By Ashok Gulati and Purvi Thangaraj

Let us start with some good news. As per the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the monsoon rainfall momentum has picked up, and the overall deficiency of rainfall in June (1-29) has reduced to 5 % compared to its Long Period Average (LPA). IMD has also predicted that July rainfall will be normal and so would be overall rainfall for the monsoon season (June to September). The sowing of important kharif crops, especially rice, maize, millets, pulses, and cotton, is likely to pick up speed. That will give much-needed relief to agriculturists and the observers of agriculture and food prices.

However, the spread of rainfall so far has been quite uneven. Large parts of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala, Telangana, Coastal Andhra, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Bihar, and even West Bengal are still reeling under rain deficiency of more than 20% . This is somewhat worrying.

On top of this, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO)’s report of July 4 has already declared 2023 to be an El Nino year with 90% probability. July 3and 4 have also been reported to be hottest days on this planet. Fast warming of the Pacific Ocean in July-September can play spoilsport for Indian monsoon. One only hopes that a positive Indian Ocean Dipole can neutralise the impact of El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and India can escape a drought.

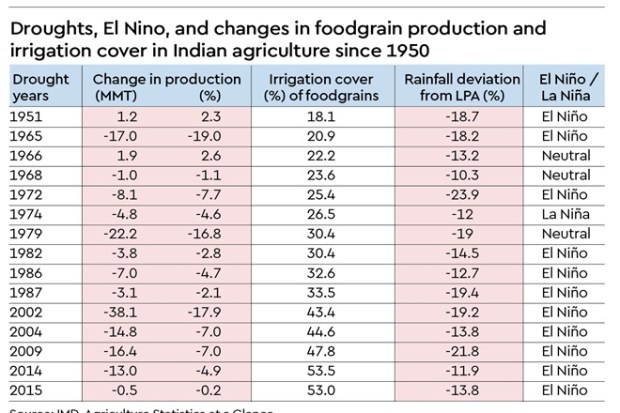

But, what is the relation between El Nino and Indian droughts? How much damage can this do to Indian agricultural production and, thus, food prices? If we look at the Indian rainfall data from 1950 to 2022, there have been 15 drought years when weighted all-India rainfall is deficient by at least 10% of its LPA. Out of these 15 drought years, 11 coincided with El Nino occurrence (see graphic), suggesting a strong correlation between El Nino and Indian droughts; but all El Nino years have not necessarily resulted in droughts. So far, IMD has maintained that despite El Nino, India will have a normal rainfall. We wish IMD’s weather modelling is right. But as old wisdom suggests, hope for the best but be prepared for the worst.We have looked at a scenario if there was a drought or below normal rainfall, how much foodgrain production is likely to suffer and therefore what pre-emptive policy measures can be taken.

It may be noted from the table that droughts of 1965, 1979, and 2002 have been the most damaging ones in terms of drop in foodgrain production in percentage terms over previous years. But the 2002 drought saw the maximum drop in absolute amount of 38 million tonnes (mt). However, the subsequent droughts have been much milder. For example, the 2014 drought led to a drop of only 13mt of foodgrain production, which was just 4.9% over the previous year. The extent of damage obviously depends on the intensity of drought. But as irrigation cover for foodgrains has been increasing over years, from 18%in 1951 to 53%in 2015, it can provide some resilience to foodgrain production against droughts.

On the policy front, the government has been already proactive on taming food prices. Wheat exports have been banned and now stocking limits have also been imposed on traders and processors. Rice exports have attracted export duty of 20% (on common rice). Most of pulses have also been placed under export controls and stocking limits. Lately, the government has also been undertaking open market operations in wheat and rice with a view to bring down cereal inflation, which is still hovering in double digits.

However, some of the vegetable prices are getting totally out of control. Tomatoes, ginger, chillies are making the housewives angry. It seems that the government’s “Operation Green”, which started off with Tomatoes, Onions and Potatoes (TOP) and later on extended to other vegetables, has not tamed prices of TOP. It needs a revisit, and our research in this area suggests that it needs to be taken out of the ambit of ministry of food processing and entrusted with an independent body with a clear mandate to stabilise the TOP value chains, somewhat akin to the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) in case of milk.

But in the case of cereals and pulses, we suggest market operations for rice can be increased till the new crop comes in the market. There are ample stocks of rice with the Food Corporation of India, way above the buffer stock norms. But for wheat, the government needs to hold on to the reserves and perhaps do the open market operations during November-March, when demand will be peaking. Import duties on wheat need to be reduced from 40% to say 10% to augment supplies. Trade estimates of wheat production are much lower than the government estimate of 112 mt. In the case of pulses, especially yellow pea, import duty needs to be reduced to just 10%. We can hope these measures can help contain foodgrain prices.

Writers are respectively, distinguished professor, and research associate, ICRIER

Views are personal