With the sharp fall in the premiums over the last six months (and the likelihood that they will stay low/fall further given the US Federal Reserve’s troubles with managing inflation), Indian exporters are a confused lot. Historically, even though most people expected the rupee to keep falling, a premium of 4-5% per annum (pa) provided some comfort to companies who wanted to hedge some part (or all) of their exposures forward to reduce the risk of staying fully exposed.

However, today, with the premiums at around 2.1% pa (about 1.70 paise for 12 months), it would appear almost foolish to hedge to 12 months when the rupee has fallen by more than that over 12 months nearly 60% of the time since 2011; in fact, it has fallen as much in just two months nearly 20% of the time. This suggests that not hedging (or hedging very modestly) could be a viable strategy.

Of course, this would mean that you are carrying a large amount of risk. Since 2011, the maximum appreciation of the rupee over a 12-month horizon has been nearly 8 rupees, and it has appreciated in absolute terms (again, over a 12-month horizon) more than 24% of the time.

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t – staying fully unhedged is not a responsible option and hedging at these premiums is not attractive.

Enter the Mecklai cavalry.

Close followers of our approach would know that we develop structural solutions to address just such difficult situations, and have recently developed a momentum-based toggle where you would switch between two hedge strategies given the USDINR momentum at the start of the period. To further tighten the process in the current situation, we have overlaid a volatility trigger, which selects either the toggle rate or a zero hedge depending on the volatility level—note that we use zero hedge as one of our strategies since, as explained earlier, it is clearly a winning approach a large part of the time in a low premium environment.

Also read: Digital security and India

Another issue to be wary of is the reality that the market can change its nature again at any time, and, while RBI is on the job controlling volatility, global uncertainty is always threatening to break things open again. Thus, being locked into a 12-month hedge program may not be the best idea in this kind—and, some would argue, in any kind— of market environment.

To address this, we have further tuned the approach to identify risk out to 12 months (the business plan period) but follow the toggle/volatility strategy 6 months at a time. Thus, we would treat each exposure as if it were a 6-month exposure, settle it against spot at the end of 6 months, and, assuming no major change in the market environment, rerun the programme for the second 6 months. This way, if things suddenly change— either in terms of another sharp decline in the rupee or a (however unlikely) rise in the premiums, you can pull out and reassess.

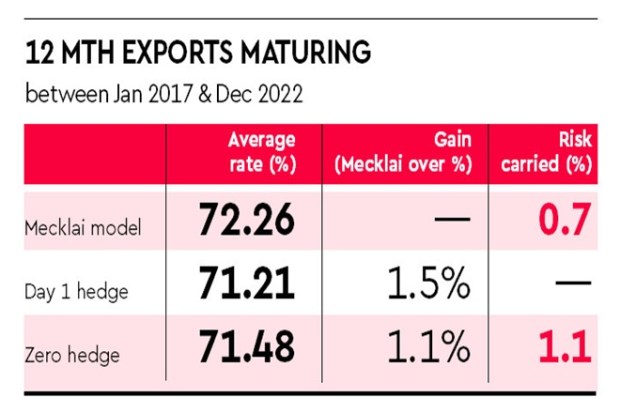

We tested this approach for 12-month exports running from Jan 2017 to Dec 2022 assuming that spot USDINR moved as it actually did but that the premiums were flat at 2.2% pa (the current level). The programmeme performed admirably, outperforming a Day 1 hedge by 1.5% and a zero hedge by 1.1%— that’s more than a million dollars any which way for $100 million of exports.

Also read: High-Priced Gender Disparity for India

To be sure, this approach did carry a certain amount of risk, given that the exposure was unhedged nearly 70% of the time. This is justified by the risk analysis discussed above, which indicates that you need to stay unhedged a reasonable amount of time to be able to capture value in this kind of market. The trick is to determine when to stay unhedged and when to take protective action.

The model seems to provide a good answer this question.

The writer is CEO, Mecklai Financial

wwww.mecklai.com