By Dr Pavan Soni

What’s the single most enduring skill? A skill that was relevant a century ago and would be of consequence at the turn of the next millennium as well? It’s the problem solving skill. Your ability to identify the problems worth solving and then solving them well. How about technology? Will technological advancements, especially the advent of AI, make problem solving less significant? Not necessarily. In fact, technology will, at best, be an aid and not a substitute to one’s skills of being a problem solver. And if at all, technology has always co-existed with us, in the form of pulleys, screws, or the humble pencil. Just that it has assumed a more career threatening posture lately. So, let’s look at how you could maintain your relevance in the hi-tech age where labor displacement is a serious threat.

The way you keep yourself in the game, or rather a step ahead, is by honing your problem solving skills. The World Economic Forum ranks analytical thinking and creative thinking as the most critical skills of the future, much ahead of the more fleeting ones like technology literacy and quality control. I wonder if the stacking order would change in the future. New technologies will keep replacing the dominant ones, but your ability to think through a situation would maintain the highest premium. Technology can help you generate novel and useful ideas, but to identify the problem worth solving would still be for you. It’s only you who can discover, prioritise and articulate the problem of gravitas before you throw it towards technology for possible avenues. And once again, it’s you who gauges how good a solution is, through multiple iterations. That’s how, after all, you teach technology how to think like humans.

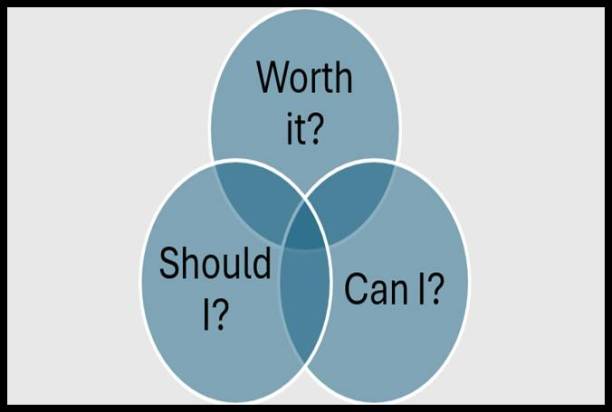

Coming back to problem solving. The critical skill is ‘critical thinking’, your ability to distil the problem to its root and then some more, before arriving at the appropriate response. How do you practice critical thinking, without being critical about people. Let’s invoke a Venn diagram for enlightenment.

So, when you are solving any problem, firstly ask yourself the question: Is the problem worth solving?

How do you know if the problem is worth it? You know it via negativa (the way of negation). You ask the question: What happens if the problem is not solved? And you would discover that the problem that seems very pressing in the present moment diminishes with time, to an extent of insignificance. Very rarely do problem end by becoming as sinister as they seem at first. A good way to ascertain a problem’s gravity is by creating a physical, psychological and temporal distance between you and the problem. For instance, when you see an escalation mail on your phone, your blood pressure jumps and you feel like responding to it immediately. But if only you can buy some time, sleep on the topic, you would not only be able to come up with a better response, but possibly you can choose to not even respond. This choice emerges only once you have put a deliberate gap between the stimulus and your response, and that’s your ‘zone of discretion’, or else you are condemned to be busy with trifles.

Once you decide that the problem is indeed worth solving, the next question is: Should I solve it? Just because the problem is vital doesn’t necessitate your personal involvement. Even for a grievous issue you have three recourses: delegate, escalate, or automate. By delegating you push the problem down the chain of command, giving others a chance to take a stab at it, freeing up your time and energies. By escalating, you elevate the problem and bring it to the notice of higher ups and get vital sponsorship. Finally, you invoke technology wherever possible and automate the task, either within the boundaries of your firm or outside, via outsourcing. In each advent, you free up your bandwidth. The idea is to firstly establish the magnitude and significance of the problem and only then check if it’s worth your while. That is to put a ‘premium on your time’.

Lastly, you must ask the question: Can I do it? If you are convinced that the problem is indeed worth going after, and that you can’t delegate, escalate, or automate, it’s then up to your capability to grind it out. Capability is a rather easy problem to solve—you build it through training and development. But primarily, it must be warranted. If you systematically adopt the stages of Woth it à Should I à Can I, you will realise that there’s not too much on your plate after all.

Now, tell me honestly—what’s your typical first line of attack—worth it, should I, or can I? I reckon most people jump at ‘can I’. They have a go at the problem at the first sight, regardless of whether the problem is worth its while or their suitability. It’s because solving problems is a sure sign of being relevant, being visible and in the thick of things, and many would rather hold on to repetitive tasks instead of graduating to the more significant ones. That calls for honing a strategic mindset and courage.

In summary, just because you can doesn’t mean you should. And that’s how you fend off obsolescence by technology and remain viable in the long haul. Pick important problems and solve them permanently, and wherever possible, exploit technological advancements.

The writer is the bestselling author of the books Design Your Thinking and Design Your Career.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.