By Amitabh Ranjan

In July 2023, a video went viral of a dominant caste man, reported to be a Brahmin, urinating on a tribal man in Madhya Pradesh. The latter sat slouching and the culprit, identified as a ‘pandit’, towered over him, urinating on his face and body. More disturbing than the incident was the support the culprit subsequently received from his community.

In September 2024, in Karnataka’s Dakshina Kannada district, a 67-year-old Dalit man was brutally assaulted by a high-caste Gowda shopkeeper with a wooden pole when the former sought shelter from heavy rain and wanted to rest near the shop. More recently, in Uttar Pradesh’s Etawah, a group of upper-caste men allegedly tonsured the head of a katha vaachak (religious preacher) and his aide after finding that they hailed from the Yadav community. Shortly after this incident, in Odisha’s Ganjam district, men of the Dalit Pana community were beaten up and forced to crawl with grass blades between their teeth and also to drink drain water by so-called Savarnas (dominant castes). They were alleged to have smuggled cattle which came out to be a falsehood.

These are just a tiny sample from a regular flow of such news from across India’s vast geography and cultural landscape. The political dispensation of a state hardly makes a difference. Caste consciousness, in all its shameful manifestations, is ingrained in the Indian psyche, and except the occasional expression of disgust and surprise, such incidents hardly shake the national conscience in any effective way. But is it just an Indian phenomenon?

Caste beyond borders

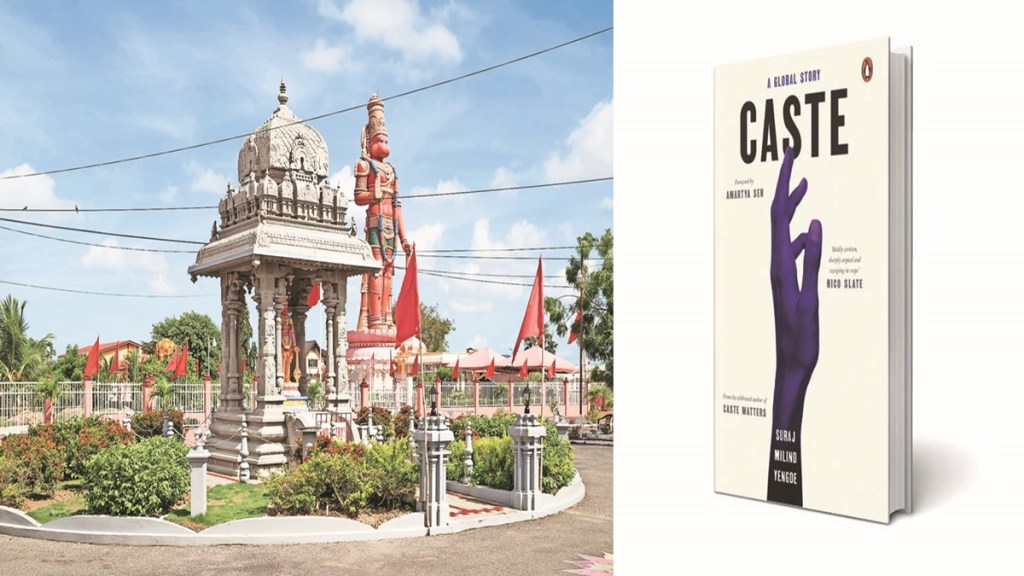

After penning Caste Matters and co-authoring The Radical in Ambedkar, Suraj Milind Yengde has come out with his latest to shed light on caste’s obstinate tendency to exist and stir societies in faraway lands and climes. Caste: A Global Story is an outcome of the author’s decade-long research based on historiography, archival resources, ethnography and personal encounters, bringing to the fore contemporary Dalit experiences among the Indian diaspora from the Caribbean to Europe, to Africa, to the Middle-East and to South Asia.

A WEB Du Bois Fellow at Harvard University, Yengde is a world-renowned scholar on caste studies. Named among the ‘25 Most Influential Young Indian’ by GQ magazine, he spent his childhood in Nanded, the headquarters town of the district by the same name in Marathwada. The region has been home to one of the most radical forms of Dalit politics for over a century where visions of Kabir and Ravidas found resonance among the underprivileged before—aided by a Dalit-Black bond and BR Ambedkar’s ideas of fighting upper-caste dominance —it created an early template of Dalit political activism. The author writes with a position of seeing and experiencing caste politics at close quarters.

Literature as resistance

A deep insight is offered into literature becoming a powerful starting point of Dalit assertion of identity and dignity. It has been a way to reclaim an area, which from time immemorial remained out of reach for the oppressed and as an exclusive domain of the dominant, particularly Brahmins. It helped challenge the age-old narrative of impurity and punishment and assert Dalit agency. A comparative study of Black and Dalit literature brings out similarities and points of divergence. While both said how discriminations were institutionalised, Dalit literature looked at caste hierarchies couched in religious and social sanctions whereas Black subjugation stemmed from centuries of slavery and a system of apartheid based on colour. What tied the two strands was a spirit to rise above hardened debilitating subjugation.

A substantial fieldwork is done in Trinidad, one of the earliest destinations of indentured labour from India where 40% of the population is of Indian origin. A majority of them belong to low-caste hierarchies. Yengde meets community leaders and tries to understand the caste dynamics on a distant land from their ancestors’. Do castes play a role in Trinidadian society? Interestingly, they do, but only in religious institutions and in trying to find worship and fellowship in the Hindu dharma. They are nearly absent in people’s lives in terms of intense rigidities found in India. Conversations with people like Pandit Amar Sreeprasad, an Ahir by caste; Pandit Parasaram who draws a Brahmin lineage; and Ravi Maharaj, an RSS functionary, are interesting and revealing.

The author traces anti-caste movements across the world, their political assertions, setbacks, achievements. What offers an interesting insight is how Dalit organisations beyond the shores are not sponsored or supported by India-based institutions. They do appear as a disparate set of anti-caste believers under the banner of Ambedkar, Ravidas, Valmiki, Dalit Christian or Buddhist congregations, but somewhere their commitment to raise their community issues and seek social justice unite them into a single bloc.

Yengde makes the point that the ability of caste to transcend time and space must be analysed through its multiple ‘diasporic nations’ that draws from one site of origin —India. He has also been immensely successful in bringing out parallels that exist in experiences of caste and race oppression, making a case for a global solidarity to fight inequalities. At the same time, an appeal goes out to dominant castes, who are carriers of social and religious creed that cannot tolerate human equality, to self-educate and agitate against the caste system rather than stand by it.

Thought-provoking, the book offers quite a few new insights into caste dynamics in the global village that we live in. To borrow from Amartya Sen’s crisp Foreword, nearly verbatim, it is a remarkable work to understand and confront the challenges of cast-in-stone inequalities worldwide.

Caste: A Global Story

Suraj Milind Yengde

Penguin Random House

Pp 384, Rs 899

The writer is a former journalist who teaches at Patna Women’s College.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of FinancialExpress.com. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.