By Ajay Chhibber

In 1968, the Nobel Prize winning economist Gunnar Myrdal wrote Asian Drama: An Enquiry Into the Poverty of Nations, a pessimistic analysis of the prospects of economic development in South Asia—and extended it to include Burma (Myanmar), Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. He referred to them as “soft” states incapable of organising the wherewithal for proper governance. His analysis initially appeared prescient, and helped him win the Nobel Prize in Economics as well. But, as events have unfolded, it has been proven excessively pessimistic and fatalistic. Now, a new Asian drama is being played out in the region. The battle for poverty eradication, and sustainable human development is by no means over, and could get more intense in the next decade.

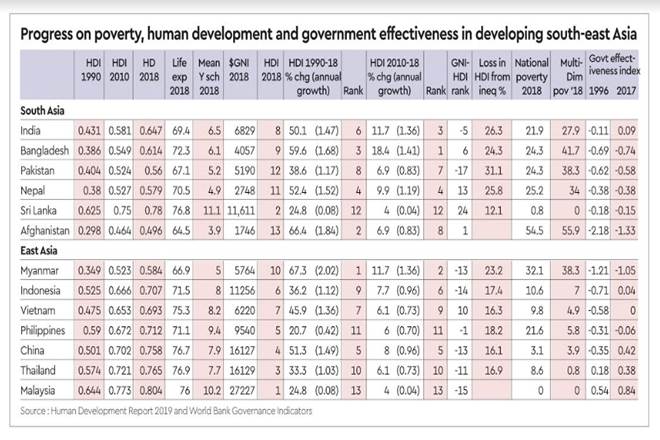

In South Asia, extreme poverty, defined by the World Bank as income below $1.9 per day at 2011 prices, has dropped from 47% in 1990 to under 10% in 2018, and is likely to reach well below 5% by 2030. This is, no doubt, a remarkable achievement. But, the battle is not yet over as other measures of poverty—the national poverty line—show around 25% of the people are still living in poverty. And, the new multi-dimensional poverty index produced at Oxford University in collaboration with UNDP—this looks at people’s access to housing, sanitation, water, and their health and education, and not their income—shows that around a third of the population of South Asia remains deprived of these basics.

But, what cannot be denied is that over the last 30 years, South Asia has seen huge improvements in income—Gross National Income (GNI)—reduced poverty, and witnessed increases in life expectancy and education, as measured by the World Bank Governance Indicators, despite generally ineffective government institutions. This progress is very well captured by UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI), created by two notable South Asian economists—Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, and Mahbub-ul-Haq—around 1990, with equal weights given to income, life expectancy, and education. Between 1990 and 2018, the most rapid increase in the HDI was in Myanmar (over 67%), followed by Afghanistan (66%), and Bangladesh (60%), albeit from a low base and despite weak government institutions and effectiveness—as shown by the World Bank’s Government Effectiveness Index.

The two largest Asian economies, China and India, also saw huge improvements in their HDI—both above 50%. Nepal, squeezed between the two Asian giants, has done even better, with its HDI growing 52.4% from 1990 to 2018 despite slow growth in GDP , weak government, and periods of civil war. Remittances have helped increase its GNI, and focus on healthcare (declining infant and maternal mortality) has helped increase life expectancy above 70 years. Sri Lanka has seen the slowest increase in HDI in South Asia—although from very high absolute levels. The civil war, and less effective government in Sri Lanka has clearly held back its progress. But, with peace restored , and with high levels of education and healthcare, Sri Lanka can hopefully get back to faster growth and improve its HDI towards levels seen in the developed world.

India has made quite steady progress in its HDI, with a slight slowdown in the last decade. Within India, 10 states—Kerala, Goa, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Haryana, Maharashtra , Manipur, and Mizoram—with a combined population of 320 million, have a high HDI. Kerala, with a population larger than Malaysia’s, has similar HDI, and does better than Thailand or Sri Lanka . But, India’s two most populous states Bihar (population 100 million), and Uttar Pradesh (population 230 million) have the same HDI score as Pakistan (population 204 million), so a lot remains to be done.

While HDI has risen, it has seen a worrisome slowdown in the last decade, especially in countries with still low levels, such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nepal. On the other hand, Bangladesh has not only accelerated its income growth, but has continued to make huge progress in life expectancy due to better healthcare, and a focus on the education of girls. Bangladesh’s progress is also deeply embedded in its community and civil society organisations, despite less effective government.

Pakistan specially, but to some extent India too, must pay much greater attention to health, and education. Their HDI ranks are lower than their GNI ranks—in Pakistan’s case, by as much as 17 positions. Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka have the opposite—their HDI ranks are substantially above their GNI ranks, by 13 and 24 ranks, respectively. In the case of Nepal and Sri Lanka, the focus must be on reviving growth. In general, with the exception of Vietnam, East Asian countries have higher GNI scores than HDI scores. They have also seen substantial improvements in the index of government effectiveness.

Rising inequality poses a substantial hurdle to progress in human development and poverty eradication in South Asia. UNDP’s Human Development Report 2019 provides estimates of the loss in HDI due to inequality, including inequality in access to education, and healthcare. Except for Sri Lanka, most South Asian countries are showing substantial losses in HDI due to inequalities. The largest source of inequality in South Asia is access to education whereas in East Asia, it is largely inequality in income. A greater focus on access to education, and on infrastructure will give the biggest returns toward improving HDI in South Asia.

The region has made huge progress on poverty eradication, but must, now, keep its focus on sustainable economic and human development for the next two decades to eliminate poverty, and move its societies into the high human development category of countries. Conflicts, both external and internal, and wasteful spending on armaments will delay progress, and shift attention from a historic phase in South Asia’s development. Divisive internal politics—now more prevalent in the region, as elsewhere in the world—can also derail economic and social progress unnecessarily. More cooperation between countries in the region—open trade, and cross border investment—and ways to address common problems such as the Himalayan Meltdown, rising seas, air and water pollution, and repeat pandemics are the need of the hour to preserve and build on the progress made so far in the fight against poverty.

Climate change—the mother of all market failures—poses the biggest challenge to poverty eradication in South Asia, but is not yet captured in any human development index. According to the World Bank, over 700 million people were affected by climate-linked disasters in South Asia. By 2030, over 60 million in South Asia will fall into poverty due to climate change alone. Rising waters due to increased sea levels, and melting glaciers in the Karakoram-Hindu Kush-Himalayan ranges, which provide sustenance to almost 1.9 billion people in South Asia, and are being depleted rapidly and leading to climate-induced migration. Repeat eruptions of pandemics like Coronavirus show that hygiene and sanitation, and public health need much greater focus.

The stage for the next phase in the Asian drama gets even more challenging, and may well require more effective government that Myrdal felt was missing.

The writer is distinguished visiting scholar, Institute of International Economic Policy, George Washington University, USA. Views are personal.