For someone ruminating on mortality since his early youth, Vajpayee met his maker at a rather overripe ninety-three. A stroke eleven years earlier, in August 2007, had taken away his most precious gift: his voice. He recovered for a while, but the battalion of maladies new and old caught up. Sixty SPG commandos divided three shifts between them to guard his life, though there was not much of a life to be guarded. It was a difference of the pulse beating and the pulse not beating anymore. He did not die, year after year, though one could not quite say he lived. Atal Behari Vajpayee had quietly passed on from politics into history.

The Decline and Reinvention

When he exited the scene in late 2008, his Bharatiya Janata Party was consistently failing to gather the emotional and organizational cohesion needed to make a grab for power. The BJP was beset with warring factions, resulting in intrigues which at their meanest meant destroying a rival’s career by releasing a sex CD of theirs. At least two full-timers of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh — the BJP’s ideological fountainhead — were in the dock for plotting terrorist attacks.

This was also a time when the needle of social justice, ever so slow, acquired pace. India got its first minority prime minister, its first woman president; a Dalit woman swept in a majority in the country’s most populous state — a state that had served as the ground for most Hindutva battles. No one seemed to desperately miss the BJP. Some progressive columns derided its swift descent into irrelevance, along with an occasional well-meaning, if no less absurdly exaggerated, speculation of a Dalit march on Delhi.

Vajpayee forgot the world, though the world did not entirely forget him. The Liberhan Commission released its report in 2009, putting the sting in by naming him as one of the ‘pseudo-moderates’ whose ‘sins of omission’ had razed the Babri Masjid in 1992. The following year, the Niira Radia tapes revealed his son-in-law to be a small-time operator in the gossip-business circuit.

Modi’s Rise

Around this time something flipped. Convinced that the forecasts of its irreversible decline were misleading, the grand old party returned to the olden days of complacency and arrogance, miring itself in one high-profile corruption scandal after the other. In India, with its layers atop layers of deprivation and inequality and greed, corruption may be as old as the civilization. Presently, though, the BJP-RSS, desperate to seize the window of opportunity, quietly stoked a faux-Gandhian anticorruption movement.

They ditched L. K. Advani as the prime ministerial candidate. In September 2013, after a sordid drama lasting weeks, the BJP-RSS gifted a wildcard entry to a man manoeuvring from 1,000 kilometres away. While at the 7, Race Course Road, Vajpayee had unsuccessfully tried to sack Narendra Modi, the chief minister of Gujarat, for the 2002 riots there; and pointedly blamed him after the 2004 general elections fiasco.

During the years Vajpayee stayed comatose — or turned into ‘a vegetable’, as the rare hater put it — Modi reinvented himself as an efficient, business-friendly administrator. He hired an American PR firm to rebrand his image. He improved his speech delivery; his facial skin radiated a new glow; his hairline, receding for a while, returned in a firm V-shape. The 2014 campaign pitch ‘Abki Baar Modi Sarkar’ was a riff on the old ‘Abki Baari Atal Behari’. Modi inverted the class condescension flung at him by the liberals and instead channelled India’s aspirational impulses. The party scored its first majority. Old-timers who had been knocked out in this pursuit since their days in the Jan Sangh — the BJP’s forerunner — scarcely believed their luck.

In the run-up, Congress was caught utterly clueless on tackling the torrent of propaganda unleashed by the BJP-RSS. Its leader Rahul Gandhi, for years presented by the media as a most eligible bachelor, was written off as a ‘Pappu’ — an imbecile fifth-generation scion who, far from being eligible for the top executive job, was unfit for any serious career at all. With a rancorous Right pushing itself into power, and the contrast Modi represented, the BJP’s haters turned nostalgic about Vajpayee. His career was suddenly cast into a favourable light by all sides. The bitter disgust that the RSS hawks once felt for Vajpayee had gradually settled into a respectful loathing.

For more than a decade since then, the BJP has commanded the centre and a dozen-odd states, a luxury Vajpayee never enjoyed in his lifetime. Modi has succeeded by blending personal charisma with caste-agnostic populist schemes and a shrewd exploitation of the caste arithmetic in the states. But if he remains invincible within the Sangh Parivar ecosystem, it is also because he has fulfilled nearly all of its decades-old fantasies: a gleaming new Ram temple in Ayodhya; the quashing of Article 370 in Kashmir; early moves to amend the civil laws; and the renaming of towns, roads and buildings after its idols old and new (including a cricket stadium in Ahmedabad named after Modi himself).

