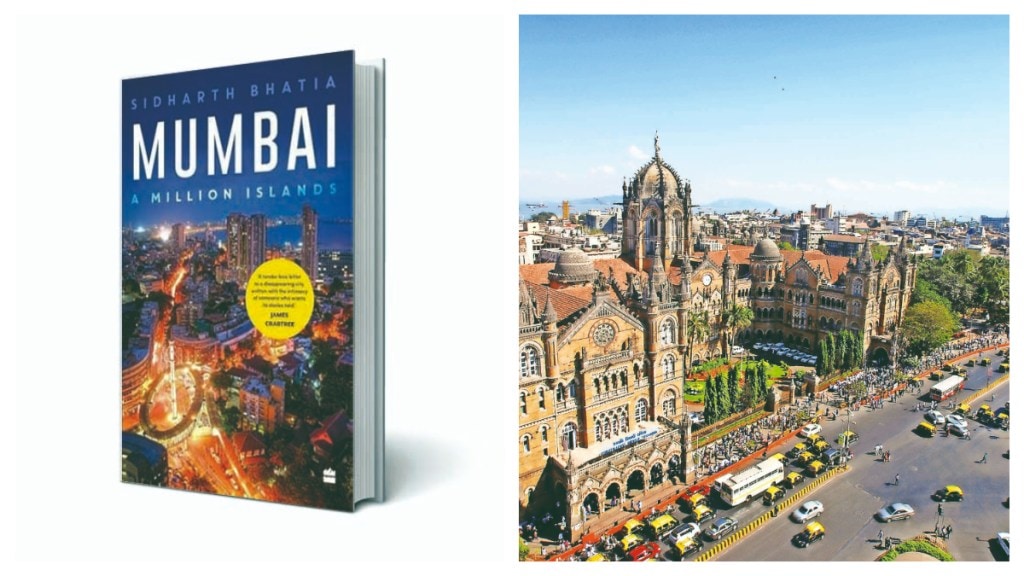

Mumbai is the financial capital of India and probably the biggest attraction for youth looking for a living. But has one stopped to study and observe the city? Delhi as a city has a lot of historical significance, which has been brought into focus extensively through literature and art. But that kind of attention is missing for Mumbai. It is here that Sidharth Bhatia makes a mark with his brilliant book, Mumbai: A Million Islands.

The ‘million islands’ suffix is interesting as this a narrative about various sights in the city. Mumbai is endless in terms of the stories that can be told, and this holds true for its culture as well. The history of the city is not just of a homogenous entity, but that of several islands which shape what the city is today.

Balancing the present with the past, the author gives the reader a feel of both simultaneously as we turn the pages. Several thought-provoking points are made by the author in the book. For instance, he starts off by talking of ‘Mumbai is upgrading’, which is something one sees in the construction work of bridges, coastal roads and metro lines all across the city, something that is a continuous process. These have been pain points for citizens who have borne the brunt for years. There is a distinct tilt towards the rich, the author conveys, as seen by the luxury residential complexes that have come up, or the ostentatious structures in Bandra Kurla Complex.

Read FE 2026 Money Playbook: Your Ultimate Investment Guide for the new year

Upgrading Paradox

The author also talks of the evolution of areas dominated by the Muslim community and portrays their fears and inhibitions. Contrary to conventional wisdom, parents in this community want their children to get an English education, hoping for upward mobility. There has been significant ghettoisation because of the community living in the same areas for decades and which looks distinctly underdeveloped compared with other geographies. A major challenge for Muslims is to find accommodation because of the prejudices that have been ingrained among the city as a whole. And this holds irrespective of one being a commoner or a celebrity. The author talks to people in these communities and there is some recollection of the infamous Mumbai riots, during which they were at the receiving end.

Written in a very conversational form, Bhatia explores Mumbai through chapters dedicated to its various localities. The one on south Mumbai is classic as he delves into how British presence brought about a westernised look. The area of Marine Drive and Colaba carry a lot of history, and the author particularly talks of the architecture of these places. Houses had limited spaces for lobbies and took one directly to the lift unlike what we see today where vanity precedes everything else. There is commonality in the architecture in most buildings constructed at that time which is interesting. In fact, reading the book, the reader is compelled to go to Marine Drive and see for herself this distinct trait. Similarly, when he describes the walls around these buildings as being low and how the buildings ‘talk’ to those on the road reads very poetic.

He also takes us through the historical context of some of the dining places in Mumbai and starts with their foundation in the early twentieth century and their genesis. Liquor was not permitted in those early days and one needed a permit for it. Dress codes were a norm, and these hotels could get risqué with cabarets leaving nothing to imagination.

Bhatia describes his own escapades when talking to developers who are looking to create homes for the ultra-rich, resulting in buildings scaling heights both in terms of structure and price. Several areas in Mumbai now have been converted into major construction sites not just because of the metro but also for re-construction. Yet, something seems unplanned when one looks at how focus has shifted from Nariman Point and Reclamation in south Mumbai to Bandra Kurla Complex, which today is a nightmare for everyone as entry and exit to the place are challenging. Those who depend on public transport struggle to find one, while those with their own vehicles are left frustrated in their quest to park and exit.

There are 11 chapters capturing such images of the city, and while it is evidently not comprehensive, the book does cover most of what was known as Mumbai to begin with. The chapter on ship breaking and slums takes us thorough the property of Mumbai Port Trust and its evolution or neglect. The one on ‘Mills Become Malls’ is a must read for the present generation which is only aware of the high-end premium shops with high snob value and gourmet dining, and which excludes the proletariat through their pricing. These spaces were mostly textile mills with a history. Bhatia takes us through the trade union movement in this context and the story of its annihilation.

‘The Hidden City’ is the last chapter which will make us think harder. Starting from RK Studios, which was earlier known for glamour, he takes us through an area called Deonar and beyond. There are 124 five-storey buildings in the area that one will not notice. It was never advertised but was constructed by the famous builders like Hiranandani and the Shahs. These were rehabilitation buildings where one resident had just 225 square feet of living space. In the author’s words, which are eloquent and soul searching: “All of these buildings look like a vertical slum, a brutalist creation like council estates elsewhere. Add to it the fact that it is in the back of beyond, and the sense of alienation and exclusion is complete.” This is very hard-hitting considering that all this re-construction is otherwise considered as upgrading the city of Mumbai!