By Saugata Bhattacharya

That the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) would hold the policy repo rate—unanimously—at 6.5% was a foregone conclusion, as was the (likely) 5-1 vote to maintain the “focused on withdrawal of accommodation” stance. The global macro-financial environment, and hence, domestic financial conditions and the continuing risks of inflation remain too fluid for any material change.

In the context of this status quo in policy action, to my mind, there was a subtle hardening in the language and idiom of the statement. The assertion that “monetary policy must continue to be actively disinflationary” was articulated for the first time. This suggests, and is reinforced by public comments, that inflation control remains the primary objective of monetary policy, even as it continues to support growth. This is justified by multiple underlying trends.

One, the large increase in the RBI’s growth forecast, from the earlier 6.5% to 7%, was the biggest surprise in this policy review and testifies to the RBI’s assessment of resilient demand conditions and disposable incomes. The average CPI inflation rate for FY24 was retained at 5.4%, and thereafter is projected to fall only gradually in FY25. Read together, in addition to the frequent mentions of food inflation risks, there is also the latent risk of a creep-up in (non-food and fuel) core inflation. While crude oil prices have softened recently, in anticipation of slower activity in developed markets, expected OPEC+ output cuts remain a concern on pass-throughs into transport and agri-input costs.

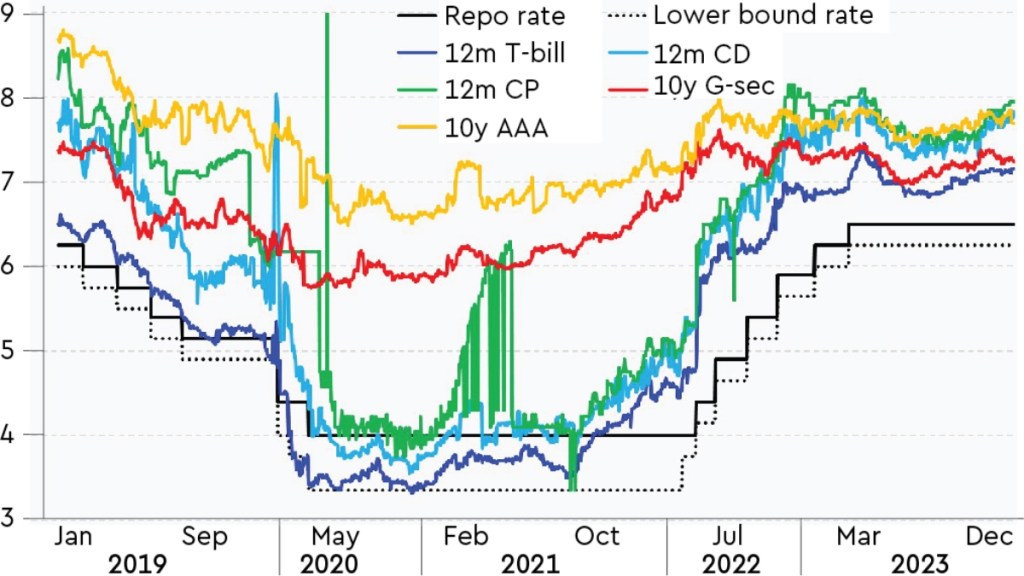

Second, the domestic financial conditions have eased significantly since the last review. In particular, equity markets remain buoyant, and retail investors’ participation has increased significantly. Hence, the consequent wealth effects could potentially add to demand, especially in smaller urban agglomerations that are adding to the investors base. While corporate profits have moderated in some sectors, they still remain robust. Bond yields in India have also come down, although not materially. Globally, markets have begun to price in G-10 central banks rate cuts in 2024, which will result in a “risk on” environment leading to large portfolio flows into emerging markets.

Third, despite RBI tightening macro-prudential norms on banks’ and NBFCs’ unsecured retail lending (and banks lending to NBFCs), bank credit to these segments remain robust (although it is still early days). This credit flow is adding to demand, and transmission in credit markets remains incomplete. This indicates that liquidity conditions will continue to be held tight. Government spending and consumption remains high.

What can we expect of monetary policy going forward? RBI’s growth and inflation forecasts suggest that any policy repo rate cuts will not be feasible for the most part of FY25. Average growth over Q1-Q3 FY25 is projected at 6.5% and average CPI inflation at 4.6%, not exactly a growth-inflation tradeoff necessitating an easing of policy.

Globally, the extreme uncertainty which had characterised economic activity, soaring inflation and the synchronised G-10 central banks rate hikes over 2022 and 2023, has eased to a large extent, but financial markets remain volatile. It is now widely expected that the US will be able to manage a soft landing. US November Non-Farm Payrolls data and the forthcoming Federal Reserve FOMC meet will provide guidance. The major Euro Area economies are also expected to recover, although performance is lagging the US. In Germany, consumer confidence remains weak, automobile production is down and the Manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index continues to be in contraction, but retail sales seem to be improving.

Europe had remained much more fiscally conservative than the US, but ongoing negotiations have opened the possibility of a fiscal stimulus. However, signals remain mixed and incoming data and policy statements will provide more clarity in the coming weeks and months. One of the outcomes of this evolution will be volatility in the major currencies, which will affect the rupee. China remains another source of risk, although the economic slowdown there seems to have bottomed out, and exports have once again begun to expand.

While India’s macro-financial conditions remain very resilient, it does remain exposed to global volatility. Hopefully, the slowdown in India’s exports, both merchandise and services, have bottomed out. However, as the policy statement emphasises, domestic demand conditions remain strong, rural demand seems to be recovering, the current account deficit (which I forecast at 1.7% of GDP in FY24) is manageable, the RBI has sizeable foreign exchange reserves, and corporate and financial sector balance sheets remain strong.

While the MPC remains focused on bringing down CPI inflation durably lower to the targeted 4%, the RBI is turning towards issues of potential financial instability and pro-actively monitoring potential segments of concern.

The policy repo rate is expected to hold for awhile, but a combination of targeted macro-prudential tightening, calibration of system liquidity and exchange rate stability will add to the policy toolkit for balancing the tradeoffs in the multiple macro-economic objectives.

The author is a Mumbai-based economist.