A pop song is supposed to behave like milk. It is meant to spoil, to curdle into nostalgia, to get archived as a guilty pleasure you admit to only after two drinks. “Jimmy Jimmy Aaja Aaja” does not follow those rules. It keeps resurfacing like a stubborn buoy, bright and unbothered.

In 2023, it turned up again in a new body, when the Korean artist Aoora released a K-Pop version with Saregama, reintroducing that chorus to audiences who were not even alive when Disco Dancer first made it travel.

The hook stayed intact, the moves got updated, and the internet did what it always does with things that feel familiar but newly packaged. It replayed it until the familiarity became new again.

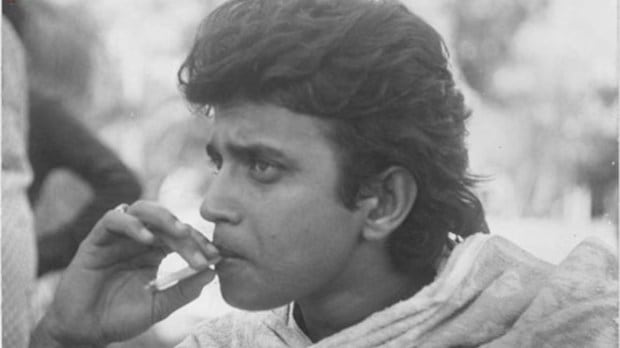

Millions of views and thousands of comments later, I don’t think there can be any other cultural event better than this as an entry point to the legacy of Mithun Chakraborty.

This moment captures the core truth about him. Mithun is not a man you can keep inside one era. He keeps earning attention even when he is not in the frame. And in the business of entertainment, attention is not a soft thing. It is the raw material that keeps turning into cheques, fees, leverage, and longevity.

People like to pin a single number on a life like his, because numbers feel like closure. The Economic Times has pegged his net worth at around Rs 400 crore, a number neat enough to fit a headline and dramatic enough to travel faster than nuance ever does.

But celebrity wealth rarely arrives as a single, clean total you can circle in red. It accumulates the way a long career accumulates: in layers, in assets, in businesses, in property that quietly appreciates, in fees that rise and fall, in brand value that keeps finding new buyers.

He has been dismissed and rebranded more times than the industry can count. At various points, he has been written off as “gareebon ka Amitabh Bachchan”, shamed for his skin colour, treated like a low budget punchline, then quietly welcomed back as a National Award winning actor again, and finally stamped as legacy with national honours.

He built a career on being saleable across territories and decades, he worked at a scale most actors cannot sustain, and then he did the crucial conversion: he turned volatile film income into infrastructure, especially hospitality, the sort of cash-generating engine that does not care whether the reviews are kind.

To understand why he built that way, you have to go back to his origin story and the first time Mumbai made him bargain for dignity.

From Gouranga to Mithun Chakraborty

He was born on July 16, 1950, as Gouranga Chakraborty. He studied at Kolkata’s Scottish Church College and grew up in a lower-middle-class Bengali household where money was tight and the decade’s politics were not a distant radio bulletin but something that pressed in from the street.

In the unrest of the 1960s, a young Gouranga was drawn toward the Naxalite movement and became an active participant in it. Then his brother met with an accident, and the tragedy yanked him out of that world. He stepped away, believing the chapter was closed.

It was not. The tag stayed attached to him, long after he had tried to leave it behind, moving toward cinema, long after he was attempting to be seen as only an actor in the making.

As he told veteran film journalist Ali Peter John, “People in the industry and outside it knew all about my involvement with the Naxalite movement in Calcutta and my close links with Charu Mazumdar, the fiery leader of the Naxalites. I had quit the movement after there was a tragedy in my family, but the label of being a Naxalite moved with me wherever I went, whether it was the FTII in Pune or when I came to Mumbai in the late seventies.”

