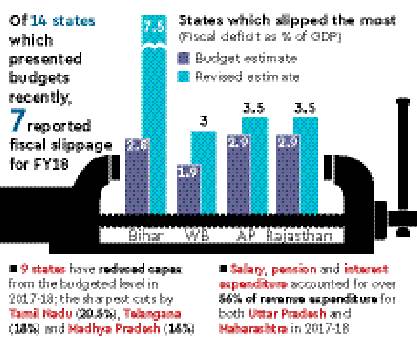

With the UDAY burden off, state governments in aggregate were expected to revert to well below 3% fiscal deficit in the current financial year, but an analysis by FE of 14 state budgets presented recently suggests they might not. As the year is drawing to a close, seven of these states have revised their FY18 fiscal deficits to be higher than projected a year ago, with the slippage ranging from a marginal 0.1 to profligate 4.63 percentage points.

Unless the other states in aggregate do remarkably better than assumed — there are slim chances of this —, the combined fiscal deficit of states in FY18 could turn out to be substantially higher than the estimated 2.69% of the gross domestic product, and possibly, cross the 3% threshold, prescribed under the respective Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Acts and the 14th Finance Commission, by a good margin.

Worse, the slippage is despite nine of the 14 states reducing their capital expenditure from the budgeted level. Among the states reviewed, the ones set to miss their deficit targets for the current fiscal by the widest margins are Bihar and West Bengal.

Andhra Pradesh, clamouring for a special-category-state status and resultant higher transfers from the Centre, has done badly; so have Rajasthan and Telangana.

While Karnataka and Maharashtra have also failed to meet the deficit targets for the year, their deficits remain below the 3% threshold.

In the case of Chattisgarh, Kerala and Madhya Pradesh, the targets are being met, but their deficit levels are higher than 3%. Among the good performers are Gujarat, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, which all have met the respective targets and kept the deficit levels below 3%. Tamil Nadu too brought down the deficit considerably – from 4.1% in FY17 to 2.8% in FY18 – but only after a sharp 21% capex cut.

Outperforming the Centre, Indian states had achieved creditable fiscal consolidation till FY12 (when their combined deficit stood at 1.93% of the GDP), but have since turned less prudent; the combined deficit widened to 2.69% in FY15 and the UDAY scheme for power discoms extended the fiscal gap to 3.03% in FY16 and further, to 3.67% in FY17 (UDAY allowed extra fiscal headroom to a maximum of 0.5% over and above the normal FRMB limit of 3% for FY16 and FY17). As the UDAY burden was set to largely removed in FY18, the states targeted aggressive deficit cuts for the year, but it now appears that the planned consolidation did not occur.

On its part, the Centre is missing the fiscal deficit target of 3.2% for this year by 30 basis points even after cutting capex by 12%. The next financial year being an election year, it has an uphill task when it comes to achieving fiscal consolidation.

The fiscal slippages of the Centre and states have mostly to do with less than the projected revenue. Although revenue spending hasn’t been curbed much in most cases, capex has been a casualty. PSUs and other government agencies have stepped in to keep public capex somewhat robust.

Though the GST revenue is set to pick up, there are clouds on the states’ fiscal outlook for FY19. This is because farm loan waivers (six states have already announced largesse to farmers and more may follow suit) will be spread over mainly FY18 and FY19 and pay hikes are likely to have an adverse impact on FY19 state budgets.

Bihar’s high fiscal deficit is on account of increase in both capex and revenue expenditure while its “own revenue” remained static at just a third of Central government transfers. Andhra Pradesh, which lost out major sources of revenue due to bifurcation of the state, exceeded FY18 deficit target by 60 basis point to accommodate more capital as well as revenue spending as it builds infrastructure. West Bengal will miss fiscal deficit target by 105 basis points as it has now reset the aim at 3% for FY18 from earlier estimate of 1.95%. The Central transfers (tax devolution and grants) to West Bengal are 50% more than the state’s own revenues in FY18, indicating poor revenue raising capacity of the state.

The Centre are states are shifting to a fiscal road map where overall debt reduction will have a principal role. In the latest Budget, the Centre reiterated its commitment for a revised fiscal glide path, and adopted the Debt Rule recommended by the FRBM Committee headed by NK Singh. The panel had suggested a ceiling for general government debt (both Centre and states) of 60% of GDP by 2022-23 from 73% in FY17. And within this overall limit, a ceiling of 40% is proposed for the Centre and 20% for the states.