By Amandeep Chopra

On June 27, 2016, the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, was amended via Finance Act (India), 2016, to constitute the 6-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). This was done to spur transparency and accountability while fixing India’s monetary policy. The amendment structurally set the course for Indian debt markets.

With a “flexible” inflation targeting mandate, it became positive for debt market investors as they could now look at the real rate of returns (nominal returns less average CPI) from their investments in bonds. The market trends since then have reflected this correlation—barring the Covid-19 period, when this relationship was broken. But it has gone back to providing real rates of returns for fixed income investors for short to medium terms.

For global portfolio investors, there is an argument for considering the Indian fixed income markets. A stable monetary policy framework that has been consistent in its objectives is important, as it plugs adverse trends in other important macro variables and maintains domestic financial market stability. It particularly allows the rupee to move in line with its fundamentals.

On comparison with other emerging markets (EMs) on key macros, India fares favourably on the aspects of a stable investment grade rating, strong economic growth, real rates on local currency bonds and an acceptable level of CA deficit. A consistently top quartile growth economy with a benign inflation outlook and a manageable Current Account Deficit (CAD) aids economic and financial market stability.

In terms of size, India is the second-largest bond market among EMs with an exceptional size of $2.15 trillion, next only to China and South Korea in Asia. India also offers a large base of sovereign and investment-grade corporate bonds with a variety of maturities and ratings. This makes India a likely candidate for inclusion in global bond indices.

As the Indian economy grows and aims to be a $5-trillion economy by 2027, the size of its bond markets will continue to grow. This is an investment pie that cannot be ignored.

As seen in countries like Brazil, China, UK, etc, when bankruptcy reforms and processes mature, they help the corporate bond market grow at a faster rate. The bond-to-GDP ratio nearly doubled in the five years of the implementation of bankruptcy reforms in these countries. With the maturity of the resolution process under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) 2016, the risk appetite of investors in bonds rated locally at ‘A and below’ increases and a market for stressed assets and bonds develop.

The rupee has shown movements on both sides (appreciation & depreciation) in the short term against the dollar. However, it has generally followed a depreciation bias over a longer period. Fundamentally, a currency’s relative movement is a function of inflation and interest-rate differentials. While we have always had a positive differential with the US rates, with the inflation differentials narrowing, we can see a much lower rate of rupee depreciation.

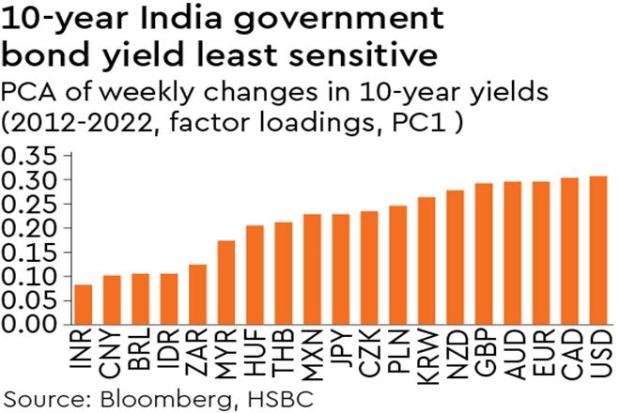

If you exclude the abnormal period of global financial crisis and the taper tantrum, the rupee’s depreciation against the dollar has been at 1.6% over a 20-year period and 3.4% over a 10-year period. The relative volatility of the rupee (vis-a-vis other EM currencies) against the dollar is also relevant. In the popular EM currencies basket, the rupee has shown the least volatility and does well. Historically, rupee yields have also shown lower sensitivity to global rates with a low correlation to US treasury yields.

The combination makes investing in local currency bonds an attractive proposition.

If we were to index the nominal yields of the key EMs by the currency volatility, Indian sovereign bonds offer a favourable relative value. This relationship holds even when we compare the excess carry (measured as the difference of home 10Y benchmark yields with US treasury) over US treasury yields for these EMs.

The outperformance of JP Morgan’s Fully Accessible Route (FAR) Index consists of all Indian sovereign bonds fully accessible to FPIs with broader EM Bond indices where India has no allocation. The benefit of an off-benchmark allocation to rupee bonds in an EM bond portfolio has also been underlined in an HSBC study, which shows that the efficient frontier of the portfolio improves with an allocation to rupee bonds.

A lot of headline coverage and foreign investors’ interest in Indian bonds has remained on index inclusion and a recent study by JP Morgan states that 60% of its respondent want India to be included in the JPM EMBI (The JP Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index).

With a potential $25 billion of expected inflows, the reasons for FPIs to look at Indian bond markets enhancing portfolio performance include: a) stable macro and country rating, b) size and range of instruments, c) low sensitivity of Indian bond yields, and d) the low volatility of the rupee.

The author is Group president & head of fixed income, UTI Asset Management Company Limited

Views are personal

The views expressed here are not investment advice.