The Naxalite tag that followed him everywhere

FTII did not erase his Naxalite past, but it gave him a new language for it, a new discipline, and a new identity that could finally outrun the old label. Mithun Chakraborty, as we know him today, was born to the film industry.

Mrinal Sen met Mithun during an acting class at the institute. The legendary filmmaker was working on his next film, Mrigayaa, and was casting for the lead of the film – Ghinua – a tribal hunter, and by most accounts he had struggled to find the right kind of physicality for the part.

He wanted someone who could play a tribal hunter but could not find one and then happened upon Mithun during a teaching session at FTII. Mithun had been working out and was physically in shape to play the part.

Sen cast him in Mrigayaa, and Mithun did something almost rude in its rarity. He won the National Film Award for Best Actor for his debut. That kind of credential is supposed to change your address. It is supposed to end the conversation. You can almost imagine the young man thinking, now they have to take me seriously. But Mumbai did not care.

The Mumbai bathroom that cost a membership

Mumbai makes you pay for basics in strange currencies. For Mithun, the bill was dignity. He has spoken about those early years without romance, “I have seen days when I had to sleep with an empty stomach, and I used to cry myself to sleep. In fact, there were days when I had to think about what my next meal will be, and where I will go to sleep. I have also slept on the footpath for a lot of days,” he said recalling his hardships on the singing reality show Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Li’l Champs.

A friend arranged a Matunga Gymkhana membership so he could use the bathroom in the morning. Not a room. Not a bed. Not even a dependable meal. A sink and a mirror and a few minutes of water, so he could walk into offices for auditions, looking like a man who belonged there.

The “Gareebon Ka Amitabh” insult

And then there was the second humiliation, the one the industry practises even today while pretending it is not policy. Colour. He has spoken about being shamed for his skin tone and dismissed as “gareebon ka Amitabh Bachchan,” and not considered an acceptable hero.

“In fact, I was even prepared to play negative roles because my confidence was shattered by a certain section of people who would discourage me for my looks,” he told Stardust in an interview in 2006.

Journalist Ali Peter John’s writing captures the same era with an even starker image, he asked Mithun for an interview, and Mithun asked for a thaali in return because he had not eaten for three days.

It sounds theatrical until you remember the kind of poverty that teaches you to price your words against hunger. That is the early Mithun equation in one exchange: talent on one side, survival on the other, and a young man learning, brutally fast, that an interview was not just a conversation, it was a currency, which could come back as a plate of food.

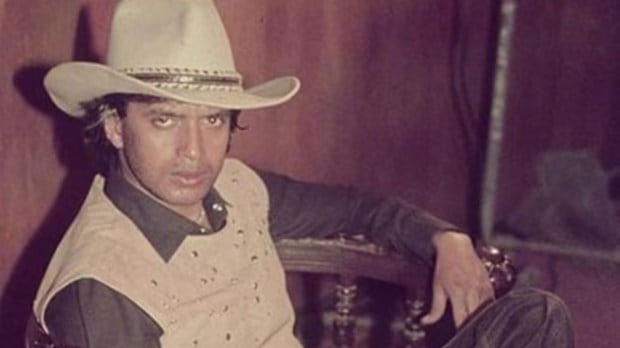

In order to break through Mithun even changed his identity to Rana Rez for a brief time and joined Helen’s group as a backup dancer. She was so impressed with his skills that she once offered him a 30-minute spot that made the audience swoon.

He had to be a great actor to be a star, but his dancing skills provided him an edge that other heroes of the time didn’t have.

Zeenat Aman and the Jinx Breaking “Yes”

Every outsider needs one high status, yes. One person who stands next to you and tells the room you are safe to touch. The Indian Express notes that at a crucial stage, Zeenat Aman agreed to star opposite him in Taqdeer. Mithun credits her with breaking the jinx. Once the number one heroine said yes, others followed.

This is how stardom actually scales in Mumbai. Not with merit alone. With endorsement by proximity. One powerful ally changes the market’s risk perception. Mithun goes from being a bet nobody wants to place to being a bet everyone wants to claim they saw early.

