No one envies the MPC members for their extended three-day bi-monthly meeting from June 4-6. The hawks are out in droves; the doves would rather forget this spring of discontent. It was, what, just seven weeks ago, after the April 7 MPC meeting, that the cry went out from the ramparts of RBI—no rate hikes as far as the eye can see. We all hung up our inflation boots and celebrated the oncoming summer lull. For all of two weeks.

On April 21, the same MPC that had lowered inflation forecasts for the first half of the fiscal year by 45 bps (from a 5.1-5.6% average to 4.7-5.1% for H1FY19) now revealed that, in its deliberations, it had actually “felt” the opposite. In particular, one MPC member, Viral Acharya, more or less declared the rebirth of accelerating inflation in India, something his colleague, Michael Patra, has been warning about since he voted for a rate cut at the inaugural MPC meeting of October 2016.

Barely had the Viral shock worn off that the markets were hit by something truly viral—inflation data for April, released on May 14, indicated a 100 bps increase in core inflation excluding housing over the March y-o-y inflation of 4.4%. Indeed, Acharya had hinted at this particular measure of inflation as a “target” for monetary policy in the minutes of April Monetary Policy released on April 21.

There are several battles being fought here. I also think that headline inflation as a target is problematic. Indeed, my preference for an inflation target is the deflator of private final consumption expenditure (PFCE), something quite common in many parts of the advanced world, especially in the most advanced economy, statistically and otherwise, the US. If the PFCE were to be used (and note that we don’t have to worry about excluding food, or fuel, or petrol, or housing, or vegetables or any of the other exclusions policy makers dream of).

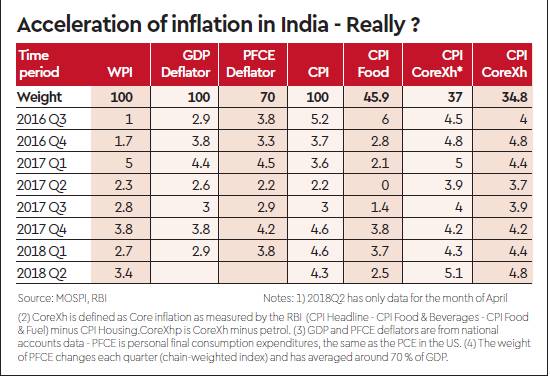

This inflation indicator shows the following trend for the last five fiscal years, starting in FY14: 7.5%, 5.3%, 3.9%, 3.8% and 3.3% (see table). Yes, 3.3% in FY18 is lower by 50 bps than the demonetisation year of FY17. We apologise, we digress. Back to impending viral inflation in India. The 100 bps increase in core inflation is only according to RBI’s wrong definition of core, i.e., excluding food and fuel. But, in India, petrol (what is considered fuel in most parts of the world, and not the price of kerosene or electricity) is part of transport and communications, and as far back as December 2014, then RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan had pointed out the “havoc” that just 2.4 % of the consumption basket—the consumption weight of petrol—could cause.

In the December 2014 Policy Statement, he stated “Further softening of international crude prices in October eased price pressures in transport and communication”; in the December 2015 PS: “CPI inflation excluding food, fuel, petrol and diesel” (emphasis added). The domestic price of petrol rose by 9% y-o-y in April 2018. Incidentally, the price of Brent crude rose by 44% y-o-y! Anyway, while crude is 2.4% of the overall CPI basket, it is a whopping 6.4% of the basket of goods that Acharya claims should be the inflation indicator.

As he stated in the minutes of the April 7 meeting—the one that set the cat amongst the doves—“What concerns me is that the more persistent component of headline inflation, which is ex food and fuel, and which one can consider as the “signal” given its persistence, has strengthened steadily from a trough of 3.8% last June to 4.4% in February (excluding the estimated impact of Centre’s House Rent Allowance increase, i.e., ex HRA). This rise has been broad-based…”

Nowhere does Acharya, or any other member of the MPC, point out that petrol should not be included in core excluding housing (CoreXh).

If they were to do that, they would find that while acceleration in CoreXh inflation was 100 bps, it was some 40 bps lower for CoreXh excluding petrol (CoreXhp). How did just 2.4% weight inflating at 9% cause such a large difference—very simple. A 2.4% weight in overall CPI is a highly magnified 6.4% in a reduced CoreXh weight of just 37% of aggregate CPI. Yes, that is correct. Core CPI is 47% of the basket, and housing is 10%, so CoreXh is 37%. Given this small size of the inflation universe, even a wiggle can cause large distortions, as we document next.

On February 1, as part of the Union Budget presentation, the government strayed from its commitment to an open economy, and imposed (debatable, controversial, and unexpected) customs duties on a wide array of consumer goods. Most of us thought (including some members of the MPC) that this will have a small impact on inflation, but given the volatility in other segments, e.g., food, that the effect will be swamped.

As documented in detail by A K Bhattacharya in the Business Standard (Budget decision on customs duty hike to impact imports of $85 billion in a year, February 12, 2018) the duties were slapped on $85 billion of goods. For our purposes of impact on inflation, we can ignore the import of diamonds and jewellery (it may have mattered to Nirav Modi, but he is absconding!) amounting to about $55 billion.

The import duty increase for most of the $30 billion of import items was 10%. Total consumption in FY18 was Rs 96.3 trillion (we know that from the GDP data released on Thursday) and the rupee averaged 65 to the dollar in FY18, i.e., total consumption of $1,480 billion, making the import items directly hit by customs duty equal to about 2% of total consumption.

Assume an average inflation rate of 4.5% for all goods and services; if 2% were to have an inflation rate of 10% (as likely happened in April when customs duties were passed on to consumers—legally the import duties became effective from February 2, but there are leads and lags in trade—and 98% an inflation rate of 4.5%, then simple maths shows that the customs duties will cause inflation to increase by 11 bps. That is too little to worry about, you say? I agree. But now look at its effect on CoreXhp (core minus housing minus petrol), an aggregation that is only 35% of the total basket.

In this case, 11 bps becomes 11*100/35 or 31 bps—which means that the acceleration in core inflation of 100 bps is now really 100-40-31=29 bps. Does that justify concern about hiking rates to stave off impending inflation, as some economists are arguing? Should RBI be unduly concerned about an 11 bps increase in headline inflation, which is its mandate? The MPC Act categorically states that it is the headline inflation, and only headline inflation, that should be the inflation target. Maybe, it is time to revise the target—but please make it the PFCE.

It will make the computation simpler, and prevent economists, analysts, and policy makers from poring over multiple numbers, and multiple inclusions and exclusions due to special effects (e.g. exclusion of the effects of Housing Rental Allowance as officially done by the MPC). One final point for keen observers of inflation, including the MPC. There are two reasons why the headline inflation target of the MPC is lower in the second half of FY19 than the first half.

The first is the diminishing of the HRA effects in the second half. The second are base effects. A reminder—the six y-o-y CPI inflation numbers from April 2017 to September 2017 were 3%, 2.2%, 1.5%, 2.4%, 3.3%, and 3.3%. In other words, the worst of the base effects are yet to be registered! Economists have published their estimate of the base effect for April 2018—widely assumed to be at least 25 bps. This implies that there was virtually—no, objectively— little genuine, demand-effect, inflation acceleration in April 2018.