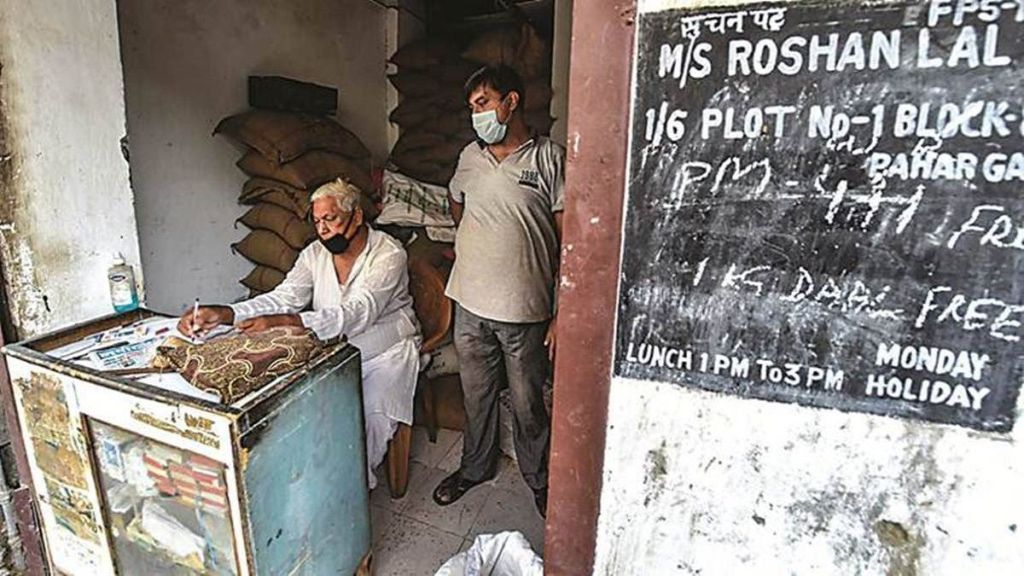

The extension of the free-ration scheme—Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY)—for another five years isn’t a surprise. A decade after food security was made a legal right and the beneficiaries and their entitlements were defined under law, basic nutritional requirements of large sections of the Indian people can’t still be met without direct budgetary support. The National Food Security Act, 2013 provided for revision of the subsidised “issue prices” of grains “in three years” from the commencement of the Act; it also states that that the Centre would review the level of subsidy “from time to time.” While the needy 813 million people were identified in 2013 on the basis of the now-outdated 2011 census, there was an implicit plan to periodically review that number.

The idea obviously was to bring down the extent (quantum) and scope (number of beneficiaries) of the subsidy as and when income levels rise. An open-ended fiscal cost spiral was meant to be avoided. However, not only has a downward revision of the subsidy in real terms not happened, but also the budgetary expenses on this front have only risen since, because real income levels of the beneficiary population stagnated. So, annual food subsidy (Rs 2.25-2.5 trillion at current prices) is now as high as 6% of the Union Budget, and tends to rise further in the coming years, constraining capital expenditure and allocations for other social-sector development projects. MSP increases and grain procurement for the central pool have in fact been calibrated, but still jacked up economic costs of grains and widened the gap with (fixed/declining) issue prices under NFSA.

On top of that, Covid distress necessitated additional food security support to the target population—PMGKAY, launched in April 2020, doubled the quantity of subsidised grains to 10 kg per person per month, and cost the exchequer a whopping `3.9 trillion before the extra-grains component ended on December 31, 2022. For sure, the current PMGKAY (free ration), which is subsumed in NFSA, adds only 5-7% to the food subsidy budget. What is worrisome is the chances of a cut in subsidy anytime soon looks even slimmer now. As fractions of the Union Budget, both food and fertiliser subsidies are likely to rise inexorably. Elevated demand for MGNREGS work, subdued rural consumption and high-level of joblessness across rural and urban areas reflect persistence of distress.

To be fair, the Modi government has done well to address the food security concerns of the poor during the pandemic. Even amidst acute fiscal constraints, it could also take the bold step of paying off the Food Corporation of India’s (FCI) Rs 3.39 trillion debt in FY21. Funds releases to the FCI have been rather prompt in recent years, but given the enormity of the task, the corporation aims to raise Rs 1.45 trillion, including ECBs, this fiscal, casting clouds over fiscal-transparency path. Public food stocks have been beefed up to ensure that NFSA supplies aren’t disrupted, even though this entailed considerable fiscal cost. Mitigation of food management costs via open market sales of grains from public stocks haven’t always been easier. However, the NFSA-prescribed life-cycle approach—which involve a diversified food basket, instead of just grains—would need to pursued to meet the country’s nutritional goals. Since NFSA grains may well be going to people, who already have enough via harvest and other means, any further delay in identifying the target population afresh would add to wasteful spending.