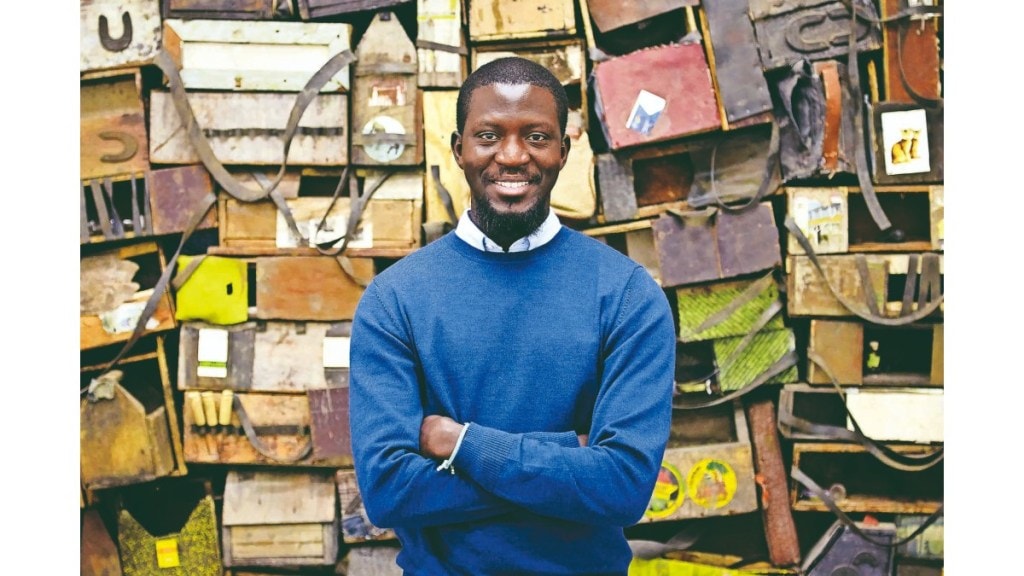

Named the most influential artist in the world, Ghana’s Ibrahim Mahama felt at home in Fort Kochi, Kerala’s heritage town with a history of centuries of colonisation like his own country in West Africa. A participating artist at this year’s Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Mahama collected discarded chairs and jute sacks and repaired them for his installation, Parliament of Ghosts. Mahama speaks with Faizal Khan about the need for a Global South solidarity to navigate socio-economic and political crises confronting the world and his own art practice that puts people at the centre. Edited excerpts from an interview:

1. You have just been named the most influential artist in the world. Were you surprised by the recognition for an African artist for the first time?

I don’t think it is about me. I think it is somehow reflected in the conditions that produced the math. It’s like I am from the Global South and the fact that if attention is paid to these areas, there will be other artists like me who would emerge in the future. I think it’s also an opportunity for people to pay much closer attention to what is happening in the Global South, India included.

2. Is this your first visit to India?

I did come to India in 2018 for a wedding in Agra. I didn’t come to India again until the Kochi-Muziris Biennale this year. I will be visiting India again in February next year for the India Art Fair in Delhi.

Read FE 2026 Money Playbook: Your Ultimate Investment Guide for the new year

3. What is the artistic philosophy and labour behind your installation?

The whole point of the work was to address the question of repair, on a material level, but also on an ideological and historical level. We thought it was quite fantastic to somehow use this parliamentary body as the starting point to rethink what it means for us to focus on the post residues of these material forms. What does it mean to reconstitute them together? And how do they speak to one another?

4. What is the significance of these objects like the discarded chairs and jute sacks?

I like the idea that there are objects which ordinarily might be broken, discarded, thrown away, but in our context and case, we are somehow trying to focus on the inherent value of memory within these subjects, and we are trying by reconstituting them and saving them. We are allowing a much more collective response to these objects. A collective response in the sense that it allows for a lot of people to be able to go back and relate to these objects. Like the furniture in Kochi. A lot of people see them and they’re like, oh, wow, look, I remember this chair from here, there. It allows for a sense of collective reflection. So, for me, I think that when something is declared dead or something like that, it can be discarded. And we, as practitioners, artists, we save it. We all share in the history of that, but someone has to take the responsibility. Art allows us to exercise a sense of responsibility.

5. You once made the material for an artwork in London in a football stadium in Ghana, not inside a studio.

Yes. It was called the Ali Muhammad sports stadium, named after one of our vice presidents who passed away a couple of years ago. I’ve always been looking at the idea of an artist’s studio and what it can do. For me the studio is not just a closed place where artists are supposed to make paintings and sculptures. Everywhere in the world can be the studio— the marketplace, the stadium, the railway station, the bridge, everywhere. When I was a student, I used to go to the market to produce my work there and also to work with the people in the market. I like the idea that we could stretch the meaning and the boundaries of what a space is and what it could apply, artistically.

6. You mentioned stretching the meaning and the boundaries of an artist’s studio. You are doing many things in that direction in Ghana.

Yes, the Red Clay, my studio, was basically the idea of opening up the possibility of experiencing culture in different ways. I’m really interested in what culture has to offer to any given society. Also new and old. I try to focus on the new because I think that children, if they are close to culture and its complexity from different angles, it allows them to develop a bit more empathy towards the world. A lot of people come to my studio for the first time to see contemporary art. They might be composed of objects or things that they know, but they don’t know which way. That’s the beauty about art, that art, in its true sense, always allows for an expansion of freedom, of freedom that we know, that freedom and democracy is not fixed. You know, there’s so much tension within art itself. The studio allows the public to rethink their position when it comes to thinking about art and the freedoms that allow it.