Several state-run and private companies with principal or incidental interest in mining are being forced to cough up huge sums, potentially aggregating soon to Rs 1 lakh crore, as mineral-rich Odisha and Jharkhand have slapped recovery notices on them for “illegal mining”. In some cases the amount being demanded is big enough to wipe out the entire cash reserves of the firm concerned and substantially erode its net worth, besides crippling its mining activities.

These state governments are now armed with a broader definition of “illegal mining” thanks to an August 2017 Supreme Court judgment which, among other things, said: “Illegal mining takes within its fold excess extraction of a mineral over the permissible limit even within the mining lease area which is held under lawful authority, if that excess extraction is contrary to the mining scheme/plan/lease or a statutory requirement.”

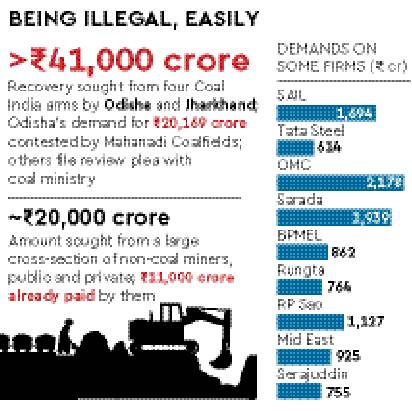

Curiously, even though the court hasn’t expressly said the judgment would extend to coal mining — the order was issued on a PIL filed in the context of the MP Shah Commission of Inquiry on illegal mining of iron ore and manganese —, state-run Coal India’s arms too have received show-cause notices by the two states, asking why they are not (collectively) liable to pay fines of over `41,000 crore, under the Section 21 (5) of the Mines & Mineral Development Regulations (MMDR) Act, 1957. Mahanadi Coalfields has been asked by Odisha to pay `20,169 crore, while Jharkhand authorities are learnt have demanded several thousands of crores from Coal India’s three other subsidiaries — ECL, BCCL and CCL.

For perspective, India’s cash reserves are now around Rs 38,000 crore; the company reported a net profit of Rs 9,266 crore in FY17; and profits of Rs 2,352 crore, Rs 369 crore and Rs 3,005 crore in Q1, Q2 and Q3 in FY18, respectively.

To make the order applicable to coal mining, states are relying on an affidavit by the ministry of mines to the court, which the latter cited in the judgment.

The ministry had said in the affidavit the relevant piece of law — Section 21 (5) of the MMDR Act — “would apply to all minerals raised without any lawful authority..” and that penalties would arise “in respect of any form of mining activity.”

However, a source from the ministry of mines has told FE that the states are making an expansive interpretation of the SC judgement to fine CIL.

A coal ministry official said, “The showcase notice has been replied to by Mahanadi Coalfields, saying that the SC order doesn’t apply to Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act. The Coal India arm has also argued that the SC verdict was only in relation to iron ore and manganese. However, the coal ministry official added that the “calculations (by the Odisha government) in the penalty notice” were wrong; he didn’t explain how calculations were relevant if the premise of the notice itself was being challenged.

As for ECL, BCCL and CCL which are faced with demand notices from Jharkhand government, they have filed a review petition with the coal ministry (for its approval), the sources said, in which the firms have sought a review of the MMDR Act and pointed out “infirmities of the state’s notices.”

But as things stand, there seems to be little resistance to the states’ move by at least the miners of iron and manganese ores. Between them, these companies have already paid over Rs 11,000 crore to the two state governments, while the demands so far on them have been in excess of Rs 20,000 crore. A large cross section of the Indian non-coal mining industry is impacted by the move: state-run SAIL, Orissa Mining Corporation and BPMEL have been slapped the fines for environmental/forest law violations while the private firms hit hard include Tata Steel, Sarda, RP Sao, Mid East among others (see table).

According to Section 21 (5) of the MMDR Act, “whenever any person raises, without any lawful authority, any mineral from any land, the state government may recover from such person the mineral so raised, or .. the price thereof..” The court has reinforced this section by stating that the words “any land” are not confined to the mining lease area (meaning not just violation outside the lease area but those within the lease area also attract penalty); also, it added that as far as the lease area is concerned, extraction of a mineral over and above what is permissible under the mining plan or under the Environmental Clearance amounted to “extraction without lawful authority.” The question that still existed, according to analysts, is whether MMDR Act coverd coal.

Meanwhile, iron ore miners have said that Section 8A of the MMDR Act, under which many mining leases have been terminated, has also hit them hard. “It is expected that the statute will impact around 50 million tonne of iron ore production capacity in Odisha alone. Going by the experience of (captive) coal block auctions, restart of mining leases terminated vide this provision may (take) anywhere between 1-2 years. This can cause disruption in iron ore supply in medium to long term.

The national income data released last week showed that the mining/quarrying sector gross value added contracted by 0.1% y—o-y, in Q3FY18.