By Renu Kohli

The rupee has been under depreciation pressure since October 2024 despite the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) large-scale forex market interventions. Foreign exchange reserves fell sharply by $79 billion to $626 billion by January 10, 2025, from a peak of $705 billion on September 27. While part of this could be valuation loss, November 2024 data confirms the interventions were quite significant. The central bank sold $29.5 billion (net) in the spot market and an additional $44 billion in the forward market (maturity up to three months) in October-November. As on November 30, 2024, the outstanding net forward market sales position was a historic $58.9-billion high.

These are massive intervention amounts to ensure an orderly depreciation. It has prompted many economists and market analysts to believe the RBI’s interventions have been excessive, and a more appropriate policy should be to allow greater rupee flexibility for absorbing external pressures and avoid overvaluation vis-à-vis many competitor currencies that have been depreciating in response to the hardening US dollar.

We are not sure if that was a fair assessment of the RBI’s interventions. One must acknowledge that until September 2024, the central bank was mostly containing appreciation pressures, not depreciation. This was critical to replenish FX reserves sold during the pandemic. Lessons from past episodes suggest it would not have been wiser to let the rupee appreciate during phases of surplus capital inflows that often result in a wider current account deficit (CAD) followed by a sharper exchange rate correction.

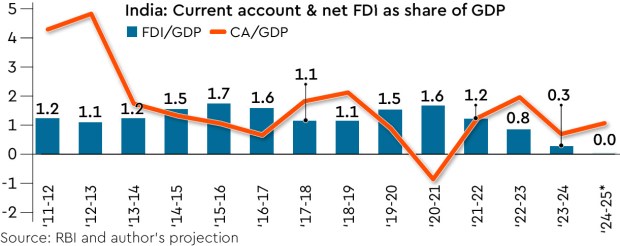

Moreover, if CAD financing has remained moderate for the past several quarters and projected under 1% of GDP in FY25, the case for a sharper and quicker correction in the rupee is debatable. To the contrary, if the forex market pressure originated from sudden capital outflow, a more gradual adjustment would be more appropriate. While a more flexible exchange rate policy is desirable, the focus should be on the capital account.

Consider its four main financing components, i.e., net foreign portfolio investment (FPI), net foreign direct investment (FDI), external commercial borrowings (ECBs), and non-resident (NRI) deposits. The rupee pressures seemed to have been triggered by sudden FPI outflows of $10.8 billion and $2.4 billion in October-November as the US interest rate rose and the dollar strengthened. This was no novelty as India has withstood several such bouts of volatility in the past. The RBI seemed to have mastered the art of simultaneous interventions in both spot and forward markets to ensure an orderly correction.

So, what could have been different in the current episode? In fact, the central bank has been building up an outstanding net forward sales position from March 2024, and yet the pressure on the rupee did not ease.

The answer possibly lies with other components of the capital account, particularly the slowing inflow of FDI. Net FDI inflow, which fell to a 17-year low of $10 billion in FY24, has worsened this year. During the first eight months (April-November), net FDI inflow aggregated just $478 million, largely because of net outflow of $7 billion in the last three months (September-November 2024). NRI deposits [FCNR(B) and NR(E)RA], a very stable financing source, also moderated to $740 million in October with net outflow of $38 million in November. Net ECB inflow too has been quite low recently, a monthly average of $600 million to September 2024. While we do not have data for October-November 2024, there was risk this too could have weakened further because of the dollar’s rise and rupee volatility.

Thus, the financing gap would have been much bigger than the RBI’s currency managers had bargained for!

The RBI is likely to roll back its forwards market position and minimise its spot market intervention for a more flexible rupee. Unfortunately, though, that may be a necessary condition but not a sufficient one. A weaker rupee is no guarantee to improve the current account balance in the short run. Without any immediate reversal in capital flows, the pressure on the rupee is unlikely to ease as financing a much smaller CAD could prove critical.

Thus, the policy focus must turn to the capital account, specifically reversing the trend of secular decline in net FDI which is turning out to be a double blow — weakening prospects for private investment revival, and shutting off a significant and durable financing source for the current account. In fact, net FDI mostly stayed above 1% of GDP until FY22, after which it has slowed alarmingly from FY24 and fell to negligible amount until November 2024. If the trend persists in the forthcoming months, the pressure on the rupee can only mount (see chart).

Can ECBs and NRI deposits fill the gap? Most unlikely. Both respond to interest and exchange rate movements. Although the RBI has raised the interest rate cap on various tenures of NRI deposits in December, exchange rate volatility could be a deterrent. And with mounting rupee pressure, corporates would likely delay borrowing plans until the exchange rate stabilises.

Thus, in the short run, the only hope is that FPIs return. That appears difficult. After a small $3-billion inflow in December, FPIs have sold nearly $8 billion this month so far. It is striking that the total FPI sell-off, $19 billion since October 2024, is from the equity market — perhaps reflecting weak corporate results. There has been very little movement in the debt market, neither buying nor selling, despite hardening US interest rates. Although one must flag that FPIs have mostly stayed away from India’s bond market post-inclusion in the JPMorgan bond index.

The situation remains fluid, and possibly macro-critical. One will have to see if the RBI will be able to assert monetary policy independence and lower the policy rate in February, risking a debt market sell-off and further pressurising the rupee. Likewise, any deviation from the fiscal consolidation path could unnerve the bond market. And to believe external sector pressure could be relieved through a more flexible exchange rate is somewhat misplaced. For a durable rupee stability, policy must address structural issues to make India an attractive destination for FDI again.

The writer is senior fellow, Centre for Social & Economic Progress (CSEP), New Delhi.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of FinancialExpress.com. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.