By Raju Mansukhani

Towards the end of August 1965, it was obvious that Operation Gibraltar had failed in its objective, handing India a golden opportunity to cross the cease-fire line. Operation Gibraltar was a disaster not only for the Pakistani Army but also for those who had conceived and unleashed it, namely Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, General Musa the Commander in Chief, President Ayub Khan, and Major General Akhtar Malik.

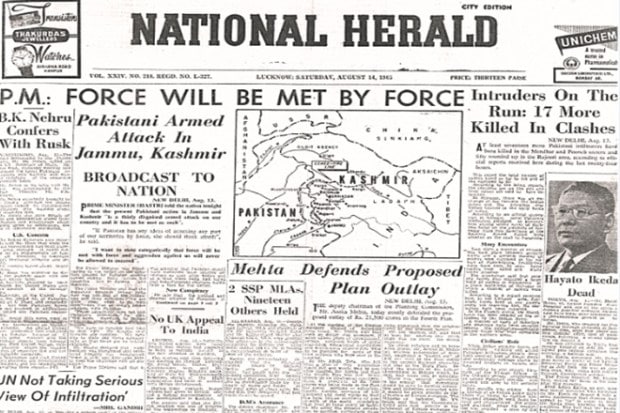

‘Intruders on the run: 17 more killed in clashes’, reported National Herald on its front page on 14 August 1965, “at least 17 more Pakistani infiltrators have been killed in the Mendhar and Poonch sectors and fifty round up in the Rajouri area of Jammu & Kashmir, according to official reports.”

By the middle of August, the total number of raiders killed so far was 126 and 83 others had been captured. The media was also reporting that the intruders were on the run and their rations are said to have been exhausted. In Srinagar, some Pakistani infiltrators were indulging in intermittent sniping under the cover of darkness at the Kashmir Armed Police Lines on the road to Baramulla.

What was inspiring were the stories of exemplary courage shown by unarmed civilians in overpowering the infiltrators. According to a National Herald report, “Dinanath of the Kharab village in Chhamb sector overpowered an armed Pakistan guerilla and handed him over to security forces. The guerilla was sniping from a hilltop at an Indian police party. Unarmed Dinanath went from behind and overpowered the sniper, snatching away his weapon. He was awarded a prize by the authorities. In Budhwla village, Nandlal and two others helped the security forces in capturing two armed guerillas in the same sector…a group of unarmed villagers led by Abdul Aziz apprehended a guerilla by strangling.“

The Information and Broadcasting Minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi, expressed her regret that the United Nations Secretary General U Thant who had got ‘very excited’ over the Kargil incidents in May last is ‘not taking a serious view’ of the infiltrations by Pakistan armed personnel in civilian clothes. At a press conference in New Delhi, after a 5-day visit to Srinagar, she highlighted, “the massive infiltration that the Pakistani armed personnel had effected into Indian territory now…But the Secretary General is not excited. Nobody had taken this infiltration as seriously as it should have been taken.”

On the diplomatic front, India kept up the pressure on Pakistan. In Washington, the Indian Ambassador to the US, BK Nehru, called on the US Secretary of State, Dean Rusk and discussed the latest Pakistani infiltration into Kashmir and massive violations of the cease-fire agreement. The Ambassador also gave details of arms and ammunition seized from infiltrators and information about training given to infiltrators, the type of infiltration attempted, according to a PTI report. Mr Nehru was accompanied by the senior Indian diplomat, PK Banerjee.

Meanwhile at the United Nations, Amjad Ali of Pakistan called on UN Secretary General U Thant and reportedly told him Pakistani forces were not involved in infiltrations and denied any Pakistani responsibility. Amjad Ali’s views were in response to U Thant’s call to him and his government for restraint.

To delve deeper into different chapters of the 1965 war history, ‘The Monsoon War – Young Officers Reminisce 1965 India-Pakistan war’ by Amarinder Singh and Lt Gen Tajindar Shergill, PVSM, provides invaluable details, documents, identifying key decision makers on every front of the war. The authors, in the section titled ‘The Kashmir Theatre: XV Corps’ unfold Operation Gibraltar and the ‘Gibraltar Force’ which was unleashed by Pakistan.

Sometime in early 1965, Pakistan raised the ‘Gibraltar Force’ for infiltration into Jammu and Kashmir. The force was commanded and trained by Major General Akhtar Hussain Malik, General Officer Commanding, 12 Infantry Division of Pakistan at its divisional headquarters at Murree. The infiltrators were 30,000 strong, organised into eight forces with six units each; a unit had five companies with 110 personnel in each. These units were led by junior commissioned officers who had been trained in guerrilla warfare.

