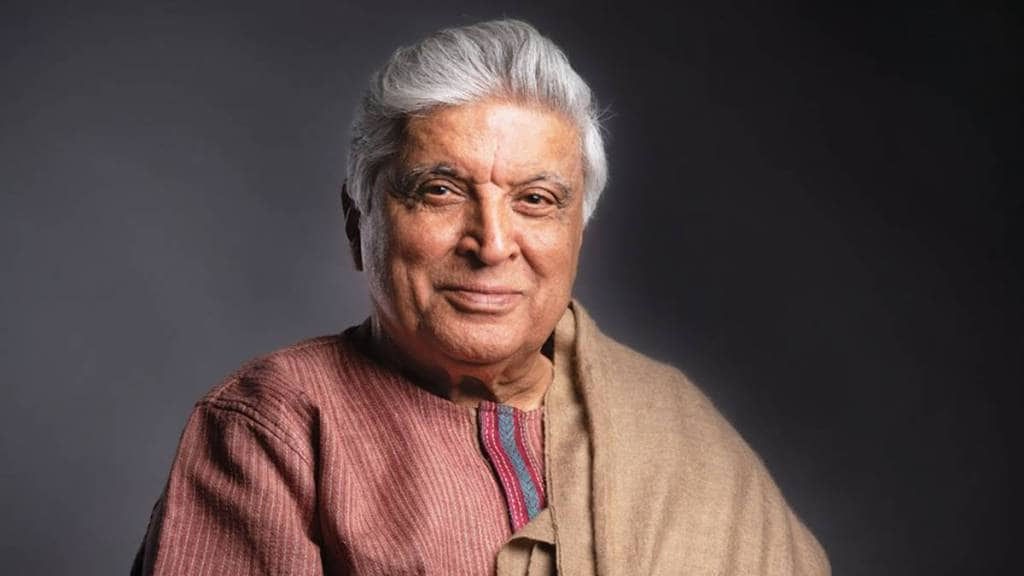

A poet, lyricist and song-writer, Javed Akhtar has given us several unforgettable songs, poems and films. Interestingly, his life is no short of a Bollywood film either. Born to a diehard Communist father, Akhtar, fondly called Jadu (magic), thought Joseph Stalin was his grandfather. Having lost his mother at an early age and abandoned by his father, he was left with relatives; some adoring, others not so much. Once in Bombay, what followed was again a life of immense struggle, nowhere making him bitter or dejected. Then came the breakthrough as he teamed up with scriptwriter Salim Khan, and together they delivered one blockbuster after another— Sholay, Deewar, to name a few. Then came the 1981 film Silsila, for which its maker Yash Chopra asked him to write the songs. Everything else is history.

The thing about Akhtar is that he is as much about literature as is about politics. “(In my family), I had politics on one side and literature on the other. It was natural that I’d be influenced by both,” he says in his conversational autobiography Talking Life: Javed Akthar in Conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir. So, when Akhtar was hosted by real estate company TARC (The Anant Raj Corporation) for a book signing event in Delhi, the conversation had to steer through language, writing, Bollywood, and contemporary issues. Edited excerpts:

In the book, there appears to be a lot of admiration for Urdu poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz. The question is regarding the language Urdu. Because of the partition of the Indian subcontinent, the language suffered—the poets and writers were divided and so was the language. What are your thoughts on this?

It was a tragedy, and because of partition, not only Urdu but the subcontinent suffered. It was so unreasonable and illogical, which is being proved everyday now and is becoming more and more obvious.

For Urdu, there was a time I used to feel very concerned about its future. But now, my concern has grown as all indigenous languages of our country are in a very precarious state. Today, parents want to send their children to English medium schools. I am not against English. On the contrary, I believe every child should know English and be fluent and comfortable with it.

Having said that, the prize we are paying of learning English isn’t right. A child should know her mother tongue. A language isn’t just a vehicle of communication. It is a vehicle that carries tradition, continuity of culture. And when you cut a child from her language, she loses the sense of history and culture, a sense of belongingness, and becomes rootless. It was what is happening, which is not advisable.

Interestingly, Urdu is a different phenomenon here. In a way, it was never as popular as it is today. You go to any bookstore selling Hindi books and ask which are the top 10 most-sold books, all of them would be of Urdu writers but printed in Devanagari. So what is diminishing is the script and not the language. Just ask anybody in Delhi, UP or Punjab to speak in a cultured manner, chances are she would start using Urdu words. So, fascination is there. But the fact still remains that all our indigenous languages are in bad shape.

While songs used to be a prominent part of Bollywood films, that seems to have declined. How do you look at this?

It is not happening in a void. Films are not made by Martians but by people who are a part of society. So, whatever happens in society, reflects or manifests in our films.

The thing is that language is going away from our society. On top of that, the attention span is shrinking, the tempo of music has become almost frantic, which makes words lose their value, because for words to go deep into the psyche, there needs to be space for them. So when the tune is fast, words become irrelevant.

While several yesteryear songs are still remembered and listened to, that is hardly the case with the present lot. What, according to you, is the reason that most of the contemporary Bollywood songs are so forgettable?

It is not that today’s writers cannot write. Rather, they don’t get the chance to write. The tempo of the music has increased. Most songs are now played in the background. There is no lip sync, so they are not a part of the story. They don’t capture the personal feelings of sorrow, happiness, love, and heartbreak.

Now, there is just a generic situation, such as a celebration, and music is played there. The earlier songs captured emotions and were part of the storyline. A song was like a scene. But now songs play in the background, it has no relation with the present situation, so how can they be so effective?

In the book, you say, “Art can only survive if it is secular.” Can art remain secular in an increasingly non-secular secular society?

Would you call Michelangelo’s paintings at the Sistine Chapel secular? No, they are religious. However, they appeal to your aesthetic sense. I am a non-believer, but they appeal to me too. So by secular, I don’t mean irreligious. The opposite of secular is communal. And if you are communal in any sense, on religious, or regional, or national, or linguistic basis, then you are not saying you are good, you are saying so and so is bad. And that is not good art, and will never appeal to people. This world has seen so many writers and poets. But name one poet, or writer who was a rightist.

How do you look at artificial intelligence and its impact on writers?

The fact of the matter is, you cannot stop technology. It will only advance. However, we will have to make different disciplines and laws to control that because it should be of help to the human being, and not to destroy them. So those laws will be made. Coming to AI, I don’t think right now it is capable of doing creative work. Writing a letter or a resume are different. The tech is based on data, but creative writing cannot happen only from data. There is some kind of leap of faith in creative writing.