By Emmanuel Thomas & TM Jacob

The National Institutional Ranking Framework’s rankings have become the IPL of higher education! Each year produces its champions after an exhilarating run by the participating higher educational institutions (HEI), whose numbers have risen from 233 universities and 803 colleges in 2017 to 294 and 1659, respectively, in 2020. There are about 1,000 universities and 40,000 colleges in India. The ranking framework evaluates institutions on five parameters: Teaching, Learning & Resources, Research & Professional Practice (RP), Graduation Outcomes, Outreach & Inclusivity (OI) and Perception (PR).

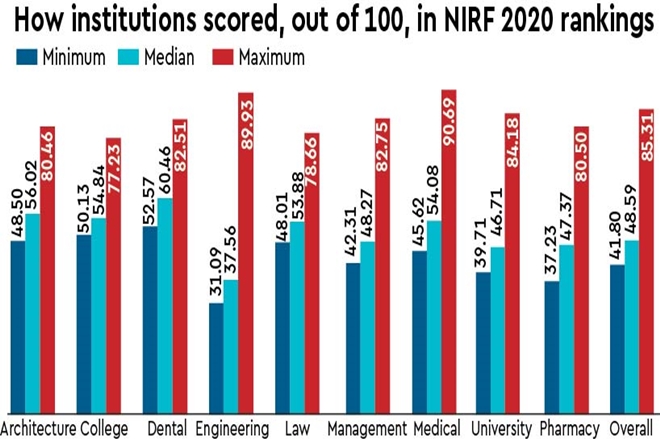

As seen globally, there is a predominance of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) in the top ranks. In the ‘Overall’ category, while the score ranges from 42 to 85, there are only 13 institutions with a score above 60, and IITs and the IISc make eight of them. With the scores being highly skewed, it is really a rarefied world at the top. In the ‘University’ category, the scores of top 100 range from 40 to 84. But an overwhelming 65 universities have a score below 50. With this clustering of institutions at the tail, most of them miss it narrowly. Regional inequality, too, is glaring, and 42 of the top 100 universities are from three states: Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Karnataka. Similarly, 81 colleges in the top 100 are from Tamil Nadu, Delhi and Kerala. But in a winner takes everything mode, pumping resources only to the winners will widen the gulf.

As argued in an opinion piece ‘Perils of Chasing Indicators’ (bit.ly/2BetyXn) on NIRF 2019 in this newspaper, rankings attempt to introduce competition between institutions operating in quasi-market environments. It is laudable that the government is generating a credible benchmark through the NIRF. It is also noteworthy that it is mostly based on objective indicators. The PR parameter, which is widely criticised in rankings literature as ‘reputation’, is given only a small weight of 10%.

Nevertheless, there are unintended consequences of measurement. Jerry Z Muller in his 2018 Princeton University Press book ‘The Tyranny of Metrics’ argues that anything that can be measured and rewarded will be gamed! He mentions a school in the HBO series ‘The Wire’ that is facing the danger of closing down if students perform poorly in English test. The school principal asks all teachers to devote the remaining time for preparing students for the test, ignoring all other subjects and activities. This strategy is euphemistically called ‘curriculum alignment’. ‘Teaching to the test’ is one way in which institutions get perverted in reality, attempting to achieve something in letter, ignoring the spirit. Hence, as Phil Baty of Times Higher Education (THE) ranking says, “ranking should inform decisions and never drive decisions.”

Often, rankings force institutions to mimic the best performing ones, albeit without any real impact. What are needed are heterogeneous institutions with varied missions, programmes and approaches. There are differences between types of institutions too in terms of their functions and objectives. But the parameters and the assigned weights can distort the perception of agents.

For example, the core function of colleges is to produce graduates with a strong base in their subjects. Hence, the NIRF assigns a higher weight for teaching in colleges. Still, colleges coax teachers, who are inclined to teaching, to increasingly do research and publish for which they are ill-equipped. A 16-hour teaching load, and the task of conducting all the programmes to score on various ranking parameters and maintenance of an MIS fall squarely on teachers. It is apt to recall the words of the pro-vice chancellor of the University of Hamburg, who while opting out of the CHE Ranking, stated that it takes the work capacity of 12 people to do all the required work for ranking and that the task of the university is to provide good education. Faced by these constraints, teachers resort to low-quality research, for which the mushrooming of predatory journals in India is the living proof. In this process, colleges end up compromising on something that is difficult to measure—teaching.

According to education researchers, one major factor that helps students graduate is ‘student engagement’. An important aspect of this engagement is the quality of contact with faculty. In fact, it is this aspect that enriches the career of a teacher too. This is severely affected in colleges due to the above said burden on teachers.

It is certainly encouraging to see HEIs in India responding to the rankings framework. Given this response, the policymakers should innovate and modify the metrics suitably. One, there is an urgent need to modify the metric by including feedback from teachers. Students will definitely benefit by studying in institutions where teachers are happy and their job satisfaction level is high. Two, rankings on the basis of different parameters should be published. Although some data is available on the website, official publication of such rankings will help students make more informed decisions. Three, there is a need for use of ‘specialisation index’ in relation to publication. Currently, publication is considered at institutional level. One or two faculty members can lift the score of an institution. Four, the use of PhD as a measure of quality of faculty is fraught with serious drawbacks, for the quality of PhD varies a lot. A better indicator, at least for non-university categories, would be UGC-CSIR-NET. Five, a component metrics under the OI parameter ‘% of students from other States and countries’ clearly favours HEIs in the metros. Six, the NIRF should increase the number of ranked institutions gradually as institutions are improving their scores. The score of 100th ranked college is 50 in 2020 compared to 35 in 2017.

Meanwhile, it is also important not to get carried away by rankings. The performance of HEIs depends crucially on the higher education system. Universitas 21 (U21), a consortium of universities, of which the Delhi University is a part of, ranks 50 higher education systems using 24 measures of performance grouped into four modules—resources, environment, connectivity and output. In its latest ranking, India is ranked 49th with a score of 39.6. All other BRIC countries are ahead of India. Interestingly, countries like Iran, Turkey and Ukraine also rank better than India! This points to the need for urgent government action.

Moreover, on the lines of IPL, the government should make these rankings global. That will help us find out where our institutions stand. Only eight Indian institutions are there even in top 100 of the THE Asia Rankings 2020. There is a long way to go.

Thomas is doctoral fellow, CESP, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and assistant professor, St Thomas’ College (Autonomous) Thrissur; Jacob is associate professor, Nirmala College Muvattupuzha, Kerala. Views are personal