By Neel Sarovar Bhavesh

The year 1978, separated by 67 days, saw the birth of two miracle babies, Louise Brown and Durga (Kanupriya Agarwal). Both were the first babies produced using a new medical technology called in vitro fertilisation (IVF), commonly known as test tube babies. Though the description of similar methods has been in ancient Indian textbooks, the birth of both the babies was a break- through in the modern medical sciences that has become a boon for infertile couples globally.

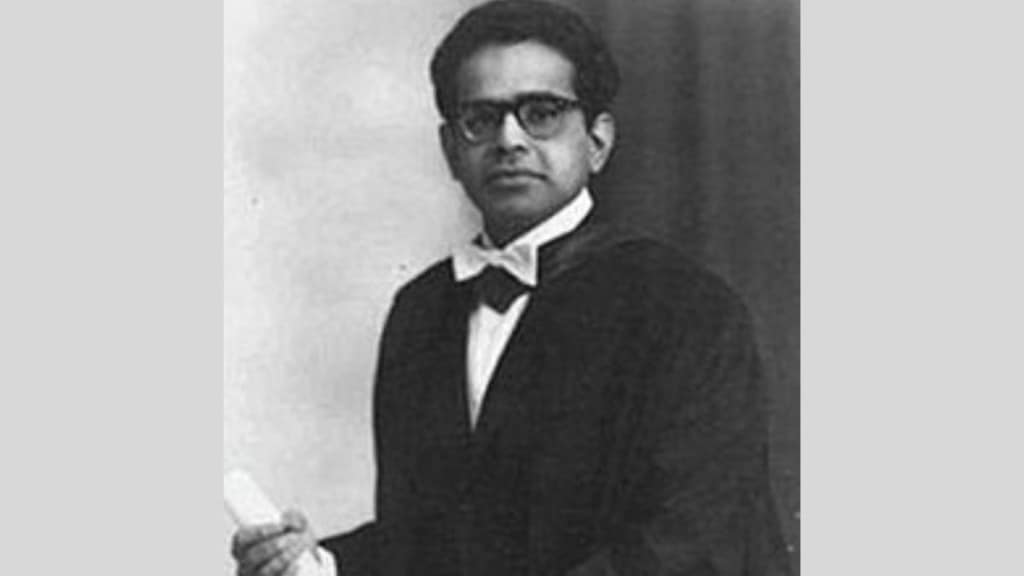

Two great doctors working independently at the same time, 8,000 kilometers apart, achieved this feat. Prof Robert G Edwards, the doctor behind the birth of Louise Brown, became famous for his path-breaking work, and he established the world’s first clinic for IVF therapy at Cambridge, called Bourn Hall Clinic. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2010. In contrast, the brain child behind Durga, Prof Subhash Mukhopadhyay, who achieved the same feat, was denied recognition and faced the hostility of the CPI(M)-led Left Front government in West Bengal, which had rubbished his research. The government ridiculed his work and he was ostracised, which pushed him to end his life. Ironically, the doctor who created the first Indian life outside the womb ended his own life due to banishment and torture by the communist government. His tragic life story inspired the1982 novel Abhi manyu (by Ramapada Chowdhury) and the famous Hindi movie Ek Doctor Ki Maut (1990).

DEVELOPMENT OF NOVEL METHODS FOR INVITROFERTILIZATION (IVF)

Fertilisation is the first process during pregnancy when the egg and sperm fuse at the ampulla of the fallopian tube, forming azygote. The germinal stage of embryonic development begins at the zygote, which undergoes mitotic cell divisions and later transplants as a fetus at the uterus after nine weeks of fertilisation. The fetus undergoes further development for another 31 weeks and then a child is born.

