks away from the standard international relations literature in both countries. Heavily influenced by Western scholarship, there is an overwhelming tendency to view the India-Japan relationship merely through the prism of Big Power rivalry in Asia that is the China-US rivalry. While both Japan and India have shared concerns about China and share a friendship with the United States, there is a far more important historical factor defining India’s view of Japan. The essays give a fresh perspective on the issue.

The book also offers much more than just Abenomics – a term most Indians with interest in economics and international relations, are familiar with.

Baru himself sets the tone of the book in the introduction. Abe, Baru writes, was the only head of government who regarded Manmohan Singh as his mentor’ and Narendra Modi as aclose friend and partner’. “Abe played a vital role in constructing the new edifice of Japan-India relations from 2006-2022, building on the foundation led by his two immediate predecessors,” Baru writes.

The book is divided into three neatly divided sections. While the first examines the domestic politics of Abe, the second is devoted to an examination of his impact on India-Japan relations. The third examines in detail Abe’s conceptualisation of the Indo-Pacific and the Quad. This clearly is the section that Indian readers may be more interested in, as Abe was the principal architect of both these key geopolitical constructs of the early 21st century. As Purnendu Jain notes in his essay, Abe also introduced a new and important term, `Broader Asia’ which highlighted India’s centrality in Japan’s vision of Asia. Even though the Quad didn’t succeed the first time, after Australia pulled out of it in 2008, Abe made it his priority as soon as he returned to power in 2012, and the grouping was eventually revived in 2017.

Readers would also get a sense of the unusual career progress of a man, who enjoyed unparalleled power in modern Japanese politics. He became Japan’s youngest prime minister in 2006, at age 52, but his first stint abruptly ended a year later, because of his health. But as his health conditions improved, Abe made a comeback and left office two years ago as Japan’s longest-serving prime minister.

That he was a “man acutely attuned to the shifting sands of global geopolitics” is best summed up by Ravi Velloor in his essay. Abe, the author says, was neither a “reflexive China skeptic, as some in Beijing, and a few in Southeast Asia, have sought to see him”, not a “sentimentalist, as thought by some in New Delhi.” He was open to cooperating with China but at the same time sought to build new alliances to keep Beijing in check”.

No wonder, Jaishankar has said, whether you take the extreme right in India, or extreme left, Japan is one of the few foreign policy issues on which there are no differences. The Importance of Shinzo Abe does more than full justice to the memory of a remarkable friend of India.

The Importance of Shinzo Abe: India, Japan and the Indo Pacific

Edited by Sanjaya Baru

HarperCollins

Pp 258, Rs 699