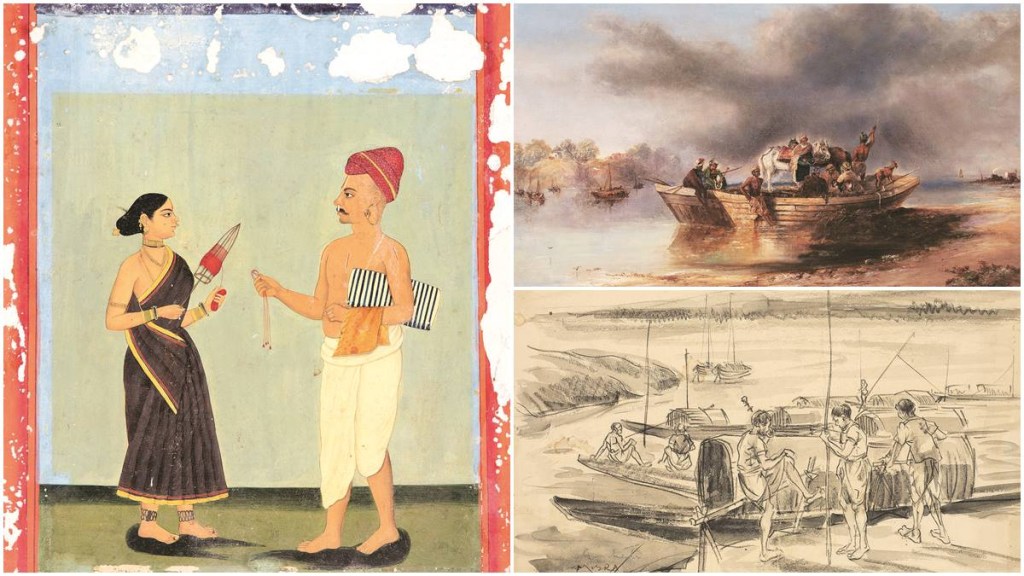

A dhoti and shirt-clad man is holding a sharp-edged metal stylus used for writing on palm leaves. Standing beside him is a woman. The painting from 1770 showing an accountant and his wife portrays the highly-regarded profession of bookkeeping for rich traders during the British Raj. The work of an unidentified artist from Thanjavur, the famous temple city in Tamil Nadu, the painting symbolises the different occupations that functioned within the Indian society under the colonisers.

Part of a new exhibition, March to Freedom, which opened at the Bikaner House in Delhi on October 5, works of art like the 18th-century painting titled, Accountant and Wife, reinterpret the multi-layered aspects of a society that lived and fought for freedom under the domineering British and other colonial powers. The exhibition by independent gallery DAG, which first opened at the Indian Museum in Kolkata during August-September this year to coincide with 75th anniversary of India’s independence, employs art to look back at a turbulent history of subjugation and a valiant struggle for freedom and liberty.

Beyond battles

“March to Freedom reinterprets the well-known story of the Indian freedom struggle and anti-colonial movement through works of art and some historical artefacts,” says historian Mrinalini Venkateswaran, who has curated the exhibition. “Drawn from the collections of DAG, they range from 18th and 19th century European paintings and prints to lesser-known works by Indian artists that merit greater recognition,” adds Venkateswaran, a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Spread across eight sections—Battles for Freedom, The Traffic of Trade, See India, Reclaiming the Past, Exhibit India, From Colonial to National, Shaping the Nation, Independence—the exhibition gathers paintings, prints, drawings, sculpture and film posters to include an expanded theatre of the freedom movement. “Each (section) represents one arena on which the anti-colonial struggle took place, to expand the story beyond politics and battles,” explains Venkateswaran.

Also Read: Love & jihad : A teenage boy’s passion for dance sets the stage for a complicated inquiry into the banalities of belief & everyday life

Mounted in the section, The Traffic of Trade, Accountant and Wife, along with Silk Weaver and Wife (1770), another painting by the unidentified Thanjavur artist, and others such as well-known artist Gobardhan Ash’s untitled 1975 painting—a watercolour on paper—displaying an anchored sailboat connect the colonial history to the elements of commerce that sustained life and economy under imperialism. “Although it is conceived to commemorate and celebrate the 75th anniversary of India’s independence, the exhibition is designed to do more,” explains Venkateswaran, adding: “Even as we remember the struggles, the sacrifices, and the stories, such anniversaries are also occasions for reflection.”

Unsung heroes

The section, Battles for Freedom, that contains paintings by English military illustrators and artists like Henry Martens on the Anglo-Sikh wars during 1845-49 that ended with the annexation of Punjab, places the little-known contributions of tribal communities, farmers and women on the wider canvas of the freedom movement. Besides the First War of Independence in 1857, there were many mutinies across the country that led to the freedom: the Vellore Mutiny of 1806 by Hindu and Muslim soldiers outraged by the ban on wearing beards, traditional turbans and religious marks on foreheads, the Great Santhal Hul (rebellion) of 1855 by tribals from present-day Jharkhand, Bihar and West Bengal, and the Great Kuki Rebellion of 1917 in the Imphal valley against the British attempt to recruit labour for World War I from the hill tribes in the northeast.

The DAG made its entire collection of arts and artefacts available to the curatorial team for the exhibition. “It took about six months to make the basic selection, and another six months to refine it,” says the curator. “The selection was theme-led—so in that sense, I was blind to big names and chose works because of what they allowed me to talk about, and in that way, I was able to include a wider array of artists,” she adds. “We see how the arts as a whole (from painting to cinema), the economy (and the ordinary people driving it), public spaces (and public use of it), colonial institutions (such as courts, museums, and universities), infrastructure (notably the railways), and colonised disciplines (such as history and art history), were all repurposed and reimagined as sites from which to resist colonialism, and shape an independent nation.”

“While the collecting or acquisitions programme is largely eclectic, it is the curators who give the works shape through their ideas and engagements with contemporary issues,” says DAG’s CEO Ashish Anand. “So while DAG has been known for its ‘survey’-style exhibitions in the past, the collection has lent itself to exhibitions that revisit different phases of art practice in the subcontinent as well as ways of seeing that were shaped by Western propaganda, orientalism, or, in this case, the way artists visualised India even as it launched its struggle for freedom,” adds Anand.

“The collection follows a structured theme. More of these works should be seen and understood because time waits for no one and history continues,” says Delhi-based architect Ranesh Ray. “It is very good to see the complicated and challenging history of the subcontinent being presented with many facets of history being explored,” says Jonathan Kennedy, director, arts of British Council in India. March to Freedom follows the independent gallery’s major show, Tipu Sultan: Vision and Distance, held in the national capital in August. Another major exhibition, Drishyakala—a visual narrative of the mood of the nation in the past three centuries at the Red Fort in New Delhi in 2019—and Ghare Baire, on art in Bengal, had heavily borrowed from the DAG’s vast collection of art on India acquired over several decades. March to Freedom runs up to October 28.

Faizal Khan is a freelancer