Given the 1.7% fall in India’s April-January exports—this means exports grew a mere 0.5% per annum in the six years since Narendra Modi came to power — Union commerce minister Piyush Goyal’s talk over whether the Service Exports Incentive Scheme (SEIS) should be withdrawn sounds counter-intuitive; why reduce incentives when this can also reduce exports? But, given that the government doesn’t have unlimited amounts of money to incentivise exports, it probably does make sense to spend the money where it has the greatest impact. A lot of the service exports that get SEIS benefits today are those made by big firms that will continue to export even without a 2-3% SEIS reimbursement. If, on the other hand as Goyal suggested, this money was spent to boost tourism, this would also generate a lot of jobs.

Similarly, in the case of textiles that are another big area of export opportunity, as the High-Level Advisory Group (HLAG) recommended, apart from implementing the technology upgradation scheme better—so as to improve the capabilities of Indian suppliers—the government must get the top 10 global textiles and clothing firms to set up large plants in India. Once the big producers are here, the exports will automatically take place.

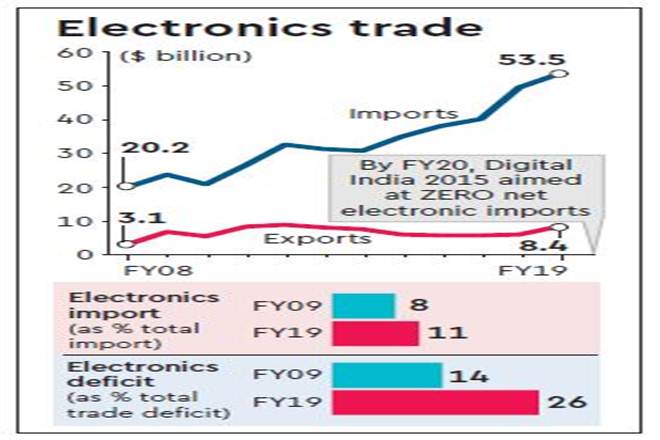

In the case of electronics, where India’s trade deficit is ballooning (see graphic)—at 26% of India’s total trade deficit, electronics is second only to oil—the strategy has to be similar to that for textiles, to attract the biggest global players like Apple and Samsung to manufacture in India; over time, as happened when Suzuki bought Maruti from the government, exports will also start rising on their own. Apple’s exports from China retail at $200 bn, so if this manufacturer is to come to India along with its main component suppliers, logically speaking, India will also become an export hub. The global smartphones export market is around $300 bn—60% of this is done out of China and 10% out of Vietnam—and 75% of this is shared by Apple, Samsung, Huawei, Oppo/Vivo and Xiaomi, so getting these biggies to manufacture in India is critical.

India began talking of wooing firms like Apple and Samsung 6-7 months ago when the then principal secretary to the prime minister asked secretaries to various ministries to draw up a plan to woo big manufacturers in China in the light of the increased US-China trade tensions; these firms were facing the possibility of their exports out of China being slapped with import duties when they were shipped for sale in the US. Despite this, however, no decision got made and, meanwhile, the US and China managed to dial back on the trade war, reducing the urgency for firms to want to exit China. Samsung which had a large part of its production in Vietnam anyway, shut the last Chinese factory during this period; while Samsung also has a large facility in Noida in India, most of its production takes place in Vietnam.

The huge disruption in global trade and manufacturing in China thanks to the coronavirus has, once again, opened up an opportunity for India to try and woo global biggies; it is important to get it right this time. While India’s trade deficit was $133 bn in April-January FY20—it was $136 bn in FY14 and $184 bn in FY19—what is worrying is that the share of electronics in this has been consistently shooting up; it was 14% a decade ago in FY09, 17% just before Modi took oath in mid-2014 and is around 26% right now. In absolute numbers, the electronics deficit shot up from $17 bn in FY09 to $45.1 bn in FY19. Compare this with the zero electronics deficit that Digital India 2015 had projected for FY20. Indeed, while India’s mobile phone exports were a mere $2.7 bn in FY19, the National Policy on Electronics 2019 projected these rising to $110 bn by 2025!

Interestingly, while the electronics deficit had been rising, it remained at around $23 bn in the few years before the Nokia phone factory shut following a dispute with the Indian tax authorities. At that point, smartphones were around 30% of electronics exports and this collapsed after Nokia shut operations despite the fact that, by then, India started its phased manufacturing programme (PMP) for mobile phones. While some will argue that India is better off continuing with its PMP—import duties are hiked to accelerate local production of various components—the continued rise in imports, and the poor export showing makes it clear this doesn’t really help; large exports require genuine manufacturers, not mere assemblers.

A purely export-incentive-driven offering, say, 5% of the value of each phone exported may appear a good way to reduce the cost disadvantage of manufacturing in India as compared to either China or Vietnam, but this may not work as it could well turn out to be WTO-incompatible. In which case, just ensure the likes of Samsung and Apple manufacture more in India, whether by way of greater tax incentives or free land or some other facility is for the government to decide; as the firms scale up and get more efficient, exports will follow. Apart from manufacturing, with India also emerging as a global player in engineering R&D centres—SAP and IBM get 8-10% of their global patents from their centres in India—and firms like Qualcomm, Texas Instruments and Intel already doing some work on chip design here (bit.ly/2HFsc7J), there is also more scope to do value addition in India than in, say, a Vietnam.

Indeed, it was more R&D in India—after Suzuki bought out the government stake in Maruti—and involving Maruti engineers in its global projects that saw, over time, India becoming a small-car exporter. Given India’s sad history with missing several opportunities—when China vacated the lower-end of the textiles and clothing market, it was countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh that took advantage of this—it can’t afford to miss out on the electronics opportunity; more so since Vietnam has already marched ahead by getting most of Samsung’s operations.