By Harsh V Pant & Kalpit A Mankikar, Respectively Vice-President for Studies and Fellow, China Studies, ORF

Reports that an Indian woman was harassed and detained for 18 hours while transiting through China recently has sparked off a political storm. The woman from Arunachal Pradesh was reportedly asked to “apply for a Chinese passport” by officials at Shanghai airport during a layover. The Chinese officials’ contention was that the Indian passport of the flyer from Arunachal was not valid since the Indian state was a part of China. The woman also disclosed that she did not have any issue while her travel through China in October 2024.

The Ministry of External Affairs took issued a strong demarche to China. The government asserted that Arunachal Pradesh is a part of India, and that its residents are entitled to travel on Indian passports. This action has been followed up with the government asking Chinese authorities to give assurances that Indian nationals will not be selectively targeted while they travel or transit through China. Short of an adverse travel advisory, the government has cautioned Indian nationals travelling through the mainland to exercise “discretion”. A question on this issue posed by an Indian journalist in Beijing to a Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson has revealed Beijing’s mind. The spokesperson reiterated that “Arunachal Pradesh” had been illegally established by India, and that the territory had not been recognised by China. The spokesperson referred to Arunachal Pradesh as “Zangnan” or south Tibet. When an Indian TV anchor brought this issue to the attention of the Chinese ambassador in India, Xu Feihong, the latter endorsed the Chinese spokesperson’s stand. The envoy highlighted the issue of the contentious border, and the need for a solution in the form of a mutually agreeable boundary. Pakistan too has weighed in and supported China.

The woman’s mistreatment in Shanghai has exposed the fault lines in India-China relations. Since China tried to change the status quo along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in 2020, India’s response was that it would not be business as usual. Cultural, educational, and business cooperation became a casualty of the military coercion, and visas for journalists were revoked. Beijing’s rejoinder to these actions was that the border issue should be put in its “rightful place”, meaning that people-to-people connection should not be contingent upon the border situation.

Normalisation Derailed

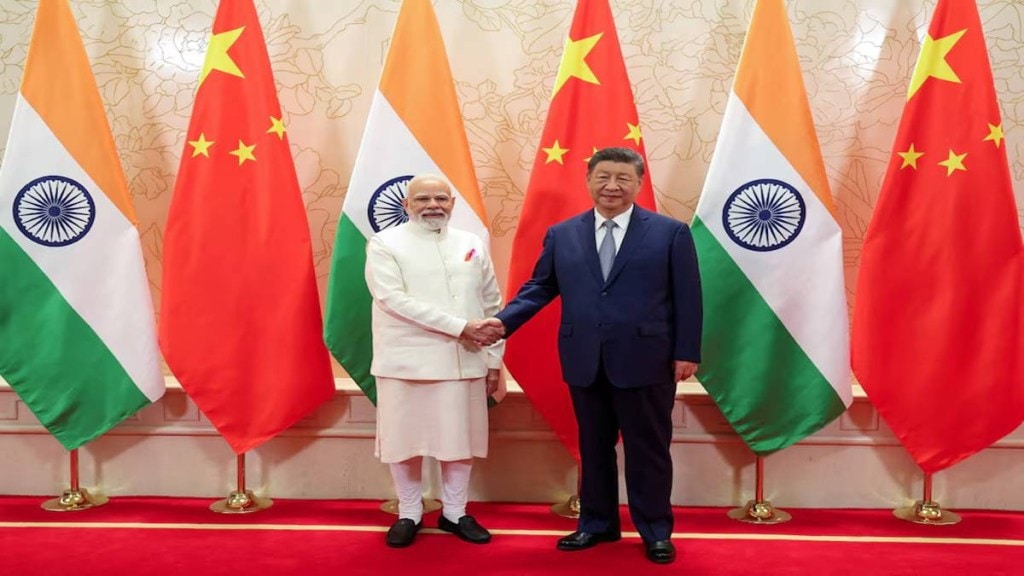

Following Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping’s meeting in October 2024 during the BRICS summit in Russia, both nations embarked upon a path of cautious normalisation. By agreeing to patrolling arrangements along the LAC, Beijing tacitly admitted to trying to change the facts on the ground through military coercion. The accord reached with China in October 2024 fulfilled an important aim—getting Indian troops to again patrol the relevant points, and resuming pasture grazing. With patrolling resuming along the LAC, it provided a convenient segue into taking people-centric steps to stabilise the relationship. This premise resulted in the resumption of the Kailash Mansarovar pilgrimage, the visa regime being liberalised, direct flights resuming between Indian and Chinese cities, and exchanges between news organisations and think tanks. In fact, this year marks the 75th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two nations, and both sides had resolved to prioritise efforts through public diplomacy to restore mutual trust. Yet a single incident has cast a dark shadow on the India-China dynamics. This time around, in a seeming volte-face from its previous position, it is the Chinese that have brought forth the primacy of the border, which they all along insisted should be put in its rightful place.

While some commentators in India have sought to pin the blame on zealous immigration officials in China, and view this as a localised problem, there is a discernable pattern to this sudden shift in the Chinese position. Things have come to a head between Beijing and Tokyo after Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi merely expressed her nation’s standard position that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan would mean an existential crisis, and that its self-defence forces would have to intervene. Takaichi’s statement during a parliamentary debate has sparked off a crisis between the two nations. China’s wolf-warriors are back with one diplomat threatening to “cut off the dirty neck”. Chinese nationals were told to avoid going to Japan, which led to an estimated 500,000 flight tickets being cancelled. China has reinstated a ban on Japanese seafood imports.

The war of words has resulted in Xi’s call with US President Donald Trump, where he aired his grievances about Tokyo and Taipei. In turn, Trump reportedly told Takaichi to avoid needling Beijing over Taipei. Trump cosying up to Xi could be motivated by his eagerness to reach a trade deal with China, for which he has even dangled the prospect of a “G2” compact. Washington’s overtures for a détente with Beijing perhaps explain China’s sudden belligerence in territorial disputes with neighbours India and Japan. Additionally, the National Security Strategy of Trump 2.0 delineates the Western hemisphere as a vital interest, and in this pivot to its neighbourhood China may see a shrinking role of the US on the world stage. This may have emboldened Beijing to probe around and carve out its own “backyard”.

The strain following the Shanghai airport incident comes at a time when New Delhi is mulling over reviewing the relaxation of investment controls, specifically Press Note 3, which had been brought in to regulate capital inflows from nations that share a land border with India. China’s renewed vigour in using economic coercion in territorial spats will indubitably shape India’s approach as it seeks new terms of economic engagement. Beijing’s recent posture is signalling that a buoyed China sees no reason to divorce its strategic posture from its economic one.