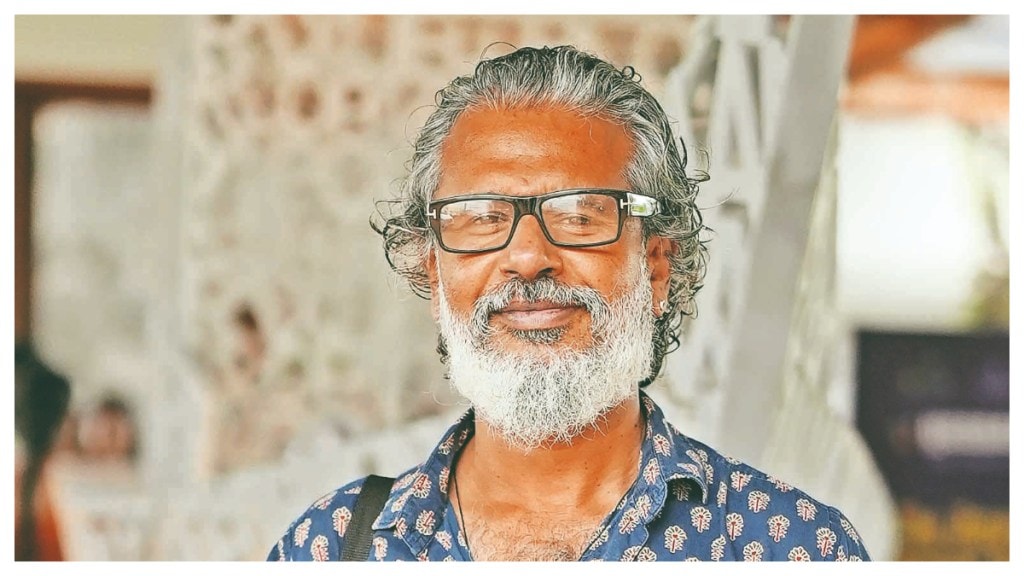

Much has changed in the subcontinent since Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka won the Booker Prize for his second novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, in 2022. His country witnessed protests by the people and got a new government last year. There have been changes in the neighbourhood too, in Bangladesh and Nepal. The political changes have coincided with the rise of literature in South Asia, including global awards for both writings in English and translations from local languages. Karunatilaka, a regular speaker at literary festivals in India, was at the first Yaanam travel literature festival in Varkala, Kerala (October 17-19), to talk about his literary journey. The writer speaks with Faizal Khan about the increasing international gaze on literature from the subcontinent, the Aragalaya movement in Sri Lanka and his new projects. Edited excerpts:

What are the major factors that have contributed to the rise of South Asian literature in the past half-a-decade or so?

We certainly have had a golden age of Sri Lankan writing, and for Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian as well. One reason is there are many diverse stories in South Asia, ranging from absurd to tragic. For my parents’ generation, writing wasn’t a viable career. But when Salman Rushdie won the Booker Prize for Midnight’s Children, that opened doors for many of us. I remember that in the Sixties and Seventies, Sri Lankan writing in English sounded like an Englishman’s.

They were all trying to be Englishmen trying to write like Ernest Hemingway or EM Forster. But after Midnight’s Children, realisation hit that we can not only tell our story, but tell it in our own voice too. Then in the Nineties, there was Rohinton Mistry, Arundhati Roy… who inspired us to start writing. Today, there are a lot of writers developing their craft. Now we are not shy to write about ourselves, to use our own voice… There was never a Sri Lankan section in a bookshop when I was growing up. Now there is a whole Sri Lanka section with everything—thrillers, and science fiction, and award winners. We have stories and we are not afraid of our own voices. And we’re inspired by others who have done it before.

What about the depth of writing in Tamil and Sinhalese in Sri Lanka today?

We have a rich tradition of Sinhalese literature going back centuries. And obviously Tamil writing in India and in Sri Lanka. But these are in silos. Then you have the Colombo, Galle and Kandy writers like myself writing in English and we don’t read each other. There’s probably resentment because the English writers only get published abroad and get fame. But the Sinhalese and Tamil writers, they are rockstars in Sri Lanka. You go to the book fair and those are the guys who are getting the readers. But it’s in silos. Now I’m pushing myself to read Sinhalese books and I’m learning Tamil. Now we also have a generation of translators coming up. I think global tastes have also changed. I think people are a bit sick of reading about Europe. When I watch Netflix or the likes, I am watching a Spanish comedy or a Korean horror movie or a Tamil movie.

How is the current international gaze on writers like you who have won major international awards by reclaiming the narrative?

I think there is more interest now in Sri Lankan writing than there was, say, 30 years back. But do we need the international gaze? You’ve got more than a billion people in India. We have more than 20 million in Sri Lanka. We can just fight for ourselves. I mean, Bollywood doesn’t need to win an Oscar; it’s doing better than Hollywood. Maybe we should just write for ourselves. What happens when you write for yourself? Suddenly, it becomes authentic and people are interested. When you try and think, what is London going to think, what is New York going to think about this, you lose your authenticity and the book’s not going to be successful. There are still a lot of marginalised writers who maybe don’t have access to literary agents, publishers and industry. But I hope that the fact that I can sit in Colombo and write a book and it gets translated into Bulgarian, is inspiring for a kid who’s now starting to write and thinks that that’s a possibility.

What about life after the Booker Prize?

Three years after the Booker Prize, I’m still talking about it. It has travelled to many countries. I’ve travelled behind it. I was in Bulgaria, it is doing well in Korea, Argentina. The translation rights have been sold in 36 languages, but the next book is not going to write itself. I still have to put in the effort and write the next one.

What is it about Sri Lanka and science fiction, as many Sri Lankan science fiction writers are getting international recognition?

We have got some great writers. Vajra Chandrasekara, who won the Nebula Award in 2023, and Yudhanjaya Wijeratne, who was nominated for the prize. There is Amanda Jayatissa, who is writing psychological thrillers. In the science fiction genre, the writers are getting big publishing deals. I don’t know, maybe it’s the Clarke Club, because Arthur C Clarke was inspiring to me. His 2001: A Space Odyssey was written next door in Colombo 7 (residential district where Clarke lived for four decades). He never left Sri Lanka. There is a science fiction tradition in Sri Lanka, which is good.

There was the Aragalaya movement in Sri Lanka in the same year you won the Booker Prize. How is the people’s struggle changing the country and impacting society?

I don’t know. I write historical fiction. I’ll tell you in ten years, because Sri Lanka has been through enough turmoil. We had dictatorship, we had democracy, we had terror attacks, we had the protest movement, we had economic collapse, and now the JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna), who were getting killed in The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida. Those guys are now in power. I don’t do takes on current affairs. That’s why I’m not a journalist. So I can’t say.

But I do know that society is a lot more. Muslims, Tamils, Hindus, Buddhists, Christians—they were all looking out for each other. It was a very wonderful moment for a country that’s had so much conflicts. So I think the new generation is not as cynical as us. We were Generation X, we thought the world was never going to change. But these kids demand better. The two main political parties were completely annihilated in the elections. The NPP (National People’s Power) is in power now. People want new ideas. I think it’s a positive thing. The kids believe they can change things, which is a good thing. There’s optimism.

What is your next book going to be about?

I’m doing some children’s books. I do have a third novel and a fourth novel that I have researched and I’m ready to write. I can’t tell you about it because it’s bad luck to talk about books that you haven’t written because you’ll never write them. But I’ll say it is set in Sri Lanka. And it’s got no cricket, it’s got no ghosts.

Faizal Khan is a freelancer