The eighties arrived like a Mithun invasion. Surakshaa. Dance Dance. Pyar Jhukta Nahin. Commando. And the movie which changed Mithun’s life – Disco Dancer – the first Hindi film to cross the ₹100 Crore barrier.

The movie didn’t just give rise to the “sexy bengali babu,” not only in India, but also in the Soviet Union, where the movie sold over 120 million tickets. Audiences came for the dance numbers, yes, but they kept coming back because the whole package was addictive: the beat, the shine, and Mithun’s body moving in a way Hindi cinema had not quite seen before.

It is also a film that is unapologetically of its time. Not timeless, not subtle, just very 1980s. The audiences forgave the absurdity of the film’s storyline because it was delivering something rarer – a near music video experience in a country that did not yet have music videos as a constant diet.

If you wanted that kind of kinetic, repeatable, song led high, you went back to the theatre again and again and, that is why “Jimmy Jimmy” could travel then, and why it can travel now.

Building a hospitality empire

In the business of films, fame is a Friday to Friday business. Mithun understood that the hard way, and that is why the pivot came early, while the applause was still loud enough to be converted into something permanent.

By the end of 1990, he had incorporated Mithun Hotels Private Limited and anchored the first major bet in Ooty. The Monarch was not built like an actor’s weekend escape. It was conceived like a proper commercial machine: a hundred rooms, large banquet capacity, and restaurant facilities that make sense only if you are planning for volume, weddings, groups, and repeat occupancy. The tell is scale. This was never about a view. It was about a ledger.

From there, his footprint starts reading less like celebrity indulgence and more like serious entrepreneurship. Ooty stays the anchor because it gives you climate, tourism, and a steady stream of people who want the hills without effort. Masinagudi adds the experience layer through a safari park. Mysuru becomes the heritage stop, Bengaluru expands the logic into business real estate and, Siliguri pushes the brand toward the North East gateway. Each location is doing the same quiet job: building demand that does not depend on box office mood.

For context of what these investments mean, ICRA expects premium hotels to hold 72 to 74 percent occupancy in FY 2026, with average room rates at Rs 8,200 to Rs 8,500, and operating margins for large hotel companies in the 34 to 36 percent range. That is what makes ownership matter more than noise.

In hill destinations like Ooty, the second engine is the land itself. Housing.com trend data puts the average quoted price in Ooty around Rs 10,696 per sq ft, with localities like Lovedale shown at Rs 14,318 per sq ft in the same tracker. Add the wider hill station appetite, where a Business Standard report, says quoted prices across major hill destinations rose 10.3 percent year on year, and you can see how a hotel portfolio starts behaving like a compounding asset, not just an operating business.

It wasn’t a surprise then that between 1995 to 1999 it was Mithun Chakraborty not Amitabh Bachchan who was the highest taxpayer in the country. But Mithun wasn’t only satisfied being a businessman. He was creating a whole new film industry of his own.

The thirty-three flop film wonder!

By the late 90s, the mainstream film industry had a neat little joke it liked to tell about Mithun: too many films, too many costumes, too many flops. The numbers were brutal. Depending on who is counting, it is thirty or thirty three flops over a few years, enough to bury most careers under polite silence.

And yet he was somehow busier than ever, signing film after film as if box office failure was an opinion, not a verdict. That is the first clue that he was no longer operating inside the Mumbai definition of success.

Mithun was operating inside a parallel film industry that sat within the mainstream and fed off a different audience, a provincial and small town India that did not need critics and did not treat a multiplex review as a moral instruction.

In that market, the film only needs to feel like value for money. That audience shows up, week after week, because the transaction is not about taste, it is about reliability. According to film trade analyst Komal Nahata, Mithun was minting money in his worst period.

Mithunnomics: How he built a parallel Bollywood in Ooty

Once that formula was set, Mithun industrialised it. He stopped shooting in Mumbai, shifted his base to Ooty, and made geography part of his business model. He would dole out bulk dates to producers in one go, with the caveat the film must be completed within that window. Take it or leave it.

