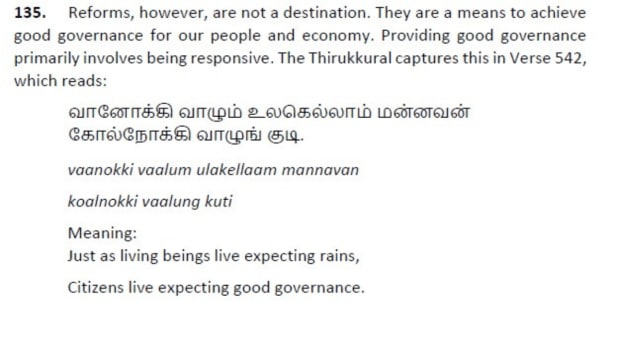

Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s budget speeches have long carried a distinctive feature—quotes from poets, philosophers, and classical literature. Budget 2025 was no exception. While presenting her direct tax proposals, Sitharaman invoked the Tamil language text on commoner’s morality consisting of 1,330 short couplets, Thirukkural, quoting verse 542 to emphasise the expectation of good governance from rulers. The choice of Thiruvalluvar’s words—”Just as living beings live expecting rains, citizens live expecting good governance”—seemed aimed at reinforcing the government’s commitment to responsive administration and tax reforms.

But this carefully placed literary reference makes us question if it is a philosophical foundation for governance or a well-timed rhetorical device to mask the economic shortcomings. The invocation of Thirukkural, an ancient Tamil text revered for its ethical and moral teachings, subtly shifts the focus from policy specifics to cultural ethos. Popular Tamil scholar Solomon Pappiah’s interpretation of the same verse—”People live anticipating a ruler’s honesty”—could just as easily be read as a critique rather than an endorsement, given the government’s ongoing struggles with tax simplification and compliance burdens.

She has done it before!

Sitharaman has a history of embellishing her budget speeches with literary allusions, often drawing from regional languages to establish cultural resonance. In 2019, she cited Chanakya Niti, Urdu poet Manzoor Hashmi, and Swami Vivekananda. In 2020, after the abrogation of Article 370, she turned to Kashmiri poet Pandit Dina Nath Kaul. The pandemic-era budget of 2021 featured Rabindranath Tagore, and 2022 saw her leaning on the Mahabharata to justify taxation policies. This year, she began her speech with a quote from Telugu poet Gurajada Apparao: “Desamante matti kaadoyi, desamante manushuloyi” (A country is not just its soil, but its people). While the sentiment behind this line is commendable, it was presented alongside economic measures that may take time to significantly alleviate the immediate challenges faced by the middle class—a group that remains central to her tax reforms.

There’s a pattern here: the strategic use of poetry to soften the harder edges of fiscal policy. While these references lend a certain gravitas to the speech, they also risk becoming a convenient distraction. The invocation of literary giants can’t replace substantive economic action, and if history is any indicator, the public’s expectations—like Thiruvalluvar’s citizens awaiting good governance—are often left unmet.