By Raju Mansukhani

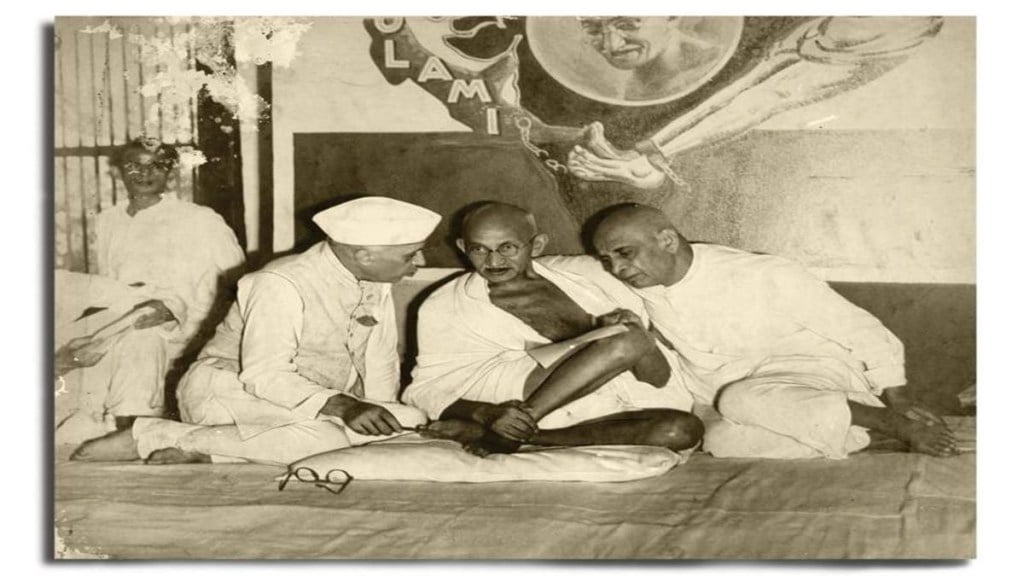

“When the current turmoil ends, the two states (of India and Pakistan) might unite by the free will of their peoples,” Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said in a press statement on September 16, 1947, almost a month after the partition of India had become a reality. Nehru believed that the division of India was a short-term political solution that could not override cultural affinities and economic compulsions. The Government of India disavowed any intention of harming Pakistan or treating it as an enemy.

Mahatma Gandhi, writing in the ‘Harijan’ on October 5, 1947, said, “It is true that there should be no war between the two Dominions. They have to live as friends or die as such. The two will have to work in close cooperation. In spite of being independent of each other, they will have many things in common. If they are enemies, they can have nothing in common. If there is genuine friendship, the people of both the States can be loyal to both. They are both members of the same Commonwealth of Nations. How can they become enemies of each other?”

Through the tumultuous months of August and September 1947, Mahatma Gandhi’s writings in ‘Harijan’ were emphatic that “if India and Pakistan are to be perpetual enemies and go to war against each other, it will ruin both the Dominions and their hard-won freedom will be soon lost. I do not wish to live to see that day.” These were not only prophetic words but filled with unfathomable pain and angst.

“If Pakistan persists in wrongdoing, there is bound to be war between India and Pakistan,” wrote the Mahatma whose life was dedicated to Ahimsa and peace but he was able to see the writing on the wall.

The horrors, public traumas and communal violence during the months of July to December 1947 were unparalleled in their scale. “It is a human earthquake,” said Nehru, in his speech in Lahore on December 8, 1947, referring to this violence and chaos which engulfed divided Punjab. The Prime Minister was witness to the migrations of millions of non-Muslims from what was to become West Pakistan and his helplessness is apparent in letters and official notes.

Nehru’s biographers, especially Sarvepalli Gopal, have chronicled the collapse of the non-League government and the communal tensions had grown as the administration could do little to prevent or stem the tide of violence and hatred. Yet no one, neither the Government of India nor the leaders of the Congress and the Muslim League, had paid much attention to this gathering potential of tragedy.

“People have lost their reason completely and are behaving worse than brutes. There is madness in its worst form,” wrote Nehru to Lady Ismay on 4 September 1947. There was a surprise and a sense of helplessness in the new government. Undoubtedly the political turmoil, migrations, killings, and massacres were unprecedented. Added to it was the attitude of the law enforcement agencies who, it was believed, had also participated in the massacres on both sides.

“It is the bounden duty of the majority in Pakistan, as of the majority in the Union, to protect the small minority whose honour and life and property are in their hands….” Mahatma Gandhi’s words from the pages of Harijan were making these heart-rending pleas.

“To drive every Muslim from India and to drive every Hindu and Sikhs from Pakistan will mean war and eternal ruin for the country,” he wrote on September 28, 1947. The Mahatma’s words, to be read almost as a clarion call so relevant to date, were falling on deaf ears.

Prime Minister Nehru took it upon himself to bring ‘his people back to sanity.” In several letters to Lord Louis Mountbatten in August 1947, he said, “I cannot and do not wish to shed my responsibility for my people. If I cannot discharge that responsibility effectively, then I begin to doubt whether I have any business to be where I am. And even if I don’t doubt it myself, other people certainly will. I am not an escapist or quitter and it is not from that point of view that I am writing. The mere fact that the situation is difficult is a challenge which must be accepted and I certainly accept it.”

