By Dr Amit Tripathi

Last few years have seen sensational headlines reporting discoveries of precious metals from different parts of India. February 2020 headlines sensationalized the discovery of “300t of gold reserves” in Sonbhadra, UP; again in March 2020 headlines screamed “2,900-tonne gold mine found in Sonbhadra, 4 times that of India’s reserves”; May 2020 “223t of gold” were found in Jamui, Bihar and some other similar hyped stories.All these headlines were later found misquoted leaks or were retracted by official sources.

In professional circles, such coverage suspiciously felt like the creation of a lingering sentiment of activity leading to a flurry of discoveries through media hype, especially in a jurisdictional framework where the business of mineral exploration was effectively nationalized. Many of these “discoveries” disappeared with successive news cycles. With the recurrent media hype of red herring discoveries, it becomes necessary to evaluate the recent news of the mammoth 5.9 million tonnes of lithium reported in J&K, from viewpoint of a professional explorer. Unlike the previous headlines, this lithium find has been reported by a professional and respected organisation viz The Geological Survey of India. The news release has technically correct semantics and presents a realistic picture. This greatly enhances the credibility of the report against the backdrop of earlier breaking news headlines.

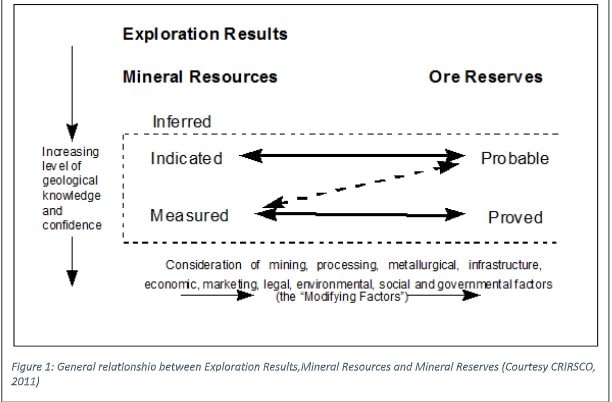

Media’s feeding frenzy, however, has twisted this credible report into another mega hype. On closer inspection the highly distorted media sensationalization becomes apparent. A major example of misquote would be the techno-legal term “inferred resource”, correctly used by the Geological Survey of India, which has been reported as“reserves of lithium” by sections of the media. These terms have specific technical and legal definitions and CANNOT be used interchangeably. In several advanced mining jurisdictions, such misquoting would be construed to be illegal for public reporting and punishable by law. According to globally accepted public reporting standards like CRIRSCO (being adopted by India) “Inferred Resource” is defined as “…that part of a Mineral Resource for which quantity and grade or quality are estimated on the basis of limited geological evidence and sampling. Geological evidence is sufficient to imply but does not verify geological and grade/ quality continuity. An Inferred Resource has a lower level of confidence than that applying to an Indicated Mineral Resource and must not be converted to a Mineral Reserve. It is reasonably expected that the majority of Inferred Mineral Resources could be upgraded to Indicated Mineral Resources with continued exploration.” Inferred resource is thus the lowest confidence level of reporting. In fact, it is not permitted to have “inferred resource” reported as a part of total resource and reserve. This “inferred resource” is required to be reported separately due to low confidence exploration in this category.

The progression of increasing geological knowledge of a prospect and confidence in its viability as a commercial enterprise is also legally defined. Several years of intense geological exploration will be essential to convert these “inferred resources” of lithium to “indicated resource”, “measured resources”, “probable reserve” and “proved reserves” and will also require commensurate investment. Establishing “proved reserves” is an essential prerequisite for any commercial utilization of lithium from this prospect. Thus, there is a lot of daylight between the cup and the lip. Beyond the hype and headlines this report of lithium in Salal-Haimana remains relevant as having identified a potential prospect for further exploration of a critical battery metal in India.

Common global occurrences of lithium and how does Salal-Haimana compares to its peers?

Bulk of global supplies of lithium come from brines – which are accumulations of saline groundwater enriched in dissolved lithium. Most lithium brines occur in closed basins in arid regions and contain 200–1,400 milligrams per liter (mg/l) (or ppm) of metal. To recover lithium, the brine is pumped to the surface and concentrated by natural evaporation in a series of artificial ponds to enhance the metal content(commonly 2-6%). This concentrated brine is then processed in chemical plants to get products like lithium carbonate and lithium metal. To be commercially viable, this evaporation process is done with natural sunlight and may take up to two years before being ready for the chemical plant.

The second geological occurrence of lithium, responsible for about a quarter of global supplies, is hosted in hard rocks such as pegmatites with a high concentrations of lithium-bearing minerals. The metal recovery process from these hard rocks requires grinding or rock followed by beneficiation and chemical processing. Higher concentration of lithium is required for hard rock occurrences to become viable as the mining and processing costs are higher than the processing of brines.

The recently reported lithium occurrence of Salal-Haimana in J&K does not fall into either of these major mineralization styles and is geologically different. This find was first reported in 1999 by the Geological Survey of India (Sharma and Uppal 1999) and mentions lithium concentrations of about 800ppm in a bauxite crust. The resource, grade distribution, and geological continuity are yet to be determined and will take major investment in thousands of meters of drilling and several years of dedicated exploration effort.

It is understood that lithium contained in the rocks of Salala-Haimana is amenable to dissolution only by hydrofluorisation with acid. This means the metal is trapped inside the crystal lattice of the host rock. Mineralogical studies conducted earlier have failed to identify the mineral phase except in most cases. This being an unusual lithium occurrence, any potential recovery of lithium from this source would require developing specific recovery technology. Such complications in recovery might require building leach vats and fine grinding of the ore, both of which are expensive processes and would be a challenge to establish commercial viability.

To summerise “beyond the hype and behind the headlines”,this discovery is an interesting prospect that needs to be further explored by a team of experts, experienced in not only finding deposits but also capable of establishing feasibility. Such a detailed exploration would require a significant investment and necessarily have to go through the intricate process of detailed exploration. As the project is in process of being auctioned for further work, it would be good if Indian business houses would set up to invest in some real research and development. It is a great R&D project worthy of a collaborative effort through public – private partnership. By no means is this a low hanging fruit to leapfrog India into the major league of battery metal producers but a challenge to the Indian exploration sector to develop an indigenous collaboration between corporate financing, professional exploration and extractive metallurgy research.

The author is Director, MPXG Exploration Pvt Ltd. The author has spent several years exploring for minerals in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) and has over two decades-long experience of working in varied policy jurisdictions globally.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.