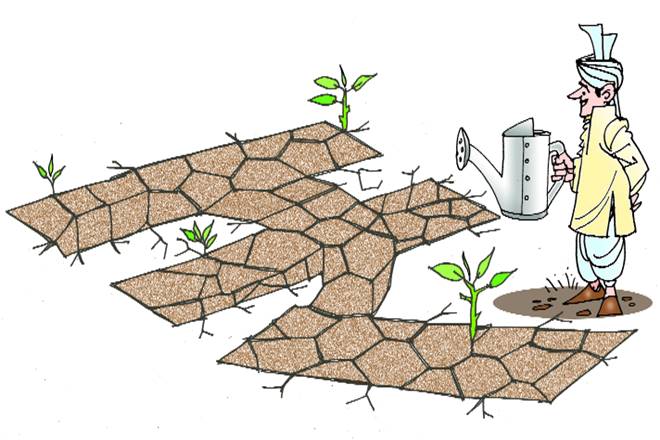

When the new MSP regime was implemented in July, one of the common fears in the market was that the hikes would stoke inflation fears. Four months down the line, not only does this fear seems to have subsided, but serious concerns are now being raised over the continued decline in food prices. Food inflation in rural areas at an all-India level has been consistently declining and stood at 1.9% in FY19 (till November) as against 5.4% in FY15. While such decline/low single-digit inflation in food prices are a boon for consumers, it is bad news for farmers.

Interestingly, one common thread that runs in the states of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, besides the elections that just concluded, is the continuous decline in rural food and beverages prices. For Chhattisgarh, the average decline in food prices in post MSP/Aug-Nov period was 3.3%, for Madhya Pradesh 0.38% and for Rajasthan 2.2%. Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand and Haryana, the major agricultural states which are due for election next year, are also seeing declining food and beverages prices. It now seems that the AASHA procurement scheme has not taken off significantly (agriculture, though, is a state subject), resulting in farmers just not getting remunerative prices for their crops.

A logical corollary of the above is debt waivers for farmers that have now been promised in all the states where elections recently concluded. Several states have already announced loan waivers, taking the total of loan waiver to `1.2 lakh crore since 2017—the implementation of this is still underway. Among the states which are due for election next year, Andhra Pradesh, Haryana and Odisha, have a fair share of agri credit. Even if these states individually announce debt relief, the incremental debt waiver over and above Rs 1.2 lakh crore could be a frightening figure.

However, such waivers are not the solution as they are a drag on credit discipline. Our analysis of agri-NPAs (as % of agriculture advances) for the Sep’18, Jun’18 and Mar’18 quarters for select banks revealed that almost all the major banks have registered increase in agri-NPAs in Sep’18 or are at the same level as Jun’18 quarter. It is most likely that such figures might stay elevated in the Q3FY19, as loan waivers have been promised in three of the five states where elections were held recently. Our fear is that, if a remedy is not found quickly, waivers will continue to be the order of the day in most of the states going to elections in 2019.

We believe there are several options to tackle the problem upfront, particularly through several variants of income support scheme (ISS). An ISS has obvious fiscal implications, but a debt waiver too has this, and ISS is far better than a waiver that might not reach deserving farmers. Let us discuss these variants one by one.

First, let us consider an income support scheme for small and marginal farmers across India. Our estimates suggest that there are around 21.6 crore small and marginal farmers (or 4.3 crore families). We can provide an income support of Rs 12,000 per year (Rs 1,000 per month) per family of small and marginal farmers, apart from other programmes. This could cost around Rs 50,000 crore per year.

Second, a closer look at agricultural growth in Q2 reveals that the growth of 3.8% was mostly driven by “livestock, forestry and fisheries” components (6.7% growth). On the other hand, the crop segment, which also includes fruits and vegetables, and has a weightage of 45% in overall agriculture, has grown by a mere 0.5%—this indicates agriculture as a profession has been losing its importance because its incentive structure.

India is endowed with the largest livestock population in the world. Thus, if the livestock rearing is taken up professionally, this would not only result in increase in income but would also work as risk diversification. To help boost livestock income of the farming community, boosting the demand for milk is key. This can be done by, among other things, providing it as a part of mid-day meals for school-children at the pan-India level. This will provide additional income of `7,000 per annum for 1.58 crore farmers and make livestock rearing an attractive proposition, particularly for small and marginal farmers. The total cost to the government could be around Rs 11,000 crore in the process.

Third, emulate the Telangana government that is already implementing a scheme (Rythu Bandhu) under which 58.33 lakh farmers in the state get a support of `4,000 per acre per season. Telangana has made an allocation of `12,000 crore for this scheme in its FY19 budget. As per our estimates, this scheme, if implemented at the pan-India level, could cost around `2.7 lakh crore (for all states, based on net sown area). Thus, it cannot be tried as an option at the pan-India level given the huge fiscal implications. However, our analysis reveals that it may be rolled out in states like Bihar, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Punjab, Jharkhand and Uttarakhand where the cost is not prohibitive.

We all know that better marketing for the produce and efficient supply chain management can help minimise the stress in the agri-sector. To aid the farmers, the government has already started promoting Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) that work as a hybrid between a cooperative and a private limited company. They act as sub-agents for government agencies in procuring agri-commodities for their members under various government schemes and simultaneously undertake organised marketing on their behalf.

For those obsessed with the fiscal deficit numbers, there are ways to mobilise this additional cost, but for now, an income support scheme is what is needed.