His constant refrain was that “we are not going under.” The post-Partition situation, however explosive and unpredictable at all fronts, was a challenge India was ready to overcome. Through these days, the Prime Minister was travelling the length and breadth of northern India. Lahore on one day, Allahabad on the next. In his speech on 14 December 1947 in Allahabad, the city where he earned his political laurels, he said, “The battle of our political freedom is fought and won. But another battle, no less important than what we have won, still faces us. It is a battle with no outside enemy . . . It is a battle with our own selves.”

Junagadh: The plebiscite

It was Junagadh that was top of mind for the Government of India in the aftermath of Independence on 15 August 1947. What transpired in Junagadh set the stage for the politics of deception and duplicity in Kashmir in the months and years ahead.

Junagadh was a small Princely State on the west coast, and its Nawab, Sir Mahabatkhan Rasulkhanji, was an eccentric of rare vintage. His chief preoccupation in life was dogs, of which he owned hundreds.

V P Menon, the Secretary of the States Department, wrote in ‘The Story of Integration of Indian States’,“I was told, indeed, that he carried his love for dogs to such lengths that he once organized a wedding of two of his pets, over which he spent a huge sum of money and in honour of which he proclaimed a State holiday!”

Menon’s book chronicles the story of Junagadh and the political games played by the Nawab, while paying lip service to the ideal of a united Kathiawar.

On 11 April 1947, in reply to some speculations in the Gujarati press regarding the State’s attitude towards the future constitutional set-up of India, the Government of Junagadh issued a press note stating:

What Junagadh pre-eminently stands for is the solidarity of Kathiawar and would welcome the formation of a self-contained group of Kathiawar States. Such a group while providing for the autonomy and entity of individual States and their subjects would be a suitable basis for co-operation in matters of common concern generally and co-ordination where necessary.

The subterfuge had started early in 1947 when the Dewan, Abdul Kadir Mohammed Hussain, had invited Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, a Muslim League politician of Karachi, to come to Junagadh and join the State Council of Ministers. In May 1947 when Abdul Kadir went abroad for medical treatment, Sir Shah Nawaz took over as Dewan and soon the Nawab came under the influence of the Muslim League.

“Both the Jam Saheb of Nawanagar and the Maharajah of Dhrangadhra warned me that with Sir Shah Nawaz in the saddle there was a possibility of Junagadh going over to Pakistan,” said VP Menon in his book.

When the Instrument of Accession was sent to the Nawab for signature, there was silence. No reply was sent to the States Department even up to August 12, 1947, when the last date for the initiation of the signing of the Instrument of Accession was August 14, 1947.

On August 13, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, replied that the matter was under consideration.

To carry the deception further, Sir Shah Nawaz called a conference of leading citizens the same day. On behalf of the Hindu citizens, a memorandum for submission to the Nawab was presented to the Dewan.

The memorandum analyzed the dangers that would accrue to the State if it decided to accede to Pakistan.

Announcing the Accession

Having thus staged a make-believe of consulting public opinion over the issue of accession, the Government of Junagadh on 15 August announced their accession to Pakistan in the following communiqué:

“The Government of Junagadh has during the past few weeks been faced with the problem of making its choice between accession to the Dominion of India and accession to the Dominion of Pakistan. It has had to take into very careful consideration every aspect of this problem. Its main preoccupation has been to adopt a course that would, in the long run, make the largest contribution towards the permanent welfare and prosperity of the people of Junagadh and help to preserve the integrity of the State and to safeguard its independence and autonomy over the largest possible field. After anxious consideration and the careful balancing of all factors the Government of the State has decided to accede to Pakistan and hereby announces its decision to that effect. The State is confident that its decision will be welcomed by all loyal subjects of the State who have its real welfare and prosperity at heart.”

This decision by the Government of Junagadh was not communicated to the Government of India. The first intimation the States Department had of it was a report appearing in the newspapers on August 17, 1947. “I wired immediately to the Dewan for confirmation and the next day he telegraphed to me that Junagadh had acceded to Pakistan,” revealed VP Menon.

What happened to Junagadh would be important, as both the Governments of India and Pakistan recognised not only in itself but because it would serve as a precedent in the larger issues, which were still pending, of Kashmir and Hyderabad.

When Lord Mountbatten assumed the chairmanship of the Defence Committee of the Indian Cabinet, no military decision could be taken without his knowledge. His suggestion of arbitration in the case of two bits of territory whose incorporation in Junagadh State was doubtful was vetoed by Patel. But Mountbatten was more successful in persuading Nehru to rule out war and commit himself to a plebiscite in Junagadh.

HV Hodson, a senior British official who had a ringside view of these political machinations, wrote in The Great Divide: Britain-India-Pakistanthat Liaqat Ali Khan was assured Pandit Nehru would abide by the statement regarding the plebiscite in Junagadh. “Pandit Nehru would agree that this policy would apply to any other State, since India would never be a party to trying to force a State to join their Dominion against the wishes of the majority of the people.”

Hodson noted that Pandit Nehru had nodded his head sadly. Liaqat Ali Khan’s eyes had sparkled. “There is no doubt that both of them (Liaqat and Mountbatten) were thinking of Kashmir. Pakistan, therefore, had gained considerable vantage on the question of Kashmir even before the crisis broke.”

The politically chaotic, socially tragic, and dreadfully dramatic decisive months of 1947 continue to haunt us in the twenty-first century.

The author is a researcher-writer specializing in history and heritage issues, and a former deputy curator of the Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya.

(Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.)