Who cares if Mahar lives or dies,” says a policeman in Marathi writer Shankarrao Kharat’s novel, Taral Antaral, a stinging critique of atrocities against Dalits first published in 1981. Based on Kharat’s own life as a member of the Dalit Mahar community in Maharashtra, Taral Antaral was a rude awakening for readers who were suddenly presented with a new anti-caste language in Marathi literature.

A close associate of BR Ambedkar, Kharat was one of the earliest voices in Marathi literature championing class and caste struggle with his powerful novels and short stories. More than four decades later, literary works in Indian languages about people living on the fringes of society are more visible across the country, thanks to resilient modern publishing practices that embrace diversity in translation.

There is a curious anecdote about Kharat and Ambedkar mentioned in the literature on caste and struggles by Ashoka University’s Centre for Translation, which aims to translate material from many Indian languages into many other Indian languages. It talks about a conversation between Ambedkar and Kharat. According to writer and poet Yogesh Maitreya, Ambedkar is heard telling Kharat: “We have doctors, engineers, lawyers, and many educated people in our community but we don’t have writers. Our community’s literature needs to be established all over India. You must take on this responsibility.” Adds Maitreya, “That moment led to the birth of a writer in Shankarrao Kharat. Since then, Kharat has been unstoppable, writing six novels, eight short story collections, an autobiography, and several non-fiction books—all focused on the issues important to the Dalits’ struggle.”

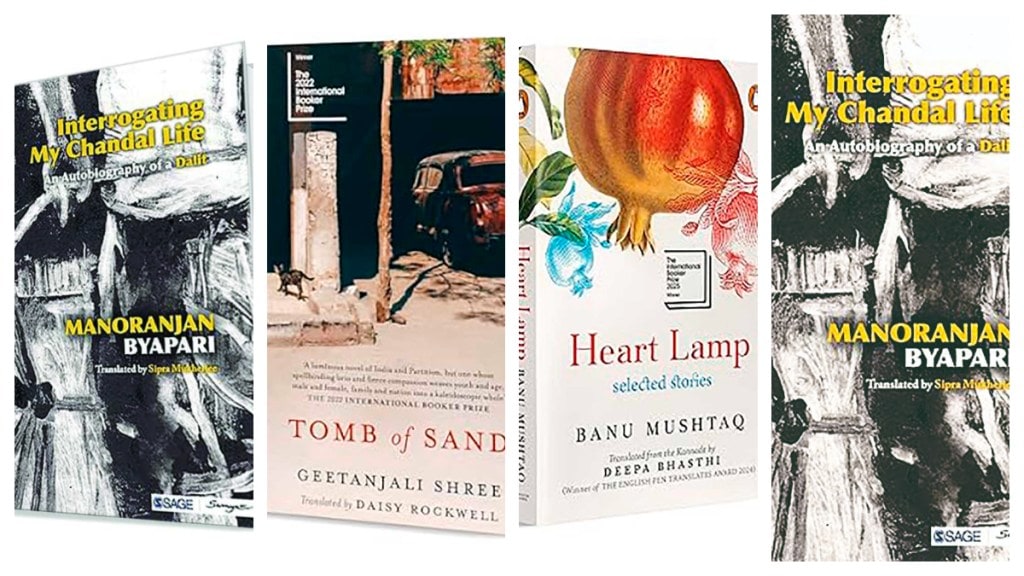

Struggles by Dalit and minorities and gender justice have catapulted to the centre of book lists by both independent and mainstream publishing houses, making fiction and non-fiction available to readers in different Indian languages today. In the past three years, two Indian books in translations, one a rare window into the lives and dreams of Muslim women, Heart Lamp: Selected Stories by Kannada writer Banu Mushtaq and translated by Deepa Bhasthi, have won the prestigious International Booker Prize for translations into English. Mushtaq and Bhasthi’s win followed the first International Booker Prize for an Indian book, Hindi writer Geetanjali Shree’s 2018 novel Ret Samadhi (Tomb of Sand) three years ago.

