If the procurement-based system is replaced by a nationwide price deficiency support scheme for agriculture produce, the MSP system could not only become more efficacious but also considerably less expensive, Niti Aayog member Ramesh Chand said on Friday.

Stating that procurement incidentals like storage, handling, assorted mandi levies and transportation inflate the cost of MSP operations by some 50%, he said that direct cash payment to bridge the gap between the market prices and MSPs would save these costs. In kharif 2018 for instance, he said, quoting his own research, the entire MSP operations for all crops could have cost about Rs 55,000 crore, if a scheme similar to Madhya Pradesh’s Bhavantar were to run throughout the country sans any procurement.

In other words, a pan-India Bhavantar-like scheme could have helped the government save around Rs 23,000 crore per annum in procurement cost. The Centre’s annual expenditure on procurement of all agricultural crops under MSP schemes was estimated at about Rs 1.33 lakh crore for 2017-18. A major chunk of it (about Rs 1.19 lakh crore) is paid to the Food Corporation of India (FCI) on account of procurement of rice and wheat. Agri cooperative Nafed spent Rs 13,596 crore in 2017-18 on procuring pulses and oilseeds on behalf of the government.

Refuting the notion that assured price deficiency payments to farmers could encourage traders to collude and hammer down the prices, Chand said such fears were unfounded. Although the prices of soyabean in Madhya Pradesh crashed in last kharif season, that could not be attributed to Bhavantar scheme, he asserted, adding that during the season the crop’s prices fell in Maharshtra and Rajasthan as well.

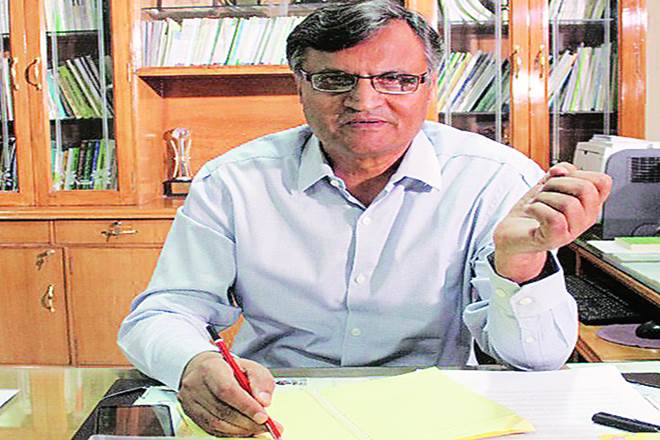

Speaking at The Indian Express Group’s Idea Exchange programme, Chand said a knee-jerk replacement of subsidies on fertilisers with cash transfer could result in an ‘output shock’, with a 10% decline in production of foodgrains. Pointing out that the power subsidies on farming itself amounts to some Rs 1 lakh crore annually, he said removal of this sop could lead to 40% decline in farmers’ use of irrigation water, without any significant drop in yields.

On the target of doubling farmers’ income by 2022, he said this could be achieved only by imparting more competition in the agriculture market by dismantling the grip of APMC mandis and stepping up corporate investments in agriculture via contract farming, among others. Of the total investments in agriculture, over 84% are by farmers themselves while 13% come from the public sector and a meagre 2.4% are by corporates.

Speaking about the states’ reluctance to undertake reforms in agriculture markets, he said, while APMCs ought not to be abolished, farmers must be given the option to sell to other players.

While the target to double farmers income was set in 2015-16, the idea was to increase their income by an average of 10% annually. In the last three years, however, the annual growth was around 6% only, which raised the ask rate now to 12%.

Despite deficient monsoons, average gross value added (GVA) growth in agriculture has been 2.9% in the past five years. The farm GVA growth is estimated to be 2.8% in the current financial year, Chand said. In the “agriculture and allied activities” category, livestock segment has been growing at a healthy rate of 6% per annum much higher than grains, a sign that “the more the intervention by the government, the less the growth rate,” he said.