By Ashok Gulati and Purvi Thangaraj

At the Hiroshima Summit 2023, the G7 nations (the US, the UK, Germany, Italy, Japan, France, and Canada) stressed on achieving a global Green House Gas (GHG) emissions peak by 2025. They also committed to an “Acceleration Agenda,” for G7 countries to reach net-zero emissions by around 2040 and urged emerging economies to do so by around 2050. China has committed to ‘net zero’ by 2060 and India by 2070.

However, the emerging trends of climate change may not give humanity the luxury of time. Severe costs are likely to be inflicted on human lives and livelihoods, especially in the agriculture sector, with every 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature compared to pre-industrial levels. India has the largest workforce (45.6% in 2021-22) engaged in agriculture amongst all G-20 countries. Hence, the impact of climate change may be disproportionately harsher for India.

Also read: Beating plastic pollution

The urgency for accelerated climate action rose as the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) forecast that global near-surface temperatures are likely to increase by 1.1°C to 1.8°C annually from 2023 to 2027. It also anticipates that temperatures will exceed 1.5°C for at least one year within this period. According to the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), India experienced its fifth-hottest year on record in 2022, with an average land surface air temperature 0.51°C higher than the long-term average over 1981 to 2010, while global temperatures were around 1.15°C higher than the average over 1850-1900.

It is against this backdrop that Indian agriculture faces a double whammy. On the one hand, it has to feed the largest population (1.42 billion in 2023 and likely to be 1.67 billion by 2050), and, on the other, it has to do so against rising vagaries of nature. While India’s grain production (330 million tonnes in 2022-23) gives some comfort, its nutritional challenge remains daunting till 2030.

How can Indian policy makers address this? The answer lies in focusing on Agricultural Research, Development, Education and Extension (ARDE). Research at ICRIER indicates that investing in agri-R&D yields much greater returns (Rs 11.2) compared to every rupee spent on fertiliser subsidy (Rs 0.88), power subsidy (Rs 0.79), education (Rs 0.97), or roads (Rs 1.10). Thus, increased emphasis on ARDE can help achieve higher agricultural production in the face of climate change.

ARDE is critical in improving resource-use efficiency, especially with respect to natural resources such as soil, water, and air. Development of seeds that are more heat resistance is already a reality. Precision agriculture, such as drip irrigation, can result in large water savings. Implementing sensor-based irrigation systems, for example, enables automated control. Fertigation and development of nano-fertilisers can help save not only on the fertiliser-subsidy front but also improve the carbon footprint. Implementing such innovative farming practices and/or products can surely help use water and other natural resources more efficiently, resulting in higher output with fewer inputs, while lowering GHG emissions. Research at Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA) clearly shows that mulching not only contributes to higher soil organic carbon (SOC) but also saves water and reduces GHG emissions.

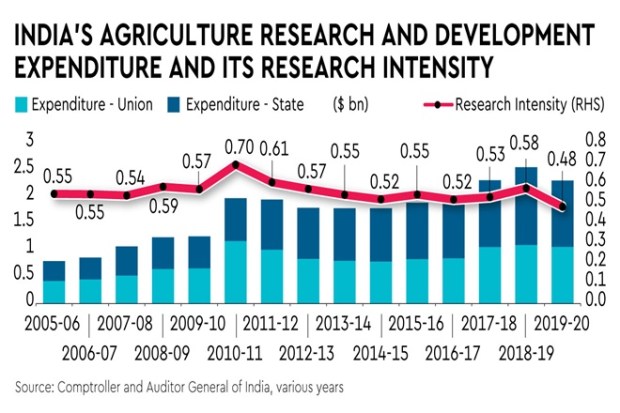

Scaling up such pilot experiments is critical for wider, more sustainable impact, and that is where one needs larger allocations of funds for agri-R&D. Our analysis of ARDE spends since 2005-06 reveals that although, in absolute terms, the total expenditure has increased from Rs 39.6 billion ($0.91 billion) in the triennium ending (TE) 2008 to Rs 163 billion ($2.2 billion) in TE 2020, but the research intensity (RI)—ARDE as a percent of agri-GDP—has experienced an upswing from 0.55% in 2005-06 to its peak of 0.70% in 2010-11, before declining to 0.48% in 2019-20 (see graphic).

Also read: Scrap 20% TCS

Upon examining the allocation of ARDE by sector, it becomes evident that there is a skewed distribution towards the crop husbandry sector, whose relative share has marginally increased from 75% to 76% between TE 2008 and TE 2020. In contrast, the shares for soil, water conservation, and forestry sectors have declined from 5% to 2%, while the share for animal husbandry, dairy development, and fisheries have also decreased from 11% to 8% during the same period, despite the share of livestock’s value having substantially increased in the overall value of agri-produce. This imbalance needs urgent correction, especially because much of the GHG emissions (54%) within agriculture comes from the livestock sector.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that despite the expenditures on ARDE, the overall RI in agriculture falls short of the target of ‘1% of the Agricultural Gross Value Added (AGVA)’ recommended by the government of India’s as well as the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). To accomplish this, India needs to almost double its budgetary allocations for ARDE. In this context, If the Union government can reduce its fertiliser subsidy and state governments their power subsidy, and those savings are redirected to agri-R&D ensuring RI at 1% at the very least, the results would be much better in terms of food and nutritional security. But this requires political will and innovative policies ensuring that farmers incomes go up during this realignment phase.

Along with substantial increase in the budgets for ARDE, one needs to realign not just expenditures but also policies (such as fertiliser subsidy, power subsidy, etc) towards meeting the challenge of climate change. It may be noted that livestock has been growing at more than double the rates of growth of cereals, and so is the case with horticulture. But our policies and programmes are stuck with the legacy of basic staples like rice and wheat. This needs to change to give us better nutrition and less GHG emissions.

Writers are respectively, distinguished professor, and research associate, ICRIER

Views are personal