By Santosh Mehrotra & Jajati Parida

Claims by the Union government and certain economists about employment creation and wage growth in recent months have mounted, just as evidence has simultaneously mounted that such claims don’t stand up to scrutiny. This piece is focused on a debate that has raged in recent months in The Indian Express about recent real wages trends.

However, to understand these economists’ claims in context, another set of claims also need to be mentioned. A first claim was that India is experiencing “A ‘Jobful’ Economy”; another was that wages have been rising; and yet another was that India does not need to create many jobs as there is mismeasurement of the numbers joining the labour force as population growth rate has fallen. I have demolished the first and third claims earlier.

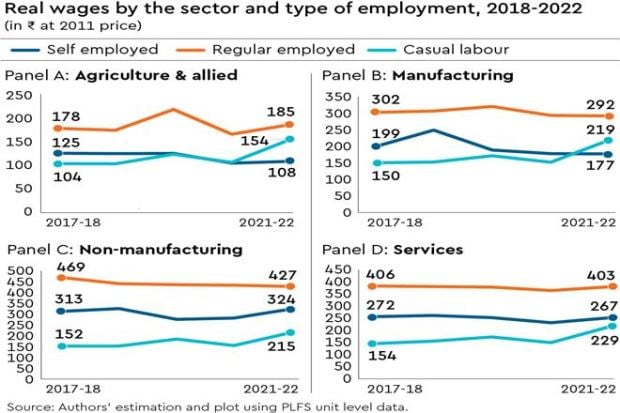

I want to elaborate on the second claim, which also do not stand up to scrutiny when we examine—based on the Periodic Labour Force Survey (NSO)—the entire workforces’ wage or earnings data. The wage data for wage workers (casual or regular) or earnings data for self-employed—whether it is in agriculture, manufacturing, non-manufacturing (including construction, mining, utilities) industry, and services—demonstrates that wages and earnings have stagnated for the last five years (see graphic). This finding needs to be read with the fact that National Survey Organization’s (NSO) Employment-Unemployment Round between 2004-5 and 2011-12 had shown an unmistakable and sustained rise in real wages over that period. However, they stagnated between 2013 and 2017.

It is fairly easy to understand why real wages across sectors, and across work categories, in the economy have either stagnated or fallen over the last five years. FY18 was the fiscal year that followed the demonetisation (late-2016) move, which had caused widespread damage to large parts of the economy, especially agricultural incomes as well as the entire unorganised sector of the economy; the latter is spread across all economic sectors.

Just as the economy emerged from the demonetisation, a poorly designed Goods and Services Tax (GST) was introduced in July 2017, which subsumed 17 other central and state taxes. The GST had not been sufficiently tested, and the computer software and systems were simply not ready; it caused widespread disruption, again to the unorganised sector, and especially to the MSMEs, which were even less prepared to make the transition to an ill-prepared GST machinery’s implementation of such a tax. Inevitably, the economy went into a gradual slowdown, with GDP falling in every quarter continuously till the pandemic.

Joblessness had reached a 45-year high in 2017-18 itself; with the continuous slowdown in the economy, joblessness continued to increase. The total number of unemployed was 10 million in 2011-12; it rose to 30 million by 2018-19, the last year before Covid broke.

The pandemic began with a lockdown announced at four-hours notice for nearly 1.4 billion people, with the entire economy and transportation brought to a standstill. The lockdown was national in scope; not so in China, where it was confined to Wuhan (capital of Hubei province) first, where the Covid virus was first detected, then in the province. India’s was the strictest lockdown in the world, according to the Oxford University Blatavnik School of Government’s international metric for measuring stringency of lockdown measures; our lockdowns remained among the strictest in the world, even though 80% of cases in July 2020 were in nine big cities.

The economy contracted by 6.6% in FY21—in the first year of Covid when the world economy contracted only 3.1%. China’s GDP grew in that year. If we recovered in the following two years from an extremely low base, then it is not surprising that India, already the world’s second-fastest growing large economy for 15 years, became the one growing fastest for the following two years upto 2022-23. The RBI, in an early 2022 study, had said India’s economy will not recover to its original growth path till 2034-35.

Poor economic management continued fuelling rising inflation, compounded by the Union government’s high taxes/cesses on fuel, which stoked inflation further; no amount of recent monetary tightening (before the RBI paused) after sustained monetary easing during the Covid years has brought inflation down to within the central bank’s target rate of <6%.

If real wages fell or stagnated, as joblessness grew further, to nearly 38 million in 2022, it is not surprising. At the same time, CMIE rightly reported that workers were falling out of the labour force, i.e. had stopped looking for work. The employment rate (or worker participation rate, which is the share of working age in the population with work) fell from 43% in 2016 to 36% in 2022, and has only just climbed back to 37%. Youth unemployment had already doubled or tripled, depending on your level of education between 2012 and 2020-22. Hence, if real wages stagnate, it is exactly what is expected.

The authors are Respectively, visiting professor of economics, University of Bath, UK, and associate professor of economics, University of Hyderabad