The century from 1815 to 1914 was a relatively peaceful one in Europe. Regions coalesced into nation states; trade grew substantially as the factory system made possible specialisation and large-scale production; associations linked professionals across countries; and international agreements promised negotiated settlements to disputes. When armed conflicts happened, they tended to be limited and not to last more than a few weeks. The so-called Victorian Era saw cousins on the thrones of major European powers – from Russia in the east to Germany in the centre to Great Britain in the west.

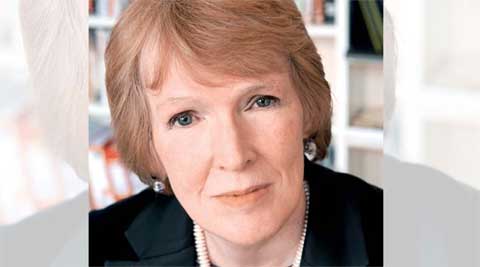

And then – quite disastrously – the ‘concert of Europe’, as it was called, broke down in discord in the first half of the twentieth century. Historians are still trying to understand how and why it happened. One of the most illustrious of them, Canadian Margaret MacMillan was in New Delhi recently at the invitation of the European Union to share her insights into the causes of the war and its consequences. In a magisterial sweep of one of the most troublesome periods of European history she showed how individual predilections, competitive strains, old grudges, and over-weaning ambitions came together to ensure that an assassination in Sarajevo would engulf the entire continent. Prof MacMillan’s lecture – graciously hosted by the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, the largest archive of the personal papers of the statesmen of modern India – is now available on the NMML website. Her interview with the EU Delegation is similarly available on the EU Delegation’s facebook page and website.

Of course, the lessons of the war would, of course, not be learnt by enough people, and with sufficient clarity to avoid a second conflagration in 1939; but the link to subsequent peace initiatives on the European continent is undoubted. Speaking at the Nehru Memorial event to an audience of parliamentarians, diplomats, academics, military officers, the Press and students, EU Ambassador João Cravinho – a former scholar at St Antony’s College, Oxford, of which Prof MacMillan is currently the Warden – remarked that ‘it was only really after the Second World War that we had powerful political leaders deeply believing that it was possible to alter the way in which European politics played itself out, in a manner that would render impossible the kind of path to war that had become Europe’s greatest export product to the world twice during the first half of the twentieth century’. He observed that ‘the single most important message behind the creation of the European Union is not the common market, which was the very simplistic and reductionist way in which it was understood by some quarters during last century, but rather the European Union as a peace project, a very political project aimed at bringing peace to a continent that spread war to all corners of the world during the first half of last century. It was this peace project that was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012’.

For Updates Check Economy News; follow us on Facebook and Twitter