By Harsh V Pant & Vivek Mishra, Respectively vice-president, and fellow, Americas, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi

As the escalation between India and Pakistan quickly veered towards a full-blown conflict last week, the United States’ intervention came as a bolt from the blue, especially as it followed Vice President JD Vance’s statement that the India-Pakistan conflict is “none of our business”. Vance’s statement is consistent with both the US stand on the India-Pakistan dynamic since the 1999 Kargil conflict as well as with the evolving Trump doctrine where external intervention without tangible economic interests seems a policy of the past. A quickly escalating conflict where new domains of attack and counter-attack began to be tested, even as India hit multiple bases across Pakistan and showcased a robust aerial defence capability, forced the US to urgently engage both sides diplomatically.

The US’ climbdown from its earlier position of non-intervention was done to provide guardrails, especially to prevent Islamabad from its habitual recourse to nuclear brinkmanship. However, Trump’s rather curious balancing act between India and Pakistan through a tweet, hinting at Pakistan as a potential trade partner of Washington, has generated significant heat in India. If achieving a ceasefire was the immediate intention, it may be understandable. Now that the ceasefire has been achieved, Delhi should make its red lines clear to Washington, especially in relation to India’s expectations from the latter vis-à-vis the India-Pakistan dynamic.

Efforts to hyphenate India and Pakistan and the use of India-US trade relations as a lever to force undesirable outcomes from India’s perspectives may not be the best strategy for Trump. Such an approach is not congruous with the natural trajectory of India-US relations and raises questions about what the Trump administration’s own goals vis-à-vis Pakistan may be in the long term. Trump is known to harbour a strategic thinking which is transactional and unabashedly seeks economic guarantees for America’s past economic costs. The US mineral deal with Ukraine is at the forefront of that rapacious thought from Washington under Trump. As such, Trump’s hint at a future trade relations with Pakistan may have brought to fore a latent desire of a future economic deal in the Af-Pak region — where America has spent considerable money in the past three decades.

The Trump administration’s inconsistency on Pakistan had come a long way, to an extent that it now appears a normative thing in the backdrop of several policy reversals in the first hundred days of the second Trump administration. From calling Pakistan a safe haven for terrorists during his first term to hinting at a potential elevation in trade relationship may be a long arc of policy adjustment even for the Trump administration’s quintessential pragmatic embrace. In the end, no matter how the Trump administration decides to slice it with Pakistan, India’s own dynamic with Pakistan is unlikely to be impacted.

The fact that the terrorist attack in Pahalgam on April 22, in which 26 civilians were killed, coincided with US Vice President Vance’s India visit, meant there was a cognitive re-centring of Pakistan as a state sponsor of terrorism. It induced Vance’s support for India’s right to defend itself. Vance’s own relatively colder distancing of the US from the India-Pakistan conflict played into the hands of India and provided it wider operational spectrum of response to Pakistan. India’s military response in Operation Sindoor marked an inflection point in three ways.

First, it established resolute military response against terrorist infrastructure in Pakistan as the “new normal” going forward. As such, the Trump administration should assess Pakistan’s internal and external state behaviour on a metric contingent with deterring Pakistan from support to any terrorist activity in the future. Second, India has hinted that Pakistan’s nuclear brinkmanship as a strategy to deter India is likely to fail in the future.

Washington’s callousness to Pakistan “madman” approach when it comes to nuclear use should be a cause for grave concern. Putting outsized pressure on Tehran to prevent acquisition of nuclear arms while turning a blind eye to Islamabad’s rogue behaviour may be the starkest imbalance in Trump administration’s global nuclear policy. Third, by removing the difference between terrorists and their sponsors, India has not just charted its future course of response vis-à-vis Pakistan-sponsored terrorist activities but has also potentially provided the US, as indeed the world, a moment for a consensual counterterrorism framework.

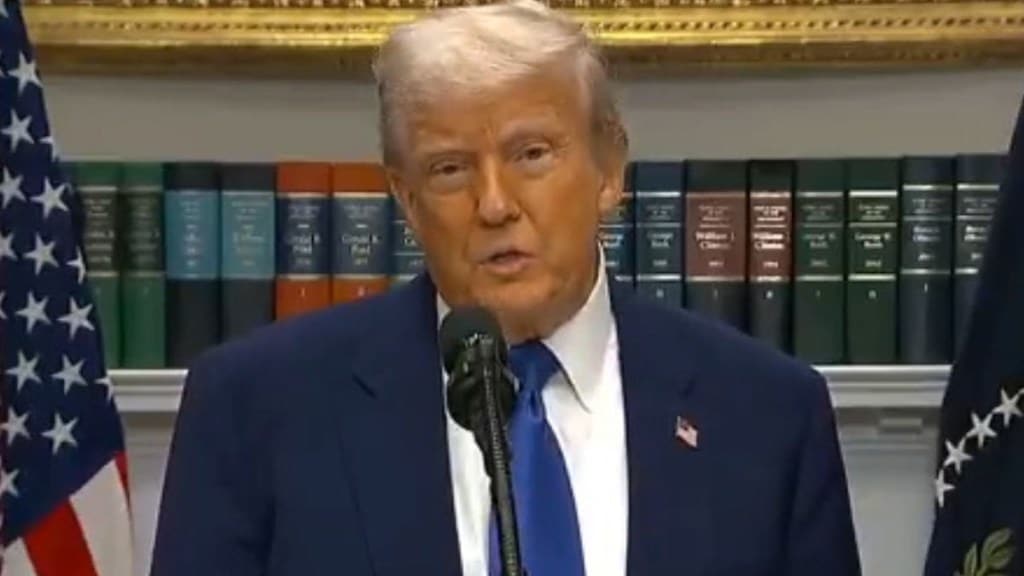

In the aftermath of the ceasefire between India and Pakistan, the quick scramble in the Oval Office to own the credit for it may have achieved its intended short-term purpose by putting the onus on the conflicting parties for a lasting ceasefire. But the fact that Pakistan continues to breach the ceasefire in a below-the-threshold manner by testing India’s aerial defence may be a point of reflection for the Trump administration’s trust on Islamabad.

In times where global diplomacy is a fickle approach, especially from the United States, and actors are left to fend for themselves, Kashmir should provide a reverse template to the world of India’s ability to handle the bilateral issue on its own. Prime Minister Narendra Modi made it clear in his address to the nation that the decision to pause Operation Sindoor was taken after Pakistan’s terror infrastructure had been “decisively neutralised”, thereby making it clear to the world at large that it is New Delhi that remains in the driving seat when it comes to it making choices pertaining to Pakistan and its malevolent actions.