To the extent India’s production-linked incentives (PLIs) are targeted at larger firms, rather than smaller, “inefficient” ones, these shouldn’t be equated with indiscriminate protection for domestic industry, Arvind Panagariya, chairman of the 16th Finance Commission, said on Monday.

He, however, cautioned that if the incentives were made available to “all sectors and everybody,” with focus on import-substitution industries, it would amount to “punishing competitive export industries”.

“If we use PLIs selectively to promote two or three sectors, that’s one thing. But, if (these are used as tool for) overall industrialisation, I think that’s a hard thing to do. The capital is limited… the whole industry or sectors you can’t expand by subsidising everybody. You have to ultimately rely on expansion of the industry into the global market place,” the noted trade economist told FE in an interview.

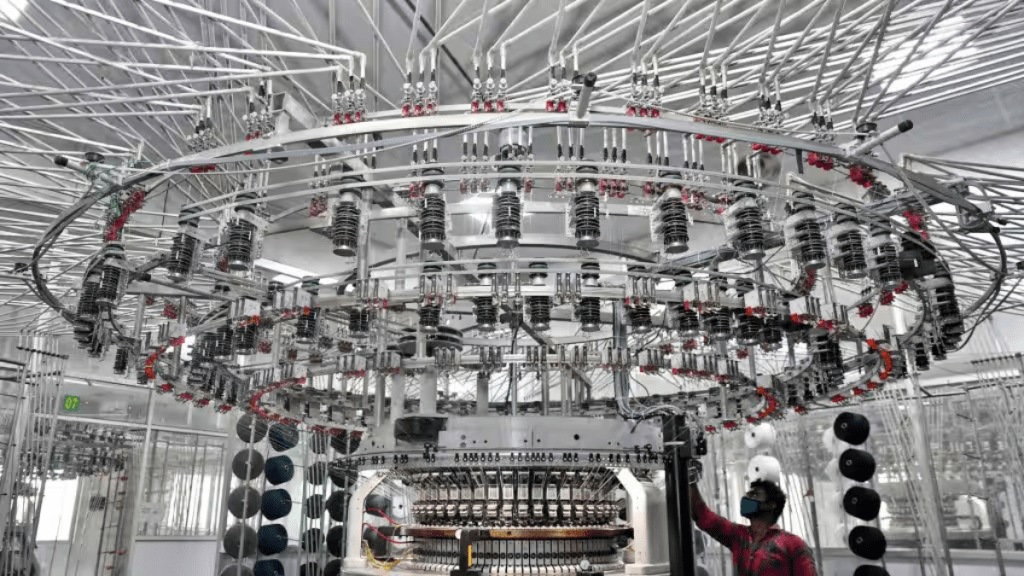

The PLI policy was launched in 2021-22. There are as many as 14 schemes now, with the government seeking to offer Rs 2 trillion in incentives by FY30. However, the schemes’ progress so far is barely par for the course. There are big lags in investments in many sectors, including high-efficiency solar PV modules, automobiles, ACC batteries and textiles, that were supposed to lead the pack.

Panagariya’s new book – India’s Trade Policy: The 1990s and Beyond — while underscoring the beneficial effects of India’s trade liberalisation since 1991, denounces the intermittent reversals, including since 2018-19, the year which saw major escalation of import tariffs, with over 42% of all tariff lines going up. The book, divided into 10 parts, chronicles the evolution of India’s trade and industrial policies, through topical newspaper essays written by the author over decades, and is due for release.

The former ADB chief economist’s comments on PLIs add to the debate over the sops funded out of the exchequer, and designed to boost India’s manufacturing prowess. Former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuraman Rajan has been critical of the policy, which he believed sought to “build gold-plated capital”. Rajan had said the government could have used the monies spent on PLIs to fund “high quality schools and universities,” capable of generating “large externalities,”including a “huge expansion in service exports”.

Panagariya, formerly vice chairman of Niti Aayog (Jan 2015- August 2017), also made a strong pitch for the country clinching more free trade agreements (FTAs), as the WTO’s Doha Round or multilateral route for easing trade further, would seem “all but dead”.

“FTAs with the Australia, UAE and EFTA are smaller ones, (the one with) the UK will be bigger. But the real big one will be with the European Union,” he said, adding that, at some point, even the US could be added to this list.

“FTAs are likely to be a big incentive for an MNC that is currently in China and is considering to move to India, as products produced in India could get duty-free access to major markets… FTA will lead to a rise in foreign investments in India,” he said.

Panagariya, however, said he no longer favoured India being part of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a free trade agreement among the Asia-Pacific nations, with China as principal constituent. “I have changed my mind on RCEP… After the Galwan incident, it’s clear that you really can’t trust China. That extends to economic areas also. So, I endorse the government’s policy, which is to try to move away from China.”