By Mohit Hira

It has been said the life of a founder is a lonely one. And clichéd as it may sound, at the end of a hectic day, founders often seek solace in themselves. Their lives—regardless of whether they succeed entrepreneurially or not—are fraught with challenges that are certain to change a person from deep within.

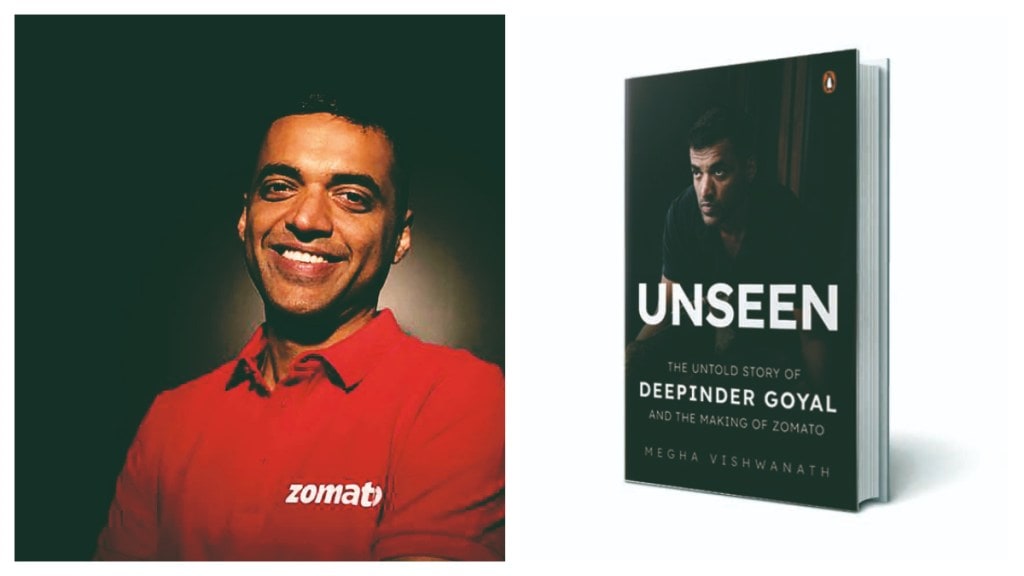

If you read Megha Vishwanath’s biography, Unseen: The Untold Story of Deepinder Goyal and the Making of Zomato, in this context, sections that come across as almost hagiographic—or overtly filled with unabashed admiration—will appear deeply empathetic. The result is a rather linear but meticulously chronicled narrative of the Zomato founder’s journey who is referred to by his pet name Deepi throughout. It spans childhood trauma, parental influence, entrepreneurial ups and downs, and the relentless pursuit of building both a company and himself. Written with a sharp eye for culture and context, the book will be illuminating for Indian readers familiar with Zomato —as customers, startup founders, investors, and aspiring entrepreneurs eager for an unseen view of the making (and almost unmaking) of one of India’s most storied startups.

The opening section of the book is almost cinematic as the author opens with the IPO listing and then flashes back to Deepinder’s childhood, a period shaped as much by familial warmth as by silent emotional struggle: “Muktsar (a small town in Punjab) for Deepi, was not a place of unease but of familiarity, where life moved at its own gentle pace, and fear was an emotion that existed only in stories, never in his reality”. Yet, outside this cocoon, relentless bullying—marked by taunts about his dark skin, short stature, and a stammer—left “wounds, the likes of which take years to heal, if they truly ever do.” These scars, the author insists, were not erased by outward accomplishments: “Some part of me still carries that trauma. When a child is bullied for being different… it etches something deep into their soul.”

Especially poignant is Deepinder’s account of grappling later in life with the discovery of Asperger’s Syndrome—a diagnosis that explained his lifelong sense of otherness and emotional intensity. “Had he spent his entire life fighting a battle he was never meant to win?… knowing why didn’t erase the scars—it only defined them. And sometimes, that’s even harder to accept.” In passages reminiscent of Arjuna on the Mahabharat battlefield, Megha Vishwanath captures these reflections that ground the book in the psychological realities often glossed over in business memoirs.

Throughout Deepinder’s academic journey—from being “labelled ziddi (stubborn) by his family,” to enduring academic comparisons with his brother—his “tenacity, which was a source of frustration in childhood, would later become one of his greatest strengths”. The turning point arrives after a brief bout of cheating in exams, which is dealt with reflectively and honestly: “Success, he realized, didn’t require endless hours of toil—it simply demanded focused effort”. This theme of self-renewal, adaptation, and direct confrontation of weaknesses sprinkled with grit, underpins the entire book. Much like a flawed character in a film, qualities like these enhance relatability.

