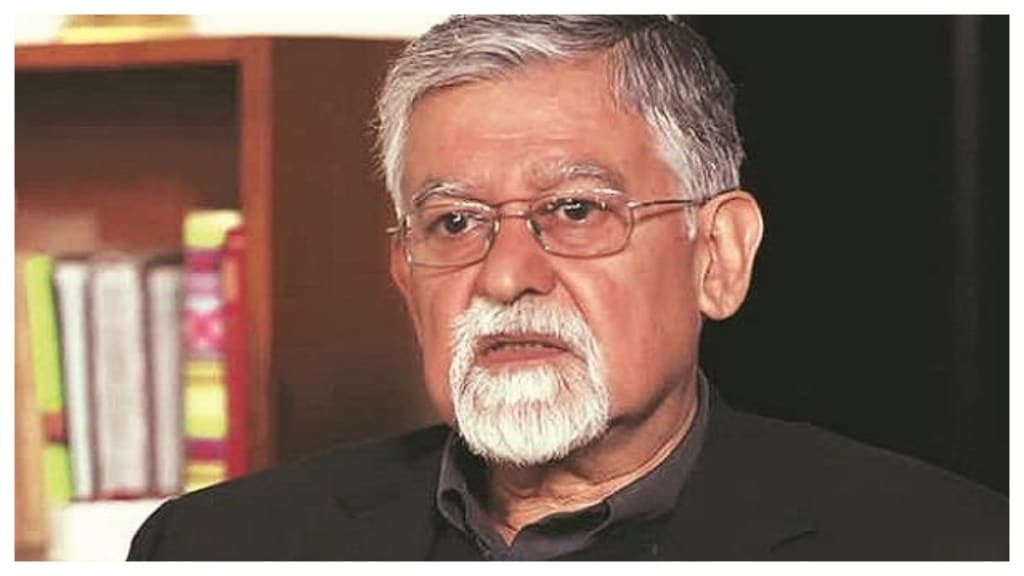

Ahead of the Union Budget for 2026-27 and an expected overhaul of the customs duty regime, economist and Niti Aayog member Arvind Virmani has underlined the need for India to address inverted duty structures, ease supply chains and facilitate labour-intensive stages of production to enhance the competitiveness of the Indian economy.

India’s weighted average customs duty currently stands at around 12%, significantly higher than the roughly 5% average among the world’s top economies. This gap, Virmani argued, places Indian manufacturers and exporters at a disadvantage in several sectors. In his view, customs reform must focus not merely on lowering tariffs, but on rationalising the structure to support domestic production, exports and integration into global value chains.

In an interview with FE, Virmani said India’s strategy to narrow this gap is increasingly centred on free trade agreements (FTAs) with high-income economies. Such agreements, he noted, can reduce effective tariff rates to well below 5%, without resorting to blunt, across-the-board tariff cuts. Beyond tariffs, he emphasised the broader objectives of improving quality, productivity and wages, supported by complementary reforms in logistics, standards and supply chain efficiency to fully realise the gains from customs reform.

Rationalising India’s Complex Tariff Tiers

His remarks come as finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman has signalled that the next major reform push, following income tax and GST simplification, will be a comprehensive overhaul of India’s customs framework. She has described this as the next big “clean-up” exercise aimed at simplifying rules, reducing complexity and making compliance easier for businesses and individuals. Sitharaman has also repeatedly flagged the need to correct inverted duty structures.

“The system is quite complex. The inverted duty structure cannot be removed 100% in all cases, but at least in the important cases where domestic production is on the margin, it could be very useful,” Virmani said, citing the information technology sector as a prominent example. These, he added, are precisely the areas the finance minister is likely to examine closely to see how far existing distortions can be reversed.

Virmani pointed to the WTO Information Technology Agreement (ITA), signed largely at the initiative of the United States, as a case study of how well-intentioned tariff liberalisation can have adverse structural effects. Under the ITA, India agreed to reduce tariffs to zero on a defined list of IT products. However, the broader manufacturing implications were not adequately assessed at the time. While finished IT products became duty-free, many inputs and components continued to attract higher duties, resulting in a pronounced inverted duty structure.

“This hurt domestic manufacturing, even in areas like simple assembly of laptops and computers, where India could have been competitive,” he said. The experience, according to Virmani, highlights the importance of carefully sequencing and designing tariff reforms to avoid undermining domestic capabilities.

While rationalising tariffs can deliver strong medium-term benefits—as demonstrated by the reforms of the 1990s—Virmani cautioned that short-term disruptions are sometimes unavoidable. “I have no doubt that this will raise the overall competitiveness and efficiency of the manufacturing system, and therefore help in enhancing the manufacturing supply chains for the domestic market. That is the key purpose of rationalising the tariff system,” he said.

Given the government’s recent policy push in electronics, including semiconductors, Virmani argued that the entire electronics supply chain must be reviewed to identify and eliminate inverted duty structures wherever possible. At the same time, care is required for multi-use inputs such as aluminium or glass, which serve multiple industries. He also stressed that any customs duty rejig must facilitate labour-intensive stages of production.

On whether customs reform should be a one-time exercise or follow a multi-year, rule-based roadmap, Virmani drew parallels with the 1990s. At that time, India was starting from customs duty levels as high as 300%, making gradual, phased reductions unavoidable. The government followed a clear sequence—natural resources, capital goods, intermediate goods and finally consumer goods—a process that took nearly a decade.

“Today, the challenge is different. Duty levels are not excessively high, but global uncertainty is much greater and likely to persist,” he said. Economic risks are now intertwined with strategic considerations, making the reform exercise far more complex and necessitating a carefully staged approach rather than a one-off move.

Analysts have argued that India should bring its average tariffs closer to the global benchmark of 5%. Virmani, however, warned against mechanically reducing headline rates. The more effective route, he said, lies in FTAs with developed, largely complementary economies. India has already signed such agreements with Australia, the UK and the EFTA bloc, and negotiations are underway with the US and the EU. These partners are all high-income economies, and the resulting FTAs could significantly lower India’s effective tariff burden.

“Such FTAs will bring down the effective or average tariff rate—potentially well below 5%. Rationalisation through targeted agreements is far more important than across-the-board tariff cuts,” he said. Revenue considerations, Virmani added, should not drive customs reform. The primary objective must be to enhance competitiveness, raise productivity and improve wages.

New Global Reality

On the broader question of whether India is moving away from tariff-led protection towards a competitiveness-driven trade policy, Virmani said the answer is no longer straightforward. A decade ago, he would have said yes without hesitation. Today, national security concerns—spanning economic, domestic and international dimensions—have become central. Components that can communicate, compute or control, the so-called “3Cs”, pose potential security risks if embedded in critical systems. As a result, tariffs cannot be abandoned indiscriminately.

This, he said, is also why India’s FTA strategy focuses on trusted partners—to build competitive supply chains while safeguarding security interests. “Simply giving up tariffs is no longer feasible,” Virmani added.