The main object of this force was to create conditions in Jammu and Kashmir that would cause the people of that region to rise in rebellion against India in favour of Pakistan. And in so doing, seize the law and order machinery, disrupt administrations throughout the area, including the tenuous route to Ladakh, inflict casualties on the Indian Army and destroy its logistics capabilities.

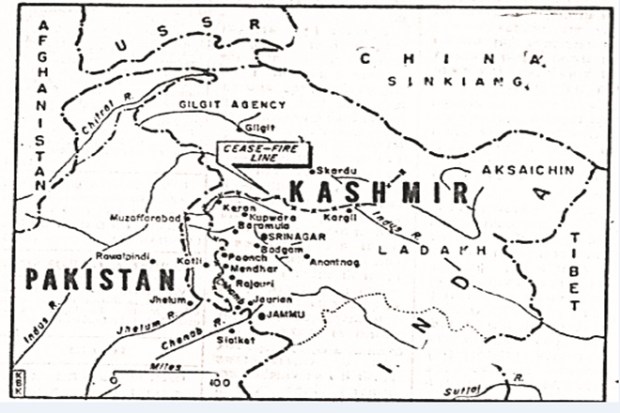

The 12 Infantry Division had been responsible for holding the cease-fire line which had a frontage of over 640 kilometres, along the border of Pakistan and India. The Gibraltar Force comprised six groups, codenamed: Tariq, Qasim, Khalid, Salahuddin, Ghaznavi and Babur. Of course,also included in the Force were the mujahids, civil armed forces and police forces who had been handpicked for the operation.

“Operation Gibraltar was the brainchild of the Pakistan Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who thought the Kashmiri people were ripe for rebellion; added to it was the unlikelihood of the Indian Army crossing the cease-fire line or the international boundary in retaliation,” it is revealed in The Monsoon War, a statement of fact.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s career, and ability to drum up support for Pakistan on the international arena, had been going strong during these years. Moreover, the Pakistan establishment was joyously aware of the low morale of the Indian Army, after defeats in the Sino-Indian conflict in 1962.

These were the years when Pakistan was assured by the Chinese that should India cross the cease-fire line, China would respond suitably by applying military and political pressure. 1965, in many ways, can be seen as a landmark year in Sino-Pak relations, cementing their ties which have continued till date. It was to Bhutto’s credit that he managed to persuade Field Marshal Ayub Khan to agree to the operation.

Military historians have often commented that it is rare a foreign minister should dictate the nation’s offensive military policy, but Bhutto did so and by May 15, 1965, he got the approval from President Ayub Khan.

As Amarinder Singh and Lt Gen Tajindar Shergill PVSM explained, the military aims of the Operation were in sync with the objectives: 1. To disrupt the Indian military and civilian control of the state; 2. To encourage, assist and direct an armed revolt by the people of Kashmir against military occupation; 3. To create conditions for an advance by the Azad Kashmir forces into the heart of occupied Kashmir and the eventual liberation of the India Held Kashmir (IHK).

The Pakistan military envisaged a two phase approach: In phase one: create a shock wave by launching raiding or infiltrating attacks on select targets and prepare the ground for a general uprising. In phase two: incorporating the civil uprising into the guerilla operations. President Ayub Khan gave his formal consent. The operation was launched on 5 August 1965. The political intention was to make India and the United Nations believe that the planned uprising was that of the Kashmiri people alone.

In the event, however, the Kashmiri people did not rise; they actively assisted the Indian Army to get rid of this unprovoked aggression on Jammu and Kashmir. The Indian Army acted swiftly to sever routes of the infiltrators west of the cease-fire line by capturing terrain across the line in Kargil that threatened into Ladakh on 27 August 1965; setting up improved defensive posture in Tithwal; and capturing Haji Pir Pass that linked Uri to Punch thus, further posing a threat to Pakistan communications from Muzaffarabad to Kotli, opposite Punch, Naoshehra and Jhangar.

Towards the end of August 1965, it was obvious to Major General Akhtar Malik that Operation Gibraltar had failed in its objective, handing India a golden opportunity to cross the cease-fire line. Operation Gibraltar was a disaster not only for the Pakistani Army but also for those who had conceived and unleashed it, namely Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, General Musa the Commander in Chief, President Ayub Khan, and Major General Akhtar Malik.