The heroines, mostly there to tick the song and dance box, were interchangeable, often flown in from the South, Rambha, Sneha, that rotating bench of glamour. The film would be wrapped in four months, no drift, no indulgence.

It kept interest from eating the budget alive. And the logic was almost embarrassingly clean: low budgets meant low selling prices, and low selling prices meant the producer was no longer gambling, just doing safe business.

This is where the so-called flops started behaving differently. They stopped being career ending events and started becoming inventory that always returned money.

The real masterstroke was that he did not only sell his face. He sold an entire production ecosystem. Ooty was his base, and he offered sops, the kind that make a producer’s spreadsheet relax its shoulders.

He bought film equipment needed for the shoot and let producers hire it at a discount, so they did not have to carry their world from Mumbai. Senior artistes stayed at his Hotel Monarch at a filmi discount.

You did not just hire Mithun, you rented a ready made factory floor: location, lodging, logistics, gear, schedule, all bundled around a star who would finish the job fast. In that model, even when the films did poorly, distributors rarely lost money because the risk was engineered down at every step.

He had become more than just a star, he was a bankable businessman actor, who had built wealth around himself, and he lived like it too, in bungalows, in assets, in a private world big enough to shelter almost a hundred dogs.

Sixteen bungalows, seventy plus dogs, and the emotional shape of wealth

By the time you reach the late act of the Mithun story, the punchline has quietly become the proof. The same man who once priced an interview as currency for a plate of food now has The Economic Times estimating his wealth at around Rs 400 crore.

You can argue about the precision of that figure, because celebrity money always arrives as fog, not as an audited closure, but the shape of the life makes the fog believable.

Decades of being saleable across territories, then the crucial conversion into hospitality and real estate, then the parallel film factory in Ooty that made even “flops” behave like recoverable product. This is not luck. This is a system. And systems, unlike stardom, do not retire.

The reported details are almost too on the nose, which is why they land. Several bungalows- sixteen in Masinagudi and eighteen in Mysuru- if you go by the way how financial profiles now describe his asset base, the kind of property sprawl that reads less like vanity and more like a man building doors nobody can shut on him again.

And then the softer counter image that makes the wealth feel human instead of cold. The dogs. Not one or two, but a household that has spoken openly about living with over seventy, each with a name, each with a routine, each dependent on the same consistency he once lacked. That is the emotional full circle.

The footpath boy did not just become a superstar. He became a bankable businessman actor who built safety into architecture, and then used that safety to shelter other lives too.

That is why “Jimmy Jimmy” keeps returning. Not nostalgia, not irony, not meme culture. A reminder that Mithun is not an era. He is a machine that learned how to protect itself.

—-

If you want to keep reading, here are some more money trail stories from Bollywood Billionaires, each about a different kind of wealth and a different kind of survival.

Sonam Kapoor is the modern version of inherited advantage done intelligently, where the real play is not “acting fees” but brand equity, fashion capital, and the kind of cultural positioning that turns visibility into a long runway of deals.

Mohanlal is the quiet math of longevity, where superstardom becomes infrastructure, the Gulf becomes both audience and asset geography, and the smartest moves are the ones that do not need loud announcements.

Danny Denzongpa is the blueprint for disciplined wealth, a man who built a fortune by doing fewer things, doing them better, and treating his career like a risk manual instead of a romance.

And Abhishek Bachchan is what it looks like when a famous surname stops being a safety net and becomes a business platform, with investments and brand plays that reveal a different kind of ambition than the one the gossip pages like to sell.

Ankit Gupta has spent almost two decades working with India Today, NDTV and Times Internet. He is a senior creative lead at Hook Media Network within the RP Sanjiv Goenka Group. He writes on the business of entertainment, fashion and lifestyle, bringing a producer mindset to reporting and analysis.