By Mohit Hira

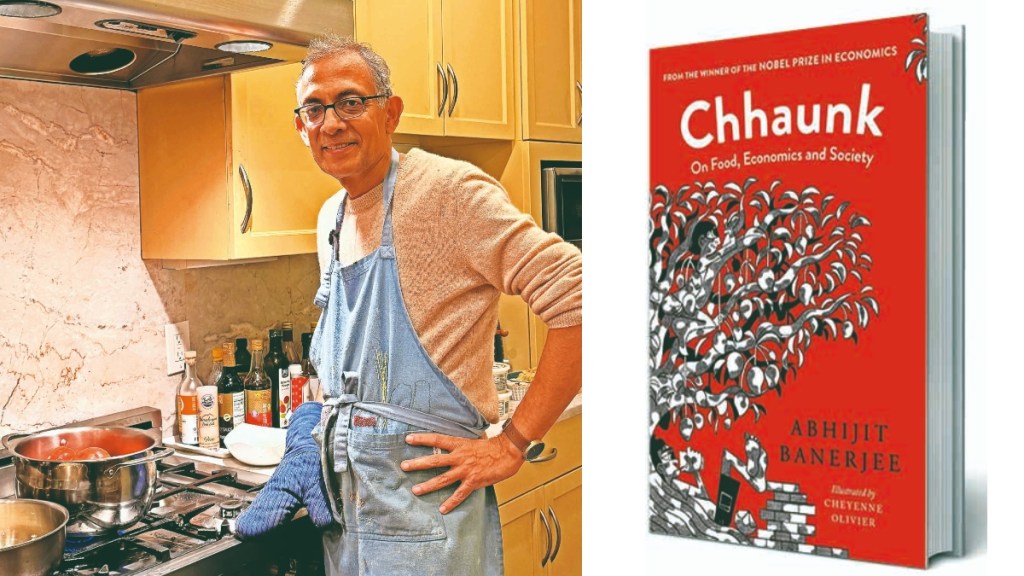

Abhijit Banerjee’s Chhaunk: On Food, Economics and Society isn’t just a book. It’s a mélange that effortlessly blends memoirs, a personal diary, economics, social sciences, history and, of course, recipes. Nostalgia is as integral to the book as salt would be to khichdi (and there are some worth-trying khichdi recipes in it).

Unlike the predictable fare laid out at hotel buffets, this is a meticulous curation of many flavours laid out for a reader to sample in no particular order; though, it would be good if you started at the beginning (the section called Economics and Psychology)—the appetiser as it were—and proceeded down to the main course (Economics and Culture) and the dessert (Economics and Social Policy). I’m quite sure the Nobel Laureate-turned-author did not have this three-course meal in mind when he wrote his fourth book, but that’s how I’m devouring it.

And the real chhaunk— or tempering—isn’t anything he’s written about, but the exquisite woodcut-like illustrations by Cheyenne Olivier that, for some inexplicable reason, remind me of Sergio Araginés’ marginals in MAD magazine. Go figure!

But before I go further, a disclaimer: Abhijit Banerjee and I are connected, albeit in a way that he will not recall. He had a Yashica SLR camera that he was selling in 1988 (or thereabouts) in Calcutta, and I bought it off him for the princely sum of Rs 3,500 (worth around Rs 15,000 with inflation factored in today). I still have the camera and, though it hasn’t been used in a while, it will probably work. Being the squirrel that I am, I will not get rid of it, perhaps because of its provenance. But the reason why I possess it is because Abhijit’s brother Aniruddha (Ani, as we fondly called him)—who’s mentioned briefly in Chhaunk—was a colleague.

And their mother, a Maharashtrian married to a legendary economics professor, occasionally fed us at their home in Ballygunge. The book is, quite naturally, a trip down memory lane for an incurable romanticist who ended up marrying another advertising colleague and discovered the subtle tastes of Bengali cuisine along the way. The Banerjee siblings are the product of a mixed marriage, as are my children. And both our offspring are also foodies—one loves spice, and the other sweets.

Chhaunk fondly recounts dinnertime conversations and Brit wit, a flavour that we’re familiar with thanks to Sindhi sai-bhaji accompanied by tomato chutney with khejur (which, incidentally, is one of the few typos that Juggernaut’s editors sadly missed). The well-informed Indian reader will discover that the book is, therefore, a delectable exploration of the intricate relationship between culinary traditions that are familiar but also new, economic systems and cultural practices.

Much like the gastronomic technique it is named after—a spice-infused oil that transforms a dish—the book sprinkles nuanced insights that elevate our understanding of social sciences. The Nobel Laureate approaches economics not as a dry, number-driven discipline that bored me at university, but as a vibrant, living narrative deeply intertwined with human experience.

By using food as his primary metaphor, Banerjee makes complex economic concepts accessible and engaging. Its most compelling aspect is its exploration of how economics and culture continuously shape and influence each other. He delves into fascinating examples that challenge conventional thinking. For instance, he observes how the British systematically undermined Bengali entrepreneurship in the early 19th century, which probably contributed to a cultural stereotype that prevails even today—that of Bengalis being more interested in intellectual pursuits and culinary experiences than business.

Key themes in the book include the role of trust in economic transactions, how social networks facilitate economic exchanges, cultural variations in economic behaviour, and the complex interplay between economic opportunities and social practices.

Abhijit Banerjee’s analysis of the hundi financial transfer system in a chapter alliteratively titled ‘Trust and Trade’, serves up a nuanced understanding of traditional economic networks. He argues that economic interactions are fundamentally human, emphasising that we are ‘first human and then economic agents’. Written with the characteristic wit that runs through the Banerjee family, and intellectual depth, Chhaunk is a light yet satiating digest.

The essays are easy in style but profound in content, making complex economic concepts consumable. His personal anecdotes and observations add warmth and relatability to academic discourse and offer unique insights into regional economic and cultural dynamics: the differences between Bengali and Gujarati business cultures, for example, provides a rich, contextualised understanding of economic behaviour.

Just as a measured sprinkling of spiced oil can elevate an ordinary meal, Abhijit Banerjee suggests that small, nuanced interventions can significantly impact economic and social systems. There is, for instance, a vividly evocative description of a “sanyasi, naked from the waist up” and his seductive sucking of a mango that Cheyenne brings to life in a simple but expressive illustration.

And in a manner reminiscent of EM Forster’s pithy “only connect” in Howard’s End, he effortlessly transits to the banquets of the Middle Ages, and later to the nawabs of Lucknow (another familiar city) and their role in economic development. He also invites readers to challenge stereotypes and think more deeply about the invisible threads connecting our economic and cultural experiences.

For economists, sociologists, and curious readers alike, Chhaunk offers a refreshing and intellectually stimulating perspective on how we live, eat and interact in an increasingly complex world. And for foodies, there are recipes aplenty from many lands to experiment with.

The kind of book one would love to nibble or devour, depending on one’s appetite.

Mohit Hira is co-founder, Myriad Communications, and venture partner at YourNest Capital Advisors.

Chhaunk: On Food, Economics and Society

Abhijit Banerjee

Juggernaut

Pp 352, Rs 899