Many paternal and maternal ailments cause the impairment of the natural process of fertilisation. To over- come this, many researchers, including Prof Robert G Edwards and Dr Patrick Steptoe at Cambridge, started working on harvesting eggs and sperm, fertilising them outside the human body, and then transferring the zygote back to the uterus. At the same time, Prof Subhash Mukhopadhyay, who was a Professor of Physiology at Bankura Sammilani Medical College, formed a team with Prof Sunit Mukherjee, a Professor of Food Technology and Biochemical Engineering at Jadavpur University, and Dr Saroj Kranti Bhattacharya, Associate Professor of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Calcutta Medical College ,to develop a method for successful invitro (Latin word meaning ‘inglass’) fertilisation. Prof Mukhopadhyay stimulated the ovary using human menopausal gonad otropin (hMG) (also called Menotro- pin) to increase the success probability. Since Prof Edwards’s team failed to achieve stimulation, it used a retrieved oocyte from a natural menstrual cycle for fertilization.. To overcome the problem of a shortened luteal phase, which was one of the reasons for the failure of stimulation, Prof Mukhopadhyay developed the cryopreservation technique for human embryos. Hecryopre-served the human embryo using DMSO as a cryoprotectant before transferring them, after thawing, in another natural cycle. In contrast to the Cambridge team’s invasive trans-abdominal laparoscopic procedure, Prof Mukhopadhyay employed a new transvaginal colpotomy procedure to fetch the oocytes, which was a minimally invasive and more efficient method.

Ovarian stimulation using hMG hormone, a minimally invasive transvaginal approach for aspirating oocytes, and cryopreservation of embryos, the three major ingredients of IVF developed by Prof Mukhopadhyay, are currently the standard practice used by IVF clinics across the globe.

THE DURGA STORY

Prabhat Kumar Agarwal and his wife Bela Agarwal approached Prof Mukhopadhyay for infertility treatment, primarily due to an ailment in the fallopian tubes. Though cautioned by Prof Mukhopadhyay that the procedure could result in the deformation of the baby, the couple agreed to “try a new method.” He performed ovarian stimulation using hMG and aspirated fluids from follicles. After screening, he co-incubated them with the sperm for 24 hours in flasks for fertilisation. The resulting zygotes developed into embryos which he slowly froze in another flask before cryopreserving them. After 53 days of cryopreservation, he thawed the em bryos and transferred them to the uterus of Bela Agarwal in her later menstrual cycle. He performed all the procedures at his home, maintaining appropriate conditions. She delivered a healthy baby on 3 October, 1978 through a caesarian procedure. The news was made public by Amrita Bazar Patrika on 6 October, 1978. In the report, the newspaper quoted Dr Mani Chhetri, the Director of Health Services (DHS), as finding the claim “quite convincing. If the team could now prove it, West Bengal would get a place of pride in the medical world”. Since she was born on the first day of Shardiya Navratri that year, she was named Durga. Later, the parents changed her name from Durga to Kanupriya before her school admission as they feared their daughter could be treated as abnormal.

Prof Subhash Mukhopadhyay presented his pioneering work at various conferences in India and published the cryopreservation methodology in the Indian Journal of Cryogenics in 1979.

IGNOMINY AND TRAGEDY

The path-breaking work of Prof Subhash Mukhopadhyay, resulting in the birth of the first Indian IVF baby, was derided by the Indian medical fraternity. At a meeting organised by the Indian Medical Association (IMA) and the Bengal Obstetrics and Gynaeco- logical Society(BOGS) at Chittaranjan Cancer Institute, he presented pictures of invitroembryos, but the people ridiculed him.

The DHS, West Bengal, barred him from presenting his work at any conference and refused permission to apply for a passport to attend international conferences to which he was invited. The Left Front government in West Bengal set up a four-member inquiry commit- tee under the chairmanship of Dr Mrinal K Dasgupta, a Radio-Astronomer, in which neither he nor other members had the required expertise to evaluate the work.

The committee not only doubted every aspect of his work but put ridiculous farrago of infuriating cretinous questions to humiliate him. He said to the committee, ‘It is fine, don’t believe me, I will do it again. That is how science works. ’Fearing the same fate, the parents of Durga refused to participate in the inquiry or undergo any medical checkup. The committee, in its four- page report submitted to Nani Bhattacharjee, Health Minister in the Jyoti Basu government, concluded the work to be bogus and unfeasible. Following this, the government transferred him to the Regional Institute of Ophthalmology, and he was not allowed to pursue his work.