There was a negative impact of the defeat: the international community and within Pakistan there were political repercussions, particularly since the operation had been launched in secrecy; and of course, the opportunity for India to cross the cease-fire line moving to Muzaffarabad after the capture of the Haji Pir Pass. More so there were the 30,000 or so personnel of the Gibraltar Force in disorganized groups in Kashmir who were being hunted by the Indian Army and the local voluntary militias.

In War Despatches Indo-Pak Conflict1965 of Lt Gen Harbakhsh Singh VrC, the Indian Army’s state of preparedness, its intelligence and alertness about happenings in Pakistan are spelt out with fascinating details and a sense of candour and forthrightness.

“Acts of sabotage and a subversion, a familiar feature of Pak intrigues in the Valley, touched a new high during July 1965 and reached its peak in the first week of August. Specially trained agents and saboteurs were projected into J&K for mass scale subversive activities, in order to generate amongst the populace an atmosphere of despair and despondency with a view to eroding the authority of the civil administration. The resulting situation of lawlessness and disorder, it was hoped, would push the government to the brink of an abyss, ready to topple over with the next stage of large-scale infiltration,” the General stated.

The Indian Army and civil administration were facing up to acts of arson in the towns of Poonch and Srinagar on 30th June and 8th July respectively. Large number of houses and shops were razed to the ground. Time bombs were detected in public buses. A few were planted with the obvious intent of assassinating political leaders. Needless to say, there was an opportunistic segment in J&K that rallied with the Pak forces and the word ‘Jehad’ was probably heard openly on the streets of Srinagar from public platforms.

Said Lt Gen Harbakhsh Singh, “I continued to be apprehensive of the situation in J&K; we had for years deployed our regular forces in penny packets all along the cease-fire line and hence little or no reserves to counter Pak’s aggressive designs, leave alone the ability to retaliate – a state of affairs that no commander can be happy about. To remedy the situation, I approached Army HQ repeatedly for a revision in the existing policy and arrangements for the security of the ceasefire line.”

“On 1 August 1965, a meeting was held in Srinagar with the Chief of the Army Staff, General Officer Commanding XV Corps and myself to prepare to project our views before a joint civil and military conference. Our unanimous opinion: the Army was over-extended along the ceasefire line and the police battalions positioned along the border were of an indifferent standard.The Army should, I pointed out, hold tactically sound dispositions, covering the main approaches, behind a screen to be provided by an irregular force like the J and K militia. The proposal was accepted in principle by the Chief of Army Staff.” The General was now in far greater control, ready to foil the diabolical plans prepared by Pakistan.

“The plan of infiltration was brilliant in conception,” wrote Lt Gen Harbakhsh Singh in War Despatches, “the raiders were to infiltrate in small groups between 1st and 5th August 1965, concentrate at select points and then converge into the Valley from different directions. Simultaneously, a few columns were to penetrate deep into 25 Infantry Division Sector for lodgement in certain areas.” The festival of Pir Dastagir Sahib on 8 August, and the anniversary of Sheikh Abdullah’s arrest on 9 August were the two days when the raiders had planned to sneak into the processions, fully armed and ready to create chaos and mayhem while staging the armed revolt.

Lt Gen Harbakhsh Singh admitted that the news of Pakistan’s elaborate plan “came to us as a surprise. Our intelligence had given only vague inklings of what was happening on ‘the other side of the hill’; of the actual scale and scope of the massive campaign that was to follow, we had no information.”

War Despatches provides the gritty details of the infiltration campaign and the swift responses of the Indian Army: with the raiders holed up in areas around Rajouri and Chhamb sector; when the columns of infiltrators were on their way to Srinagar;the attacks and counter-attacks on Haji Pir and Kishanganga Bulges; and the formation of a separate headquarters to deal with counter-infiltration called Headquarters SRI Force. Kalakot, Dharamsal, Naghun, Gali Picquet, Doda and Punch, Jaurian camp: these were just some of the dots on the map which got joined together in this India-Pakistan conflict.

The failure of the infiltrator campaign exploded the myth created by Pakistan, at home and abroad, that the majority of Kashmiris were impatiently waiting to be ‘liberated’. In fact, said Lt Gen Harbakhsh Singh VrC, the success of the anti-infiltration campaign is attributable in a large measure to the reluctance of the locals to cooperate with the infiltrators.

Author is a researcher-writer on history and heritage issues; former deputy curator of PradhanmantriSangharalaya.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.