During the past 20 years, the inflation-adjusted average hourly wage of non-management US workers, also known as production and nonsupervisory employees, has risen 13%. That’s not exactly a rip-roaring pace — 0.6% a year. Then again, real hourly wages for production and nonsupervisory employees fell in the 1970s and 1980s and rose at only a 0.3% annual pace in the 1990s.

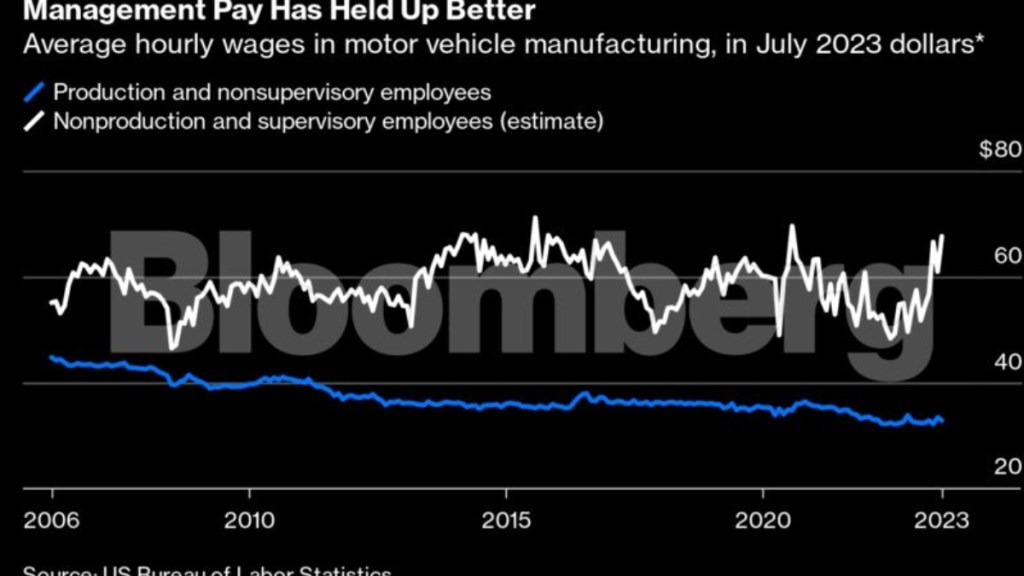

One group of American workers has had a much different experience over the past two decades. The average hourly wage for autoworkers on the production line has dropped 30% since 2003.

Autoworkers still make more per hour than their peers in the rest of the private sector. They also work more hours per week (44.3 in July compared with 33.7 for private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees overall) and receive better benefits. But the real-wage decline since 2003 explains a lot about why the United Auto Workers union has approached this year’s contract negotiations with the Detroit Three automakers — General Motors., Ford Motor and Chrysler owner Stellantis NV — so aggressively.

These wage data are for all auto manufacturing in the US, including the nonunion operations of foreign automakers and of Tesla Inc., which together now account for just more than half of US auto production, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Most (although not all) of these automakers pay less than the Detroit Three, so that’s one explanation for the decline in real autoworker wages.

Frustration with declining real wages helped drive insurgent Shawn Fain to victory in the UAW presidential election earlier this year, and now Fain is pushing for a 46% pay increase through 2027. If that applied to all production and nonsupervisory workers in the sector, and inflation ran at 2% a year for the next four years, it would bring real hourly wages back to about 5% less than they were in mid-2003. In that sense, it’s not an unreasonable ask.

In another sense, it might be. The UAW made big concessions in the 2000s because US automakers were losing money, with GM and Chrysler eventually going bankrupt. GM, Ford and Stellantis are all profitable now, with a combined net income of $42 billion for the 12 months ended in June and the amount coming from their US operations probably adding up to somewhat less than $30 billion.

But Bloomberg News reported last month that Ford and GM’s internal estimates of the costs of the UAW’s demands — which include a return of cost-of-living increases, a reduced workweek and increased retiree benefits along with the wage increases — peg them at $80 billion per company over the next four years, which would wipe out all those profits and then some.

Automaking is also a lot less economically significant than it used to be. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis measures industries’ contribution to gross domestic product as value added, and the auto industry’s has been shrinking as a share of GDP for decades.

The contrast with United Parcel Service Inc., which acceded in July to most of the demands of the Teamsters union, including an end to two-tier wages, is instructive. UPS has not had a money-losing year since going public in 1999, and rival FedEx last saw red ink in 1992.

The BEA doesn’t publish value-added estimates for the package-delivery industry dominated by the two companies and the US Postal Service, but estimates for broader transportation categories and evidence from the rise of online retail sales indicate that its contribution to GDP has been growing. UPS workers’ wages are growing along with it.