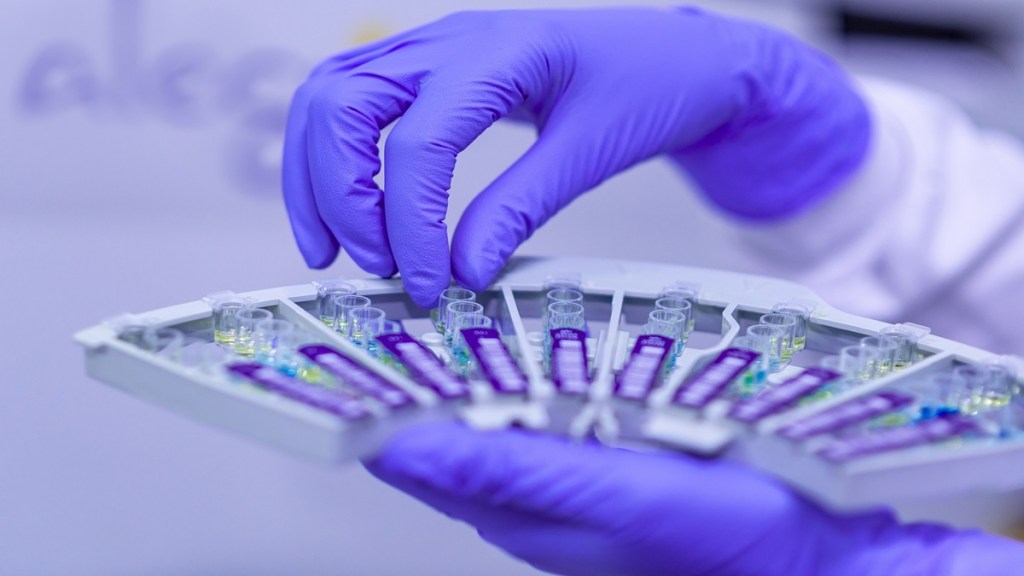

A team of scientists at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln will soon have a long-lasting swine flu vaccine that’s safe and effective. The team is currently conducting a long-term live hog experiment.

In 2009 during the swine flu pandemic and the emergence of the H1N1 strain, the virus originated in pigs before infecting close to a fourth of the entire world during the first year.

According to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the disease outbreak had to led to almost 12,500 U.S. deaths and nearly 575,000 around the world.

“Considering the significant role swine play in the evolution and transmission of potential pandemic strains of influenza and the substantial economic impact of swine flu viruses, it is imperative that efforts be made toward the development of more effective vaccination strategies in vulnerable pig populations,” says Erika Petro-Turnquist, a doctoral student and lead author of the study, in a university release.

Eric Weaver, associate professor and director of the Nebraska Center for Virology, and his team have been using Epigraph, a data-based computer technique co-developed by Bette Korber and James Theiler of Los Alamos National Laboratory. According to media reports, the researchers wanted to use the technology to develop a broad-based vaccine because of how difficult influenza can be to prevent, thanks to rapid mutations.

It is noteworthy that the Epigraph algorithm makes it possible for scientists to analyze numerous amino acid sequences among hundreds of different viral variants in order to create a vaccine “cocktail” of the three most common epitopes, which are parts of viral proteins that cause the immune system to react.

According to the National Institutes of Health, this could soon lead to a universal flu vaccine, which is one that is at least 75 percent effective and protects against multiple types of flu viruses for at least a year in all age groups.

Moreover, in order to make the vaccine more effective, the vaccine is delivered via adenovirus, which is a common virus that causes cold-like symptoms. Reportedly, it’s used to trigger another immune reaction by mimicking a natural infection.

The findings of the study is published in the Frontiers in Immunology journal.

According to a press statement, Weaver’s team continues to pursue the research, with next steps including larger studies and possibly a commercial partnership to bring the vaccine to market.