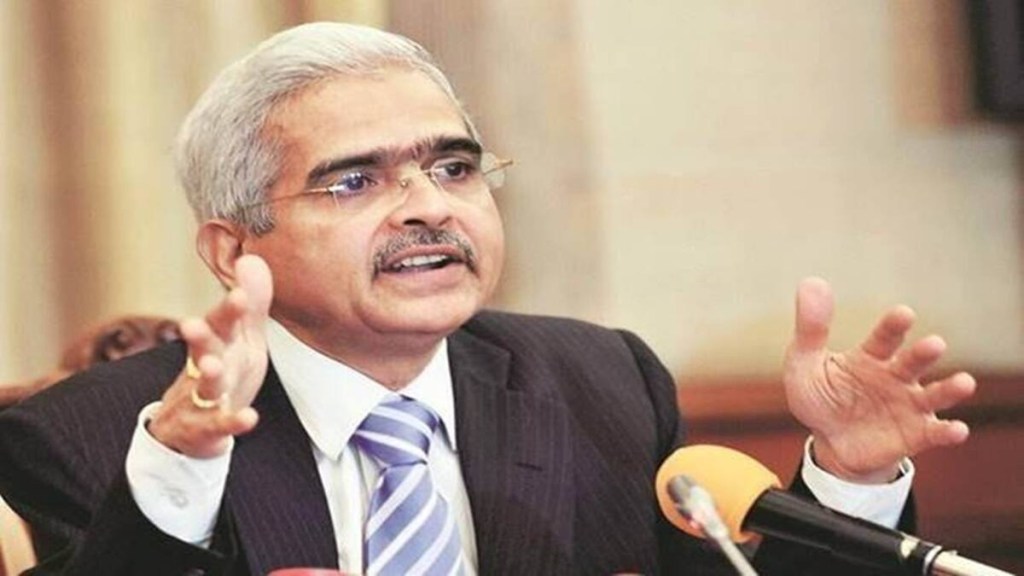

The relationship between the central bank and government in any country is one of interdependence. Therefore, there needs to be a constant dialogue between the two institutions, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Governor told financial magazine Central Banking in an interview.

Das was answering a question on the RBI having turbulent relationship at times with Centre in the past, and whether it is possible to maintain central bank’s independence and avoid fiscal dominance.

“The relationship between the central bank and government, in any scenario, in any country is one of interdependence. Therefore, the relationship has to be based on a constant dialogue. To bring about improvements in the financial sector, we need legislative changes,” Das said.

The strained relationship between RBI and Centre peaked during the end of tenure of former RBI Governor Urjit Patel, who resigned about nine-months ahead of his three-year term in 2018 citing personal reasons. Patel, who was the twenty-fourth RBI Governor, reportedly had the shortest tenure that any governor had since 1992. His move was later followed by former deputy governor Viral Acharya in 2019, who quit from his role citing personal reasons about six months ahead of his term end.

Speaking about the current dynamics of communication with the Centre, Das said the RBI did not have certain powers to bring about necessary legal changes in the non-banking finance companies (NBFC) sector, which acted as an impediment in regulator’s capacity to supervise the sector and thus it engaged with the Centre and brought in necessary amendments in the law. Further, necessary legal changes were also brought in the co-operative banking sector in consultation with the Centre, he said.

Similarly, the government also needs the central bank’s support in many situations, Das said. “A dialogue does not mean a compromise of autonomy at all. In the end, you decide what you want to do. But it is useful to share each other’s concerns,” Das said.

When asked about his key priorities after becoming the RBI Governor in 2019, Das said the regulator was primarily tasked with two main challenges—GDP growth showing moderation signs and severe liquidity squeeze in the aftermath of collapse of conglomerate Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services.

“There was no liquidity flow. But more than that, a lack of confidence was slowly building up in the system. There were worries being expressed all around that other non-bank lenders might fail. There was a crisis of confidence in the financial markets,” Das said. In response, as inflation was well below 4% target, the RBI started with repo rate cuts to spur growth. Further, the RBI gradually infused liquidity in system to enhance market sentiment.

However, the liquidity injection had to be done in a very smooth manner, Das says, without showing any sign of panic or ringing any alarm bells. “Central bank action should not be seen as panicky,” he said, adding that the RBI injected liquidity by buy/sell swap of foreign currency and bought about $10 billion in two instalments. The buy and sell auction was for a period of three years, the governor said, which meant that the RBI gives back the dollars in three years and takes back rupees, thereby injecting liquidity for a finite period.

Lastly, Das reiterated his stance on cryptocurrencies, saying it is purely a “speculative” activity and for emerging economies like India, cryptocurrencies have a serious consequences on country’s monetary system and regulation of capital flows. “Ultimately, it will cause financial stability challenges for emerging market economies,” Das said.