Expect the RBI MPC to roll back at least 25 bps of its cumulative 50 bps rate hike this year on February 7 with Governor Das seeing the inflation outlook as ‘benign’. It is better to act in February rather than April as the ‘busy’ industrial season will end by March. The Centre would also have presented its vote on account by then. The RBI rate cut call is based on the assessment that there is no material risk of high inflation over the next 6 months. Base effects will drive inflation above 5% in H2FY20, even assuming an underlying FY20 inflation of 4.5%. We see inflation averaging 3.2% in December-March at the lower end of RBI’s 2-6% inflation mandate. Although the RBI MPC hiked 50 bps, most EM central banks actually eased in 2018.

Slow sowing (down 5.2% y-o-y) is a concern. However, Bhakra/Pong /Thein dam water levels, which irrigate winter wheat, at 84/74/71%, are higher than 72/57/ 43% last year. It is NRI bonds, raising $30-35 billion, rather than rates hikes, that will fend off depreciation risks. It is estimated that 1% depreciation results in 15-20 bps of inflation over time. In any case, ` should also get some seasonal support in the March quarter. Oil strategists see $70/bbl in Q1FY19, up 3.7% from Q1FY18’s $67.5/bbl.

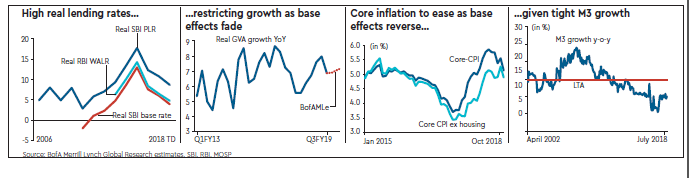

High real rates are hurting growth. With H2FY19 inflation set to average 3%, the ex-post real policy rate/1-year T-Bill rate would rise to 3.5/4%, well above RBI’s 1.25-1.75% band (it is preferable to see real rates ex-ante though). Not surprisingly, GVA growth is slipping to 7% levels from 8% in June with a liquidity crunch aggravating base effects. By adjusting for base effects and by taking averages of the September 2017-18 quarters, growth works out to a 6.5%, well below the 6.9% average of even the new GDP back cast series.

Incoming data supports the view that the RBI MPC’s inflation risks are overdone. December inflation is at 2.4% atop November’s 2.3% on low agflation. In fact, the RBI MPC has, yet again, cut its H2FY19 inflation forecast to 2.7-3.2% from 3.9-4.5% earlier and estimated H1FY20 inflation between 3.8-4.2% from Q1FY20 estimate of 4.8% in October. It is on base effects that inflation climbed to 4.9% in June (as it will cross 5% in H2FY20). It has naturally eased as they fade.

Core inflation will similarly come off as base effects fade. Fundamentals do not support higher core inflation. Weak growth prevents corporate pricing power. Just as importantly, an excessively tight monetary policy has also sustained high real rates that keep both growth and core inflation in check. Food deflation has surprised on the downside. That said, even if the food price trajectory had been as expected, inflation would have hovered around 4.5% range, well within RBI’s 2-6% mandate. The RBI MPC’s concerns about hikes in minimum support prices (MSPs) fuelling inflation are unfounded as most of the revised prices are below market prices. Markets are also likely pricing in lower growth expectations which should reduce “imported” inflation pressures. It is hardly likely that fiscal slippage of, say, 40 bps of GDP will fuel inflation in an economy that is operating below capacity. In any case, the Centre’s fiscal deficit, at 3.7% of GDP, is well below the long run average of 4.5%. The RBI MPC’s concerns about ‘second’ round impact of hikes in housing rent allowances (HRA) recommended by the 7th Pay Commission for the Central and state governments are also unwarranted, given that a large number of these employees stay in government housing, making the HRA hike purely notional.

Expect the RBI MPC to proactively support domestic demand when global growth is slowing. BofAML economists have pared their global growth forecast to 3.6% in 2019 from 3.8% in 2018 and their US economists have just cut their 2019 Fed hike forecast to 50 bps from 100 bps after the Fed’s dovish hike last night.

RBI has defused the on-going liquidity crunch due to delayed OMO in face of sustained FX intervention with its `1.5 trillion OMO calendar. BofAML’s liquidity model estimates that it has to inject about $30 billion of durable liquidity in FY19. Their balance of payments estimates forecast RBI FX intervention at $26 billion even if FPIs end FY19 flat. RBI would have conducted/announced OMO of $25 billion. Adjusted for the Centre’s buyback of $5.5 billion, it has to OMO about another $25 billion/`1.8 trillion by March. This should be broadly met with the RBI OMO calendar for the March quarter. Even after the RBI’s `500 billion OMO, the money market will likely end with a deficit of `750 billion in December.

The author is India economist, DSP Merrill Lynch (India)

Edited excerpts from BofAML’s India Economic Viewpoint (Dec 20)

Co-authored by Aastha Gudwani