The non-conventional is conventional now. Renewable energy has made the definitive break from its sustainability moorings to reshape commercial power markets worldwide. From Kadapa to California, solar power has made headlines of late, for the lowest tariff (`3.15 per kWh) and for a record contribution (40% of power supplied for part day), respectively. Over the last fifteen years, renewable energy in India has progressed from 3% to 15% of installed capacity, and from a subsidised to competitive power source. But how sustainable is it?

The gains made are significant but not entirely assured and can regress. All renewable energy is paid on delivered output as opposed to capacity contracted, which makes it susceptible to offtake risk, thus increasing the cost of capital. Also, the risk grows as more variable renewable energy capacity is added, unless remedial measures are taken.

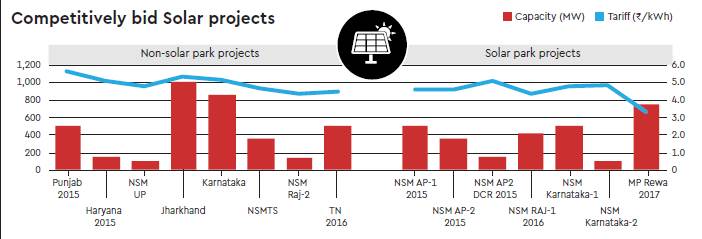

The government’s adoption of competitive bidding for large-scale renewable parks has certainly paid off. About 40% of renewable capacity addition in the last two years (6.3 GW of 15.8 GW) has come through this route. Importantly, these parks have delivered more competitive tariffs than capacity-based tenders. In recognition of this, the government has doubled its target for solar park development from 20 GW to 40 GW.

You May Also Want To Watch:

But with investors becoming more discerning, not all these will be successful. The secret lies in how well the pre-development activities and contract structuring is done. The 750MW Rewa Solar Park offers an ideal model on which to build. The park delivered a record tariff of 297 paise/kWh (or, 330 p/kWh if the 5% annual escalation is included).

Project delays are the single largest drain on a renewable project’s returns. This was avoided by Rewa by readying the entire land of 1590 hectares and securing a concessional loan to fund the infrastructure.

The creditworthiness of buyers, commonly the state utilities, is also a major concern given their poor financial health. Rewa diversified the counterparty risk by selling to a direct consumer (the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation), levying no intermediary costs. It offered three-tier payment security comprising a traditional letter of credit, a Payment Security Fund and a state guarantee.

Offtake risk is a growing menace with increasingly variable renewable energy and the limitations of our state grid. Rewa compensated for such non-availability of transmission beyond a limit. Similarly, the PPA mitigated any additional cost on account of change in law. These two safeguards removed a major uncertainty that bidders face.

The benefits delivered by renewable energy parks, in the manner of Rewa, are scalable and sustainable. They come from a sound understanding of power markets and financing, and involve projects where meticulous groundwork is done to generate real value. Project developers know they have a choice now and will selectively pick such tenders for their next best bet.

The writer, Kameswara Rao is Partner, PwC