He suffered a heart attack due to stress in 1980. Facing ignominy, he committed suicide by hanging on 19 June 1981. In his suicide note, he wrote, “I can’t wait every day for a heart attack to kill me.” A brilliant scientist who could have contributed immensely to the field of reproductive biology with his cutting-edge research and brought laurels to India, he left the world dejected and unrecognised.

LIFTING THE VEIL ON HIS WORK

Although his wife, Namita Mukhopadhyay, and colleague Prof Sunit Mukherjee continued their relentless effort to get him due recognition, he and his work slowly faded into oblivion. Two decades later, Dr TC Anand Kumar, ex-Director ICMR-NIRRH (Indian Council of Medical Research–National Institute for Research in Reproductive and Child Health), credited with the birth of Harsha Vardhan Reddy Buri, India’s first“ scientifically documented” IVF baby on 6 August 1986, lifted the veil on the work of Prof Subhash Mukhopadhyay. Like a true scientist, during his visit to Kolkata in 1997 to attend the Indian Science Congress, Dr Anand Kumar went through the documents of Prof Mukhopadhyay, which convinced him that Prof Subhash Mukhopadhyay was the creator of the first Indian test tube baby. He publicly acknowledged this and wrote an article in different journals. Had he kept silent, the world would have never known the accomplishments of Prof Mukhopadhyay.

In 2002, the ICMR recognised Prof Subhash Mukhopadhyay as the pioneer of IVF in India and later started an award in his memory in 2012. At an event organised in memory of Prof Mukhopadhyay in 2003, Durga also came forward and narrated the story behind her birth. In 2007, Prof Mukhopadhyay was included in the Dictionary of Medical Biography, UK. After Ronald Ross and U N Brahmachary, he became the third scientist from Kolkata to be included in the list. The Department of Reproductive Physiology at Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College, Kolkata, was later renamed after him. Dr Sub- hash Mukherjee Memorial Reproductive Biology Research Centre at Behala, Calcutta, was established in1985 by the Jadavpur University, Indian Cryogenics Council, and Behala Balan and a Brahmachari Hospital. In 2018, his life sized statue was unveiled at his birthplace, Hazaribagh.

OTHER NOTABLE CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr Mukhopadhyay was the first to observe a correlation between emotional stress and PCOD that causes infertility. He discovered that the hCG hormone is important for maintaining the corpus luteum immediately after fertilisation and is required for healthy menstrual cycles. He also contributed significantly to understanding Testicular Feminisation Syndrome and advocated using Fish Protein Concentrate (FPC) as a nutritional supplement.

BIOGRAPHY

Prof Subhash Mukhopadhyay was born to Dr Satyendra Nath Mukherjee, a famous radiologist, and Jyotsna Devi at Hazaribagh, Bihar (now Jharkhand) on January 16, 1931. He was a descendant of Krittibas Ojha, who had composed Krittivasi Ramayan in Bengali. After schooling at Calcutta, he graduated with honors in Physiology from the city’s Presidency College. He received his MBBS degree at the National Medical College, University of Calcutta, in 1954. He was awarded the Hemangini Scholarship and College Medal for securing the first rank in.

OBSTETRICS And GYNECOLOGY

In pursuit of his keen research interest, he worked on “The biochemical changes in normal and abnormal pregnancy” for his first PhD in Physiology under the guidance of Dr Sachchidananda Banerjee at the Presidency College, Calcutta. In 1961, he received the Colombo Scholarship to work at the Clinical Endocrinology Research Unit in Edinburgh, UK. Under the tutelage of Prof John A Loraine, he worked on “Developing new, sensitive bioassays for luteinizing hormone based on depletion of cholesterol in rat ovaries,” leading to his second PhD degree. He returned to India in 1967 and joined Sir Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College, Calcutta, as a lecturer, where he later became a professor. Staying at the college campus, he built an animal house for research purposes that housed animals ranging from mice to primates. The government transferred him as a professor of Physiology at Bankura Sammilani Medical College, where he later became head of the department and worked on IVF leading to the birth of Durga. He married Namita in 1960, and they did not have children by choice as he wanted to complete his research.

The writer is Group Leader, Transcription Regulation Group, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), New Delhi .He blogs at http://www.neelsb.com.