By Ashok Gulati & Ritika Juneja

India is today a $3.5 trillion economy, and if the present growth trend continues, it is likely to become a $5.4 trillion economy by 2027 (as per IMF forecast). The Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict have thrown the global economy into a spin, and India’s ambitious target of becoming a $5 trillion economy by 2025 is going to get somewhat delayed, but is not entirely out of reach. India seems to be on the right path and doing pretty well, especially compared to its progress over the decades since 1947.

Consider the following:

As per IMF, it took India almost 59 years after its Independence to become a $0.95 trillion economy (in 2006). But, then it became a $2.3 trillion economy by 2016, thus adding $1.35 trillion in 10 years. And, in 2022, it became a $3.5 trillion economy by adding $1.2 trillion in just 6 years. If India stays this course, it is very likely that it will rise to a $25-30 trillion economy by 2047. No wonder, prime minister Narendra Modi has termed this coming period as amrit kaal when India completes its 100 years of Independence.

But there are two issues that we want to focus on. First, how inclusive is this growth, and second, how sustainable it is likely to be, especially from the environmental angle given that climate change is already knocking on our doors.

We measure inclusiveness by looking at the performance of the laggard states, especially the so-called BIMARU states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh), and also of the agricultural sector that engages the largest share of work force (46.5% in FY21). It is a fact that as development proceeds, the workforce moves out of agriculture to higher productivity jobs in urban areas, especially in construction of new cities and infrastructure required to run those cities. More than half the world’s population today lives in cities, though India is still roughly two-thirds rural. So, during the next 25 years, India’s focus should remain on construction of infrastructure, including rural, and skilling our large mass of working population for higher productivity jobs. The Union Budget of FY24 has surely done well on this account, and finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman deserves our compliments for that.

Let us look at the performance of the GDP at the state level—the agriculture sector in particular—between FY06 to FY22, for which we could get the latest data at the state level from the ministry of statistics and programme implementation, cutting across the UPA and NDA governments at the Centre, apart from the various political dispensations in power over the period at the state level.

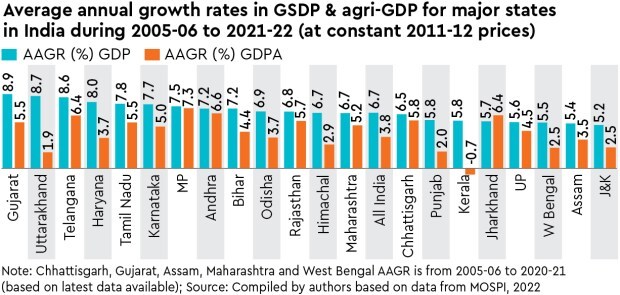

The accompanying graphic shows that, at the national level, overall GDP growth stood at 6.7% per annum and agri-GDP growth at 3.8% per annum over this period. This is quite satisfying, though not as outstanding as China’s. Among the major states, Gujarat topped the list in overall GDP growth at 8.9%, closely followed by Uttarakhand (8.7%), Telangana (8.6%) and Haryana (8%), all scoring 8% or higher growth. At the bottom end were Jammu and Kashmir (5.2%), Assam (5.4%), West Bengal (5.5%), Uttar Pradesh (5.6%) and Jharkhand (5.7%).

In order to see how inclusive this growth has been, we look at agri-GDP growth in the BIMARU states. Interestingly, Madhya Pradesh (MP), one of the BIMARU states, has performed outstandingly well, clocking the highest growth rate in agriculture at 7.3% and overall GDP growth of 7.5%. Its agri-GDP growth of 7.3% is not only much above the all-India agri-GDP growth of 3.8%, but is also a shining example of the contribution of horticulture, which has doubled in its value within the agriculture and allied sector. MP has made its mark by being the top player in tomato, garlic, mandarin oranges, pulses (especially gram) and soyabean. Pulses and oilseeds are nitrogen-fixing and use very little water, thus saving outgo on fertiliser and power subsidies, and ensuring environmental sustainability. MP is also the second-largest producer of wheat (after UP), and third largest producer of milk (after UP and Rajasthan). It is following a well-diversified portfolio in agriculture, while its doubling irrigation ratio from 24% to 45.3% of its gross cropped area over the last two decades. As a result, MP is the only state where agriculture’s contribution to the overall GDP has increased to 40%, as against 18.8% at all India level. Call it an inclusive and sustainable growth model.

Among other BIMARU states, Rajasthan has also done very well in agriculture, recording an annual average growth rate of 5.7%, followed by UP and Bihar with 4.5% and 4.4%, respectively.

Two other states need special mention when it comes to agriculture: Jharkhand and Punjab. Jharkhand, which was carved out of Bihar in 2000, has performed exceptionally well in agriculture with a growth rate of 6.4% per annum, largely driven by diversification towards horticulture and livestock. Punjab, the hero of Green Revolution, has been sliding down, and its agri-GDP growth was a meagre 2% per annum over this period. We know that proud Punjabis will say that Punjab already stands at a higher level of productivity of wheat and rice, and therefore further higher growth in agriculture is not feasible. With all humility, we have to say that this is not correct (both of us are proud Punjabis). If Punjab had diversified to high-value horticulture, or even some pulses and oilseeds, it would have registered higher growth in agriculture and, more importantly, it would have saved on precious groundwater, power subsidy, and methane and nitrous oxide emissions from paddy. Something for Punjab’s policy makers-to pause and think.

Ashok Gulati & Ritika Juneja, respectively, distinguished professor, and research fellow, ICRIER. Views are personal.