Echoes from society

“Many more books in Indian languages dealing with Dalit struggles, minority experiences and gender justice are getting translated across languages and into English today,” says Bengali author and Dalit activist and leader Manoranjan Byapari. “This is a direct response to the social struggles on the ground demanding justice and equality,” adds Byapari, the author of such powerful novels drawing from his own experiences as Itibritte Chandal Jivan (How I Became a Writer: An Autobiography of a Dalit) and Thik Thikaanar Sandhaaney (The Nemesis). “Twenty years ago I never thought I would be published. Today it is imperative that Dalit writings are part of the social discourse,” says Byapari, a former chairperson of the Bangla Dalit Sahitya Academy.

Among the titles translated into Bengali by the Jadavpur University Press in the past five years are Amar Babar Bagan (My Father’s Garden) and Adibasira Nachbe Na (The Adivasi Will Not Dance), both by Santhal writer Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar. “We publish significant scholarly works on women and marginalised communities,” says Jadavpur University Press editor Suchismita Ghosh, who translated My Father’s Garden from English to Bengali. The Adivasi Will Not Dance, Shekhar’s collection of short stories published in 2015, deals with the Santhal community through searing tales of arranged marriage, sex workers, migrant workers and domestic workers.

“Recently, one has noticed that the voices which were earlier on the margins are being brought by mainstream publishing houses. Stories of the women, Dalits, and tribal communities are being written, translated and even taught at universities,” says poet and translator Saba Mahmood Bashir. “The voices which were earlier barely written, or overshadowed by other voices are finally being heard,” adds Bashir, whose forthcoming book, Darkness and Other Stories, is a translation of 11 selected short stories of Urdu writer Razia Sajjad Zaheer.

“Razia Sajjad Zaheer, who won the Nehru Award in 1966 and Uttar Pradesh State Sahitya Akademi Award more than half-a-century ago, has surprisingly never been translated into English before. One finds only a couple of her stories in anthologies but not a single book in English translation,” says Bashir.

Published by Zubaan Books, an independent feminist publishing house, Darkness And Other Stories is one of 12 books in languages like Tamil, Bangla, Hindi, Sindhi and Urdu translated into English and across languages by the Ashoka University’s Centre for Translation in partnership with Zubaan Books in a two-year-project. The project, Women Translating Women, supported by the Susham Bedi Memorial Fund, include Guptodhon by Bengali writer Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay translated into English by Ipsa Samaddar, Karai Thedum Odangal by Ramachandran Usha translated from Tamil by Krupa Ge and Navabhum Ki Ras Katha by the late Hindi poet and writer Susham Bedi translated from Hindi by Astri Ghosh. “Susham Bedi’s writings reflect the negotiations of identity a migrant faces in the meeting with a new world,” explains Ghosh.

Year of translation

Launched three years ago, the Centre for Translation at the Ashoka University hosted a national conference on translations, Bhashavaad, at the India International Centre in Delhi from August 29-30 to continue its aim to bridge languages, preserve cultural richness and ensure that voices from across India could be heard and understood more wisely.

“Complicated questions are entering the world of translations,” says writer Urvashi Butalia, co-founder of India’s first feminist publishing house, Kali for Women, and founder of Zubaan Books. “Representation carries with it a huge responsibility,” adds Butalia, one of the speakers at a session, Writing Women, Translating Women, at the conference.

Echoes linguist and writer Peggy Mohan, “We are standing at a luminous moment in India where translation is beginning to connect us. For the first time, the demand is coming from the public, people who don’t feel completely happy reading in English but know important conversations are happening and want to join them.”

“Indeed, it’s a special moment where translation is being demanded and not thrust upon people,” says Mohan, the keynote speaker at Bhashavaad, adding: “In fact, I am getting a strong feeling that this year is the year of translation.”

Faizal Khan is a freelancer