There is something deeper at work here. This version of cultural renaissance exerts itself by hammering the basic contract between citizens. It dehumanizes the Muslims, rouses Hindus to avenge the medieval atrocities real and imagined. When citizens are denied a common reality, it turns communities living side by side for centuries incapable of loving or empathizing with their neighbours. A democracy lapses into electoral autocracy of the majority, where nerves are perpetually raw, violence always round the corner. Nehru — who had avidly tracked the rise of ethnic politics in 1930s Europe, and failed to tame the Partition massacres in his early days in office — was prescient in understanding these hazards. In his eyes the RSS didn’t fulfil the basic criteria for democratic deliberation. No wonder the Hindu Right detests him — him alone, among the founding parents of the republic — with such fierce intensity.

***

Once again I attempt to establish that Vajpayee was at the heart of the Sangh Parivar’s project to Hinduize India. The RSS was desperate to capture political power because it understood, accurately, that seizing the state would allow it to mould the body politic to its desire. Vajpayee, for all his grumbling, helped the RSS and its affiliates function as India’s deep nation. In his last public appearance, in 2008, the stroke-battered patriarch allowed himself to be stretchered off to the Parliament House to vote against the Indo-US nuclear deal, whose seeds he had himself sown while in office. I locate him in the larger pantheon of Hindu nationalism, and narrate the story by reflecting him in the mirror of other crucial characters.

With its citizenry overwhelmingly illiterate, India’s democratic broadmindedness was in some ways a top-down imposition. The Congress diluted it over the decades, preparing conditions ripe for the Hindu Right — always lurking in the background — to take over. Vajpayee acted as the crucial bridge, aiding them in using democratic liberties to capture power so they could, when the right moment arrived, stifle the foundations of those very same liberties. Without Vajpayee there would be no Modi.

Excerpted with permission from Pan Macmillan India.

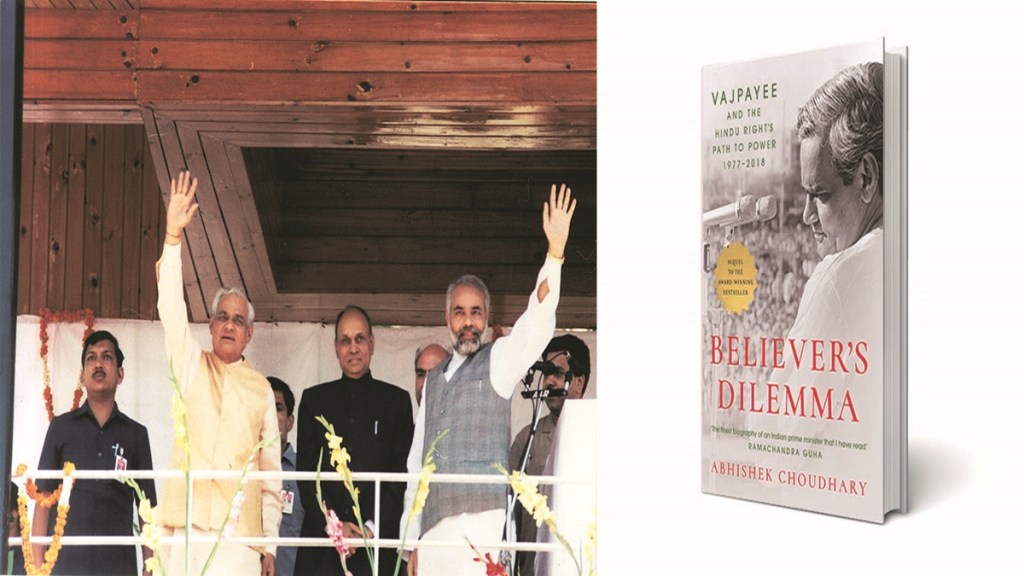

Believer’s Dilemma: Vajpayee and the Hindu Right’s Path to Power 1977–2018

Abhishek Choudhary

Pan Macmillan

Pp 496, Rs 999