Zomato itself is portrayed as an “accidental company”, started with a basic need in Bain’s cafeteria—digitising and sharing restaurant menus. The high-pressure decision to leave a “well-paying job” —something many founders have experienced—and the emotional roller-coaster of startup life is captured vividly, with parental anxiety (“with some reluctance, he (Deepinder’s father) and Kaushalya transferred INR 2 lakh to help Deepinder get started. It wasn’t an investment in a business. It was an investment in their son”) lending the narrative a touching, universal and almost Bollywood-like resonance for Indian readers.

One of the book’s most emotionally charged sequences traces the partnership between Deepinder and Pankaj Chaddah from friendship forged in the trenches to a slow, painful drift apart. When Pankaj finally steps down, the narrative is raw: “Trust, he said, had perhaps eroded… Pankaj’s departure shook Deepinder’s self-confidence. He internalized the blame, often believing that the unfolding events were, in some way, his own doing or fault. There had been moments when he could have acted differently, made better choices, prevented the fallout”. The emotional cost of scaling and leading is laid bare: “I’ve never said this out loud, but there were nights I thought we wouldn’t make it. That I wouldn’t make it. But we are still here. And that’s something no one can take from us.”

An important dimension of the book is its context-setting within the broader Indian startup surge. The author references Flipkart’s funding rounds, redBus, InMobi’s pivots, and acquisitions such as HungryZone and Burrp.com. Particularly noteworthy is Zomato’s rivalry with Swiggy and the effects of competition. When Zomato acquired Blinkit, the book details the risks: “Honestly, even in food delivery, we still don’t know how we’ll ever make money”.

If the Blinkit acquisition is considered a feather in Deepinder Goyal’s cap, the failure of taking over Urbanspoon in the US also merits introspection: “…Deepinder got carried away. The visual of painting the world map red with Zomato had a seductive pull… it was purely egotistical and made no rational business sense.” The book does detail several instances where Zomato and its founders experienced significant failures and faced ethical dilemmas including financial mismanagement: Zomato faced a cash crunch when unchecked spending and lack of discipline led to wasteful travel and lavish events. Deepinder implemented drastic reforms, acknowledging, “I was angry at myself for letting it happen. Zomato clearly fell into the classic hyper-growth trap, where speed eclipses structure…”.

While the book is candid in admitting failures, strategic miscalculations, and leadership mistakes, it does not chronicle instances of intentionally compromising on ethics or integrity. Rather, it attributes mistakes to inexperience, overconfidence, and the pressures of crisis management, and highlights a willingness to confront these transparently and learn from them.

And though it also touches upon the journey of founders who moved on, such as Pankaj’s wellness startup Mindhouse, it is the role of early backers such as Sanjeev Bikhchandani, founder of InfoEdge, that are worth dwelling upon. In Sanjeev, Deepinder found not just the earliest and most significant investor, but a sage counsellor bringing both funding and perspective to his journey. A particularly emotional moment is described when Zomato expanded into Deepinder’s hometown, Muktsar. Sanjeev is told over a call: “We’ve launched in Muktsar.” He recognises immediately that this update carries deeper personal significance for Deepinder than a simple milestone, reflecting how investors understood his emotional motivations alongside commercial ones.

What sets this book apart is its close examination of leadership and the emotional labour required. Deepinder’s struggles with communication—stemming from childhood stammer and later adult anxieties—surface during Zomato’s IPO: “His words, he feared, wouldn’t arrive on time. They would get stuck. It would be quite embarrassing for me to do these conference calls. All I would do is stammer. I’d rather write”. The coping mechanism of writing shareholder letters instead of calls—“explaining Zomato’s strategy with utmost candour and clarity” —shows a founder finding his voice on his own terms.

The author does not shy away from the cultural breakdowns within Zomato either; whether it is the “cultural debt” that can make a startup brittle or the power paradox: “We rise in power and make a difference… but we fall from power due to what is worst. Our influence is… only as good as what others think of us”. Deepinder’s attempts to effect renewal, listen to “corridor conversations,” and promote action over hierarchy —these are highlighted as essential founder lessons.

Writing a biography such as this is anything but easy. While the author’s tone is generally sympathetic to Deepinder’s emotional struggles and his relentless drive, she takes care to avoid pure idolisation—the failures, inter-personal conflicts, and personal limitations are given fair space. For instance, Deepinder’s role in founder fallouts is acknowledged, and leadership missteps are not glossed over. Yet, the book undeniably reads as a kind of tribute, not in the sense of uncritical adulation, but more as a celebration of vulnerability and earnestness in leadership. The author’s narrative occasionally tilts toward making Deepinder’s strengths appear heroic.

For any startup founder, investor, aspiring entrepreneurs still in college or cocooned in the comfort of a cushy job, and for students of human psychology, there are vital lessons here on a founder’s psyche, his emotional resilience, the importance of culture, and the crucial distinction between accidental success and intentional evolution.

Mohit Hira is co-founder, Myriad Communications, and venture partner at YourNest Capital Advisors