During the first week of October 2025, when the Tata Trusts board came together to review its leadership structure, one appointment was made with no discussion. Venu Srinivasan, the Chennai-based industrialist who spent five decades building up TVS Motors as an international brand, would remain a Lifetime Trustee and Vice Chairman of the Trusts. Earlier this week, reports about Mehli Mistry being ousted from the Trusts also bore Venu Srinivasan’s name as one of the three trustees who opposed the extension of Mistry’s term with the Trusts.

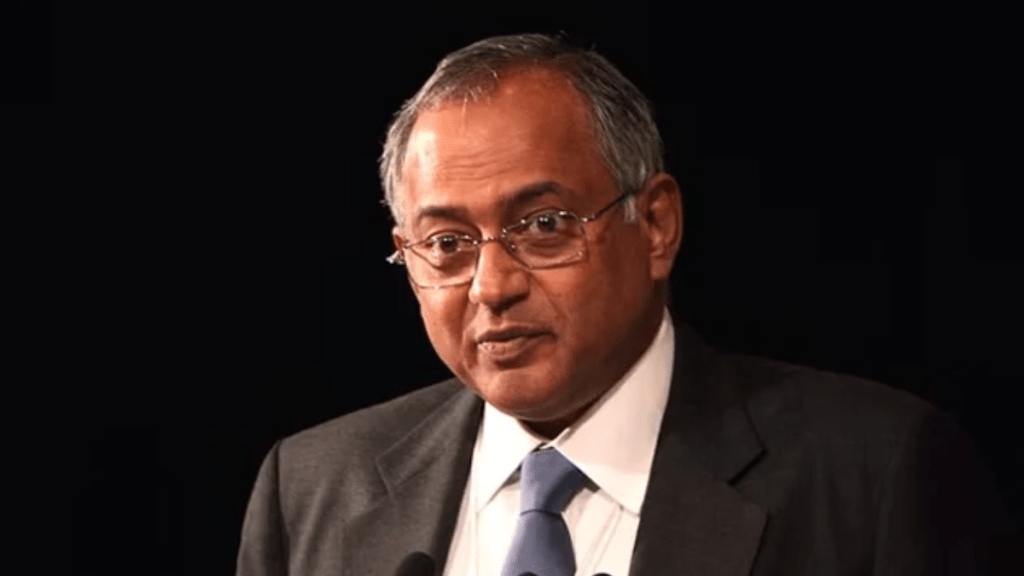

At 73, Srinivasan’s name might not be featured in India’s corporate chatter that often, although that took a turn with the entire Tata Trusts rift coming out in public. His influence across manufacturing, finance and philanthropy cannot be unseen. Today, he sits on the Reserve Bank of India’s Central Board, heads one of India’s largest CSR networks and now finds himself at the centre of the trouble brewing at Tata Trusts, the philanthropic core that holds roughly two-thirds of Tata Sons, the parent of India’s most valuable conglomerate.

The Engineer Who Started With Fixing Cars

Born in December 1952, Srinivasan is said to have begun his career fixing engines in a garage. Before stepping into leadership, he worked as a garage mechanic, studied mechanical engineering in Guindy, and earned a Master’s in Management from Purdue University, selling Bibles door to door during his student days to learn the meaning of persistence. He returned to India with an unusual conviction that Indian manufacturing could rival Japan’s in discipline and quality.

In 1979, at just 27, Venu Srinivasan took charge of Sundaram-Clayton, the holding company of the TVS Group. A decade later, his leadership was tested by one of the gravest crises in the group’s history. The Hosur plant of TVS Motor was crippled by labour unrest and financial distress throughout the late 1980s. As tensions escalated, Srinivasan took the audacious decision to shut the factory for three months in 1990. The lockout forced unions to return to the negotiating table, leading to a long-term wage settlement and a framework for cooperative industrial relations.

Emerging from that turmoil, Srinivasan realised that survival required more than peace. He turned to Japan, whose manufacturing systems were far ahead of India’s in both technology and discipline. Drawing inspiration from Japan’s Total Quality Management (TQM) philosophy, he invited Deming laureates like Prof. Yasutoshi Washio to train TVS teams on process excellence and employee involvement. By 1998, Sundaram-Clayton became the first Indian company to win the Deming Application Prize, and four years later, TVS Motor became the world’s first two-wheeler maker to earn that distinction.

Srinivasan’s messiah story feels like a page taken out of Ratan Tata’s story. In an old video on YouTube, Tata can be seen recounting a tense encounter where he personally confronted a criminal, who had 200 violent followers and had even influenced the police, despite opposition from his team. He stayed at the plant for days, ensuring worker safety and production continuity, ultimately leading to the gangster’s arrest.

“We moved from managing by instruction to managing by participation,” Srinivasan once said. The Hosur plant became a case study in how TQM could humanise efficiency.

From Suzuki to BMW — and Beyond

When the Suzuki joint venture dissolved in the late 1990s, TVS was left without a technological crutch. Srinivasan responded by building one. The 2001 launch of TVS Victor, India’s first indigenously developed four-stroke motorcycle, marked a shift from dependency to design sovereignty.

In 2013, he signed a technical partnership with BMW Motorrad to co-develop sub-500cc bikes. A decade later, TVS produces about 12% of BMW’s global volumes, including its electric model, the CE02. Then came Norton, the historic British motorcycle brand TVS acquired in 2020 for £16 million. As per media reports, Norton is being revived through a £100 million investment under his son, Sudarshan Venu.

As of 29 October 2025, Forbes pegs Srinivasan’s net worth at $5.7 billion.

The Governance Technocrat

His appointment to the Tata Trusts board back in 2016 came at a sensitive juncture, considered as the aftermath of the Tata and Cyrus Mistry feud. As per media reports, for Ratan Tata, Srinivasan’s appeal lay in his temperament: measured, discreet, allergic to spectacle. Within two years, he became Vice-Chairman of the Trusts, helping steer governance reforms and philanthropic disbursements that exceed Rs 1,000 crore annually. His recent lifetime reappointment came during a sensitive period for the Trusts, which oversee over Rs 30 trillion in philanthropic and corporate assets and control two-thirds of Tata Sons.

The Srinivasan Services Trust (SST), founded in 1996, works across 2,500 villages, focusing on water conservation, healthcare, and women’s empowerment. SST applies the same TQM discipline to social work, setting measurable goals, reducing “process waste,” and institutionalising community ownership.

For the Tata Trusts, Srinivasan represents predictability in an increasingly fluid ecosystem. The RBI’s new rules for upper-layer NBFCs and ongoing debates on the Trusts’ governance model have made stability paramount. His reappointment as lifetime trustee is, in effect, a vote for steadiness.

He remains Chairman Emeritus at both TVS Motor and Sundaram-Clayton, with his son Sudarshan and daughter Lakshmi carrying the operational mantle. His wife, Mallika Srinivasan, chairs TAFE, India’s largest tractor manufacturer, making theirs one of India’s most quietly powerful industrial families.

Over the years, Srinivasan turned TVS from a mid-sized family business into a systems-driven global company through sheer method. He built a structure that could outlast him, handing over the reins without drama or dilution. The same discipline runs through his philanthropy, where the SST works with factory-like precision to deliver an impact. Now, as it helps navigate the rifts at Tata Trusts, Srinivasan seems to remain what he has always been: steady in tone, deliberate in action and perhaps quietly holding together one of the